We all have a short time on this planet, and some of us are lucky enough to get to work on tools that people use to make music. You can count on your fingers the number of people who had the kind of influence that Don Buchla had on electronic music in the last century. And this week, at age 79, he’s left us.

The reality of instrumental history (electronic or otherwise) is that instruments aren’t simply invented. They are instead best described in clusters of activity around musical practice, even with certain objects at the center.

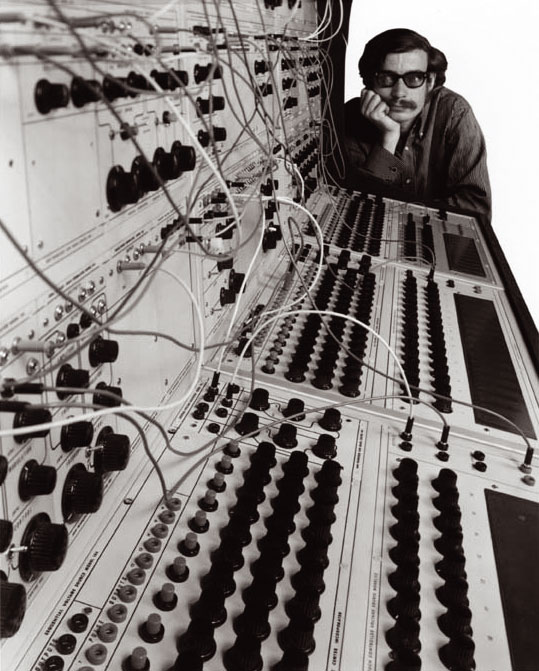

And Buchla’s instruments have been at the center of musical practice since the 1960s, from the 1963 debut of the System 100 modular and in each decade since. They were at the heart of Morton Subotnick’s music, including his legendary Silver Apples of the Moon. They were the soul of Pauline Oliveros’ ground-breaking work at the San Francisco Tape Center, too, and you can still catch Suzanne Ciani making music with them today as she continues to use them to break ground.

Working with composers, Buchla helped dream up many of the ways people design and think about modular synths. In particular, it’s hard to imagine sequencing on synthesizers without Buchla’s contributions on his modular.

Buchla I believe deserves as much credit as Bob Moog for the invention of the notion of modular synthesis in hardware generally – alongside Max Mathews and the team at Bell for the creation of unit generators and modular synthesis in software form. That should never have to be a contest, some Olympic sprint between two inventors. It’s when you realize how the two played off each other’s ideas and the musicians they worked with that you see how powerful that moment in musical history was. Much of the talk West Coast or East Coast synthesis is misleading (further muddled by the fact that many of the supposed Californians were from New York). If anything, it seems as you study the record that it was the coexistence and interchange of Buchla and Moog, composers and musicians, that helped create the nuclear explosion of electronic music.

But it’s not just modulars. Buchla also leaves a rich legacy in performance interfaces, modular and beyond. The Buchla modular itself was from the start conceived as a performance instrument – a radical notion at a time when electronic instruments were largely devices meant to construct sounds for tape, and still a challenge to pull off today. From the touch plates on the first modulars, to his Thunder and Lightning (which have influenced gestural interfaces generally), to marimbas and piano bars, Buchla’s mind was an endless source of ideas about how to play.

But this is why I think it’d be a mistake to look too hard backwards, or to try to sum up who Buchla was in a series of pieces of hardware. It’s important that he was someone who made objects, and made those objects function. But at the risk of stating the obvious, a musical instrument is a physical artifact of ideas about music. Buchla’s real influence is a thread that winds through other hardware and software and musical output in ways that may be impossible to trace.

Over half a century on, we’re not going to invent modular synthesis all over again; that’s done. But we might wonder and marvel at how we may dream up ideas about music that can spread – because there, the viral progress of creativity can still be boundless. Buchla’s legacy, on a scale true of just a handful of pioneers, is that there is endless wondrous sound where was there was none, sounds that otherwise would never have lived.

And with that in mind, class with Don is still in session. Watch:

Synthesist and historian-journalist Mark Vail has an enormous extended interview with Don. (full links, described in German, though you can watch the videos either way)

Alessandro Cortini in duet with Buchla:

Everything Ends Here from Alessandro Cortini on Vimeo.

A video recorded at Berkeley starts out shaky, but is fine once Don starts speaking.

The Guardian has a beautiful and succinct obituary.