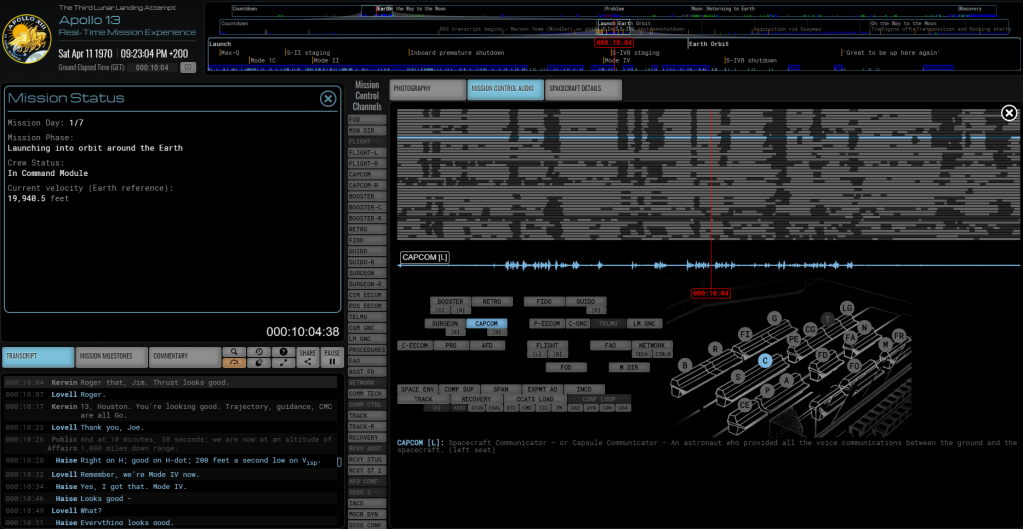

The human experience has been changed by images of space, but the power of sound to tell the story is unfolding in new ways. So here’s a different kind of live stream this weekend – re-broadcast from inside NASA Mission Control, 50 years ago.

https://apolloinrealtime.org/13/

We’re in a weird moment with the the world economy on pause – maybe the exact opposite of the literally rocket-fueled science and tech explosion that drove the United States to run the Apollo project. But it’s perhaps the perfect moment to focus on what really is “essential” about lots of work – how we fit together. History is an important way to do that, because we have the clarity of perspective and hindsight.

If you read the most recent issue of NASA’s History Division newsletter, you get more on the incredible Katherine Johnson – a reminder that a mathematician was as important to the space program as an astronaut (not to mention that this effort was not only male and white). Dr. Johnson has some words that are inspiring for anyone facing new situations (which I guess at the moment is all of us): ” We wrote our own textbook, because there was no other text about space. We just started from what we knew. We had to go back to geometry and figure all of this stuff out,” NASA quotes her as saying.

So a new complete digitization of multichannel audio from inside Mission Control paints a vivid picture. It also reveals (as I’ve said previously, after talking to a couple of them) – astronauts and engineers use listening and sound in order to be aware of their spacecraft.

Government agency plus internal historical newsletter is usually a recipe for utter boredom, but this is anything but dry. Catherine Baldwin from the NASA History Center describes the result in poetic, musical terms:

You can hear the polyphony of voices, slowly adding to the fray, as each member of Mission Control realizes the magnitude of the problem. In real time, you hear the team discuss the problem and offer solutions, one after the other. The stress is palpable, and the strain in their voices is audible. Then, suddenly, you hear the long, anxiety-filled silences before instructions are sent to the astronauts.

That whole newsletter is a fun read:

https://history.nasa.gov/nltrc.pdf

Ben Feist, a historian and software engineer at NASA, has led the restoration effort of Apollo 13’s audio following projects for Apollo 11 and 17, the first and last human lunar missions, respectively. The project is NASA-funded but also the fruits of a lot additional labor by volunteers.

There are 50 channels of audio, for a total of 7500 hours of sound – and, most notably, the rediscovery of big Ampex reel-to-reels containing the fateful explosion in the Service Module’s oxygen tank. Astronauts hearing that sound on the the spacecraft (and Mission Control over their relay) gave the first impression that the crisis was more than a faulty reading or two. But you can also hear a vivid conversation between Mission Control and the astronauts describing vibrations and sound at each stage of the launch – a reminder that this sort of sensory awareness of your vehicle is as important to someone on top of a Saturn V rocket as it is someone figuring out what’s happening in their Ford Taurus on the highway.

Baldwin notes in her article that there are also moments captured from phoning up Vice President Agnew to a guy getting rejected when he asks a lady on a date.

For us sound nerds, though, the whole project is an epic accomplishment of digitization an restoration, as well as a stunning portrait of the importance of sound in telling stories. I had a first-hand childhood connection to this and Apollo 13. The Command Module lived in the science museum in my hometown of Louisville, Kentucky when I grew up. And various extended loops of these very conversations between the spacecraft and ground played in the installation. One unique aspect of sound to me is not that auditory or visual sense is primary over the other – if you listen in on sound, that is, you imagine all the rest. While we struggle now to bombard ourselves with video conferences, that might be worth considering.

Our imagination of space flight is often more influenced by science fiction than reality. I think we all have to resist our idea that space is a combination of long, Stanley-Kubrick-esque silences interspersed with Ligeti, or the gentle hum of the Enterprise. A former ISS commander told me that the space station is loud (particularly the raucous machinery in the older Russian end of the ship – no surprise).

But I do hope that we extend the awareness of the aural in space, space exploration, and technology. I think that chapter in our appreciation is just beginning. Four years ago I got to collaborate with the European Space Agency on this topic; ESA is staying at home, too, so we all get a chance to think about this. And if at the moment there are no DJ booths for us to inhabit, musicians and sound artists have some time now for us to reflect on our other relevance to communication, understanding, and science.

By the way – lest you think disease is a new problem, exposure to rubella forced a last-minute, unprecedented change in flight crews on Apollo 13.

Happy 50th to Apollo 13th – still hailed (rightfully) as a “success” by NASA, as they got the crew back to Earth.