Much about The Black Dog was and remains wrapped in an air of mystery and mischief, so perhaps it’s unsurprising that Ken Downie’s death this week came as an unexpected shock to those outside of his small immediate circle.

Downie is best known for co-founding The Black Dog, a pioneering British electronic trio that included Downie alongside Ed Handley and Andy Turner. While Handley and Turner debuted in 1991 as Plaid while still part of The Black Dog, the former project took center stage after they left The Black Dog and continues to this day.

Cyber-Egyptology and ambient techno

From the start, The Black Dog mashed together ancient history and the future in a kind of cyber-Egyptology. When I spoke to Plaid in 2024, Andy Turner broke it down as such: “I think with the Black Dog stuff, there was an interest in finding out about things. Ken was an Egyptologist – or, he studied as a hobbyist, so he had a lot of knowledge there. When we met him, we were gathering a lot of knowledge from him.”

And see “The Pharoah” [sic], an early music/visual demoscene creation from Ken Downie and a collaborator named John (at the time of this writing, I can’t find more details about the latter):

“The Pharoah” [sic], Amigo demo from Black Dog Productions

During the early years of The Black Dog, there were some clues as to Downie’s particular fixations and contributions. The Black Dog’s pioneering 1993 release, Bytes, (part of Warp’s legendary Artificial Intelligence series) was credited to collective Black Dog Productions, with indications of tracks written by Turner and Handley (as Plaid), Turner solo (as Atypic), Handley solo (as Close Up over and Balil), and Downie solo (as Xeper, I.A.O, and Discordian Popes). In keeping with the Artificial Intelligence aesthetic, Downie’s tracks are particularly moody, with gorgeous melodies and (often downtempo) breakbeats.

I.A.O – “The Clan”, from the Artificial Intelligence compilation and The Black Dog’s first album

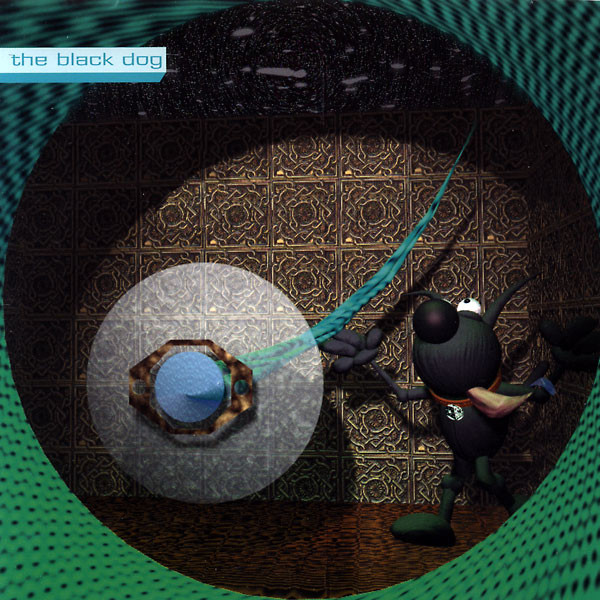

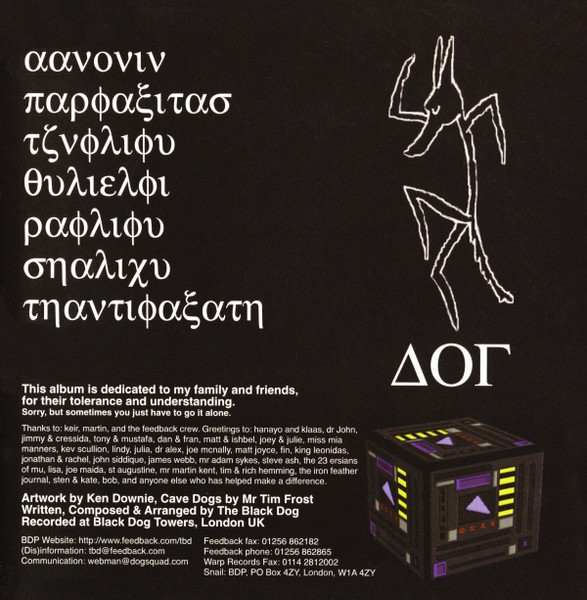

There aren’t specific credits for the trio on their follow-up albums, 1993’s Temple of Transparent Balls (GPR) and 1995’s Spanners (Warp), but the playfulness and cyber-Egyptology aesthetic continues, especially on tracks like the epic pseudo-Middle Eastern “Psil-cosyin” or the gorgeous downtempo of “The Crete that Crete Made”. Plus some not-so-subtle nods on the back cover of Spanners:

And for a personal interlude, I was thrilled to find an original vinyl copy of Temple of Transparent Balls in great playing condition, complete with artwork poster, during a trip to the UK last year

“Sometimes you just have to go it alone”

Following Spanners, Turner and Handley left The Black Dog to focus on Plaid full-time. Downie doubled down on his fascinations with ancient civilizations and magic for Music for Adverts (and Short Films), the sole Black Dog LP to be a Ken Downie solo work.

Aside from a cheeky nod to Brian Eno’s Ambient series (which a later iteration of The Black Dog would revisit with Music for Real Airports), Music for Adverts also winks at the shorter lengths of most of the 26 tracks, many under one minute thirty seconds. Bytes and Spanners had both featured shorter tracks as segues – called “Phil” on Bytes and “Bolt” on Spanners, with “Bolt” continuing to be the standard for many future Black Dog albums.

On Music for Adverts, brevity acts more as a central challenge than as a side concern. An underrated album that’s long overdue for revisiting, its tracks impart a diverse array of emotions and grand ideas in little time.

The Black Dog – “AGW” from Music for Adverts (and Short Films)

It was also during this tender solo period that Downie collaborated in 1998 with Israeli Yemenite-Mizrahi singer Ofra Haza for the beautiful “Babylon (Hammurabi)”. A logical climax of Downie’s passion for the ancient Middle Eastern/Mediterranean world, “Babylon” also features excellent remixes from Jimmy Cauty of the KLF, Scanner, and future International Feel-founder Mark Barrott (as Future Loop Foundation).

Reflecting on the single and Haza’s death in 2000 during a 2005 interview with The Milk Factory (the first outlet I ever wrote for – though this isn’t my interview), Downie shared: “It’s still painful to talk about. I would have loved to work with her again. Or at least have talked to her some more. But she died. Out of everything I’ve ever done, I think the Babylon project is the one thing that I’m most proud of.”

Welcome to the Mental Health Hotline

Aside from Haza, another Black Dog collaborator who passed before more could come out was legendary beat poet and author William S. Burroughs. While no material was released from this correspondence, it was the kernel that grew into another very unique entry from The Black Dog, 2002’s Unsavoury Products.

Working with poet and spoken-word artist Black Sifichi alongside new Black Dog collaborators Steve Ash and Ross Knight, Downie’s tribal and ambient aesthetic is well-matched to the dark humor of Sifichi’s lyrics. A particular favorite of mine is the very Burroughsian “Mental Health Hotline”:

Animated video for “Mental Health Hotline” by The Black Dog & Black Sifichi

Bringing us to Now

To be clear – The Black Dog have released exponentially more material (21 albums, five archival releases, and too many EPs to properly count) in the two decades since their final incarnation solidified in 2005, than in the preceding couple decades. If this section is shorter than the others, it’s not for lack of excellent material to draw from – but rather because of a shift in roles.

Starting with Unsavoury Products, Downie had begun to conceive of The Black Dog as something akin to Andy Warhol’s Factory, where collaborators had roles that weren’t always directly related to writing, performing, or producing music. With 2005’s Silenced, the first artist album credited solely to The Black Dog in nine years, Martin and Richard Dust (the other Dust Brothers, if you will) were full-time members of a new Black Dog trio.

Again, it’s hard to parse a “who did what” scenario here. Going back to the 2005 interview with The Milk Factory, Downie addressed a question about roles in The Black Dog and in new label Dust Science with a curt “I’d prefer not to discuss the inner workings of the band or label.”

In the past couple decades, Martin and Richard’s influence seems to have taken a greater role in The Black Dog. Politics and social statements came more to the fore, alongside passions for South Yorkshire, Brutalism, the more sleep-deprived and darker parts of travel, anthropological looks at conspiracy theories, and most recently a 2025 album inspired by Mark Rothko.

The Black Dog – “Dressed up Ausländer”, from Other, Like Me

If you’re looking for a place to start with this Black Dog mk3, my personal favorites remain Silenced, 2010’s Music For Real Airports, 2013’s Tranklements, and last year’s Other, Like Me. But it’s hard to go wrong with The Black Dog, who have covered significant ground in mood and style and remained remarkably consistent with such a prolific release schedule.

And perhaps it doesn’t matter? It’s telling that the three members of The Black Dog are covered entirely in black clothing and masks on the cover of this year’s Live at the ICA release – much like other long-time electronic collectives such as Tangerine Dream, The Black Dog exists as an idea as much as a concrete set of artists. It can run counter to the instinct of an encyclopedic journalist, but let’s accept the mystery.

Looking at the description of the London gig recorded for Live at the ICA sums things up well: “A sold-out gig in London, in the most perfect setting: a large black box with no lights and an excellent sound system. It could not have been more ideal for us.”