No studio monitors or headphones are entirely flat. Sonarworks Reference calibrate any studio monitors or headphones with any source. Here’s an explanation of how that works and what the results are like – even if you’re not someone who’s considered calibration before.

CDM is partnering with Sonarworks to bring some content on listening with artist features this month, and I wanted to explore specifically what calibration might mean for the independent producer working at home, in studios, and on the go.

That means this isn’t a review and isn’t independent, but I would prefer to leave that to someone with more engineering background anyway. Sam Inglis wrote one at the start of this year for Sound on Sound of the latest version; Adam Kagan reviewed version 3 for Tape Op. (Pro Tools Expert also compared IK Multimedia’s ARC and chose Sonarworks for its UI and systemwide monitoring tools.)

With that out of the way, let’s actually explain what this is for people who might not be familiar with calibration software.

In a way, it’s funny that calibration isn’t part of most music and sound discussions. People working with photos and video and print all expect to calibrate color. Without calibration, no listening environment is really truly neutral and flat. You can adjust a studio to reduce how much it impacts the sound, and you can choose reasonably neutral headphones and studio monitors. But those elements nonetheless color the sound.

I came across Sonarworks Reference partly because a bunch of the engineers and producers I know were already using it – even my mastering engineer.

But as I introduced it to first-time calibration product users, I found they had a lot of questions.

How does calibration work?

First, let’s understand what calibration is. Even studio headphones will color sound – emphasizing certain frequencies, de-emphasizing others. That’s with the sound source right next to your head. Put monitors in a room – even a relatively well-treated studio – and you combine the coloration of the speakers themselves as well as reflections and character of the environment around them.

The idea of calibration is to process the sound to cancel out those modifications. Headphones can use existing calibration data. For studio speakers, you take some measurements. You play a known test signal and record it inside the listening environment, then compare the recording to the original and compensate.

What can I calibrate?

One of the things that sets Sonarworks Reference apart is that it’s flexible enough to deal with both headphones and studio monitors, and works both as a plug-in and a convenient universal driver.

The Systemwide driver works on Mac and Windows with the final output. That means you can listen everywhere – I’ve listened to SoundCloud audio through Systemwide, for instance, which has been useful for checking how the streaming versions of my mixes sound. This driver works seamlessly with Mac and Windows, supporting Core Audio on the Mac and the latest WASAPI / DirectSound Windows support, which is these days perfectly useful and reliable on my Windows 10 machine. I didn’t test Linux but there’s partial plug-in support there and more in the works.

On the Mac and Windows, you select the calibrated output just like you would any other audio interface. Once selected, everything you listen to in iTunes, Rekordbox, your Web browser, and anywhere else will be calibrated.

That works for everyday listening, but in production you often want your DAW to control the audio output. (Choosing the plug-in is essential on Windows for use with ASIO; Systemwide doesn’t yet support ASIO though Sonarworks says that’s coming.) In this case, you just add a plug-in to the master bus and the output will be calibrated. You just have to remember to switch it off when you bounce or export audio, since that output is calibrated for your setup, not anyone else’s.

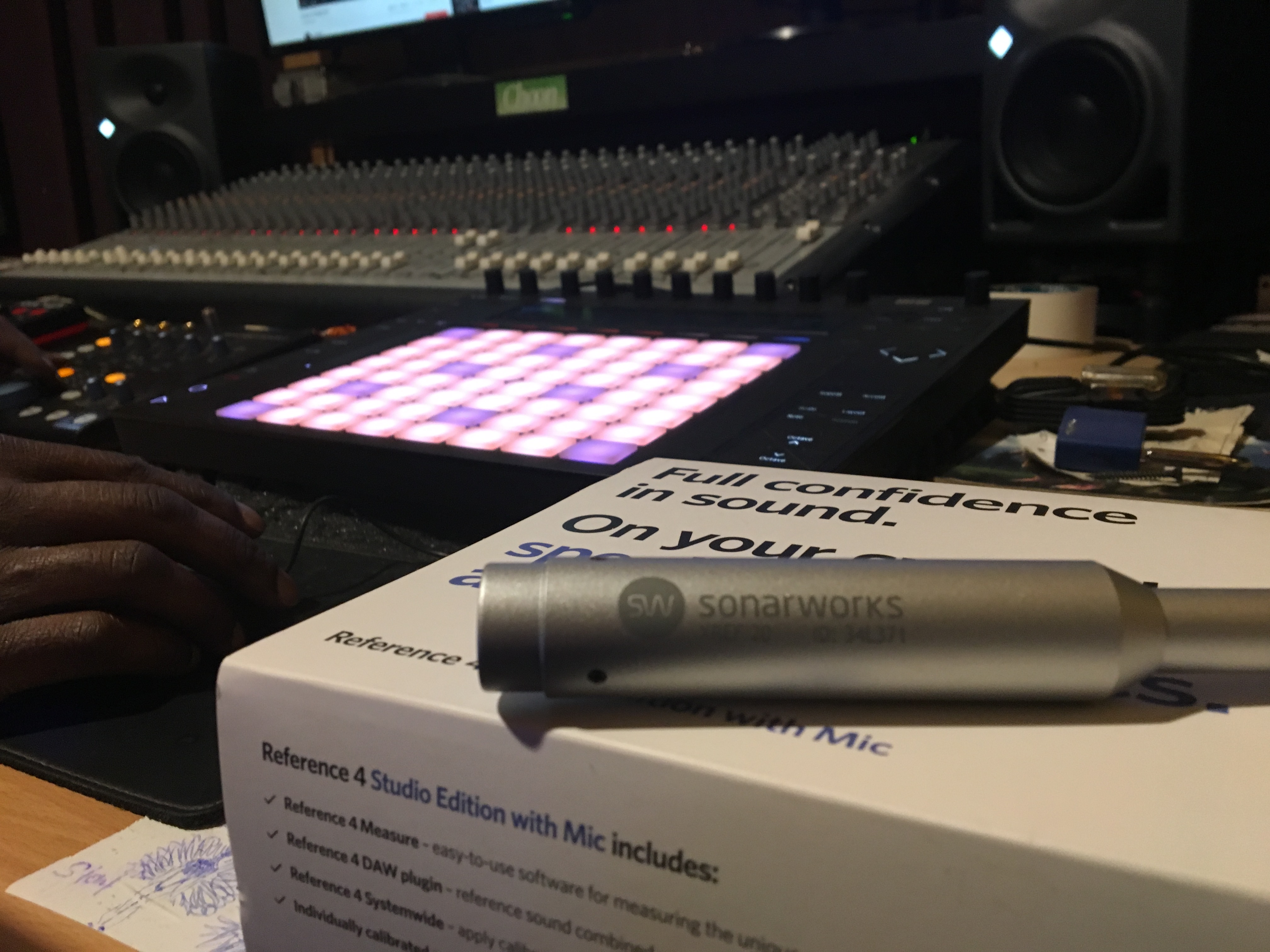

Three pieces of software and a microphone. Sonarworks is a measurement tool, a plug-in and systemwide tool for outputting calibrated sound from any source, and a microphone for measuring.

Do I need a special microphone?

If you’re just calibrating your headphones, you don’t need to do any measurement. But for any other monitoring environment, you’ll need to take a few minutes to record a profile. And so you need a microphone for the job.

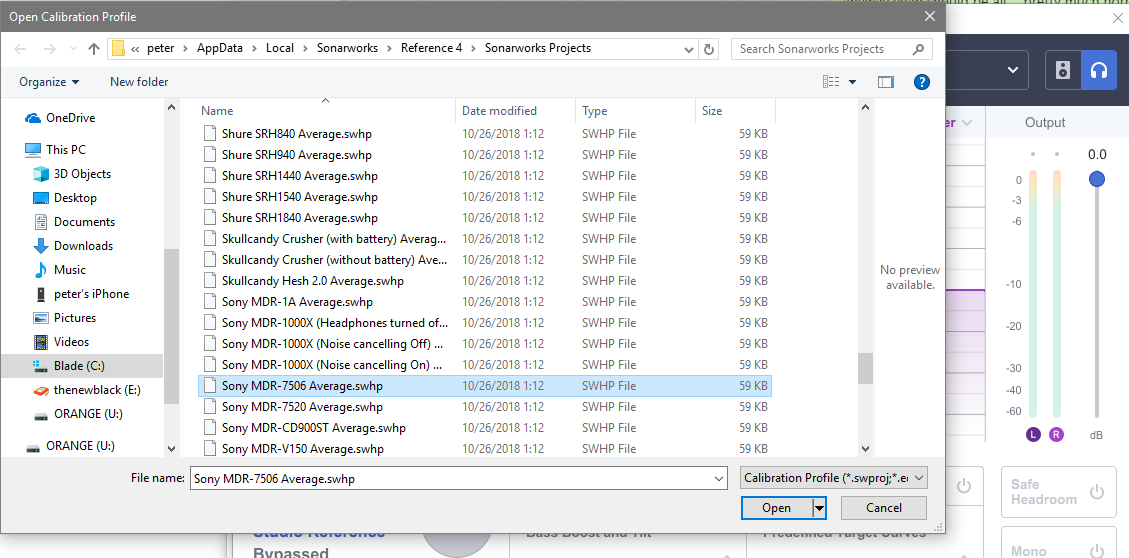

Calibrating your headphones is as simple as choosing the make and model number for most popular models.

Part of the convenience of the Sonarworks package is that it includes a ready-to-use measurement mic, and the software is already pre-configured to work with the calibration. These mics are omnidirectional – since the whole point is to pick up a complete image of the sound. And they’re meant to be especially neutral.

Any microphone whose vendor provides a calibration profile – available in standard text form – can also use the software in a fully calibrated mode. If you have some cheap musician-friendly omni mic, though, those makers usually don’t do anything of the sort in the way a calibration mic maker would.

I think it’s easier to just use these mics, but I don’t have a big mic cabinet. Production Expert did a test of generic omni mics – mics that aren’t specifically for calibration – and got results that approximate the results of the test mic. In short, they’re good enough if you want to try this out, though Production Expert were being pretty specific with which omni mics they tested, and then you don’t get the same level of integration with the calibration software.

Once you’ve got the mics, you can test different environments – so your untreated home studio and a treated studio, for instance. And you wind up with what might be a useful mic in other situations – I’ve been playing with mine to sample reverb environments, like playing and re-recording sound in a tile bathroom, for instance.

What’s the calibration process like?

Let’s actually walk through what happens.

With headphones, this job is easy. You select your pair of headphones – all the major models are covered – and then you’re done. So when I switch from my Sony to my Beyerdynamic, for instance, I can smooth out some of the irregularities of each of those. That’s made it easier to mix on the road.

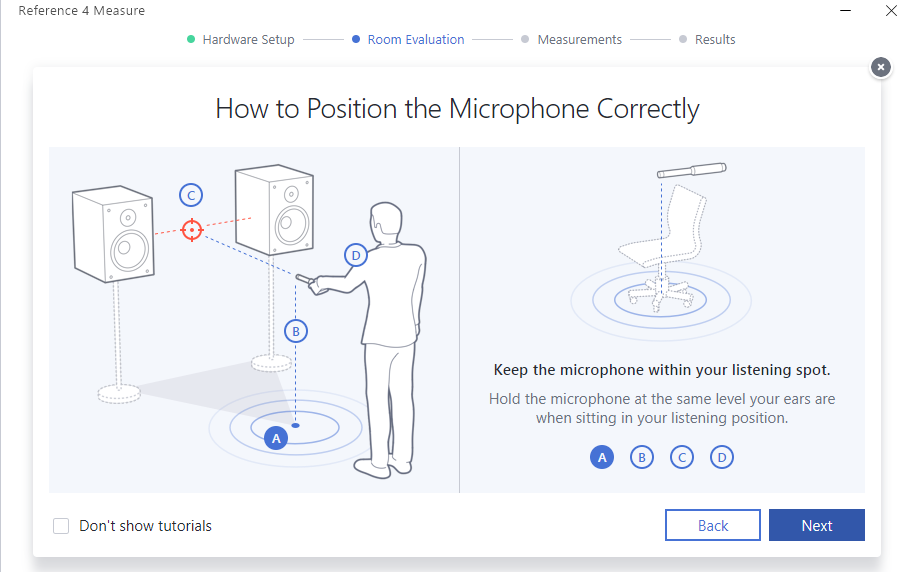

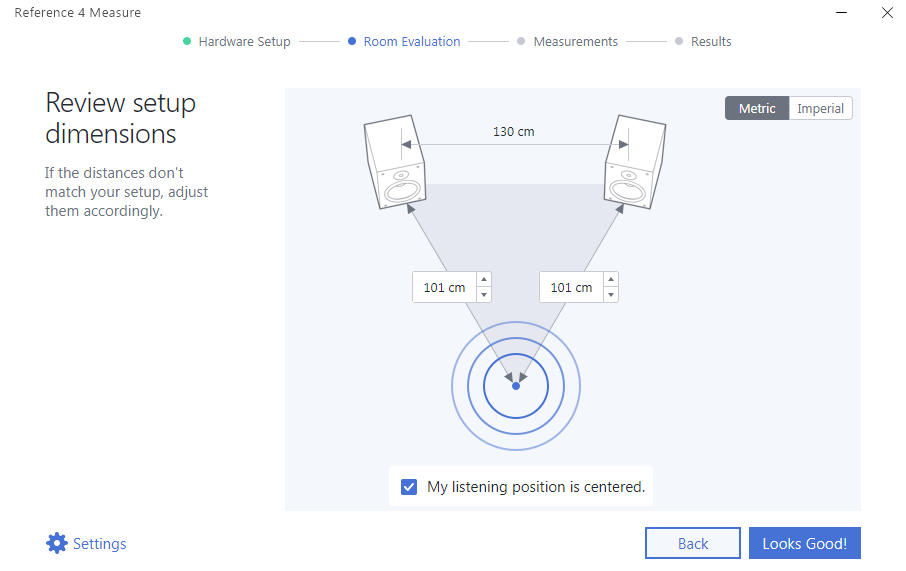

For monitors, you run the Reference 4 Measure tool. Beginners I showed the software got slightly discouraged when they saw the measurement would take 20 minutes but – relax. It’s weirdly kind of fun and actually once you’ve done it once, it’ll probably take you half that to do it again.

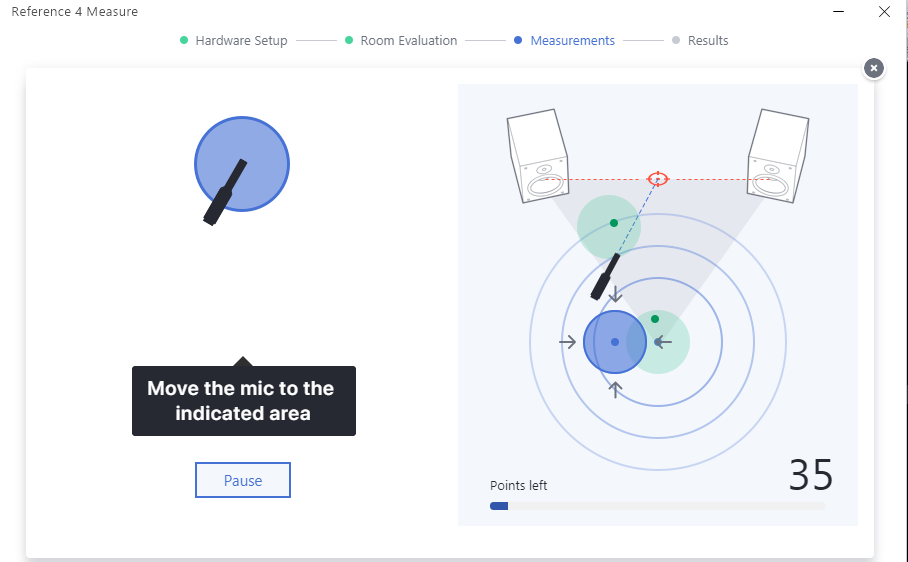

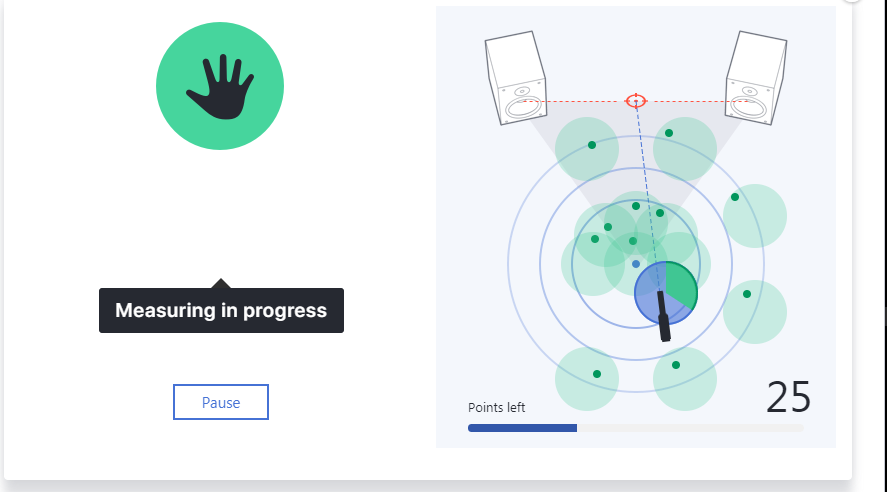

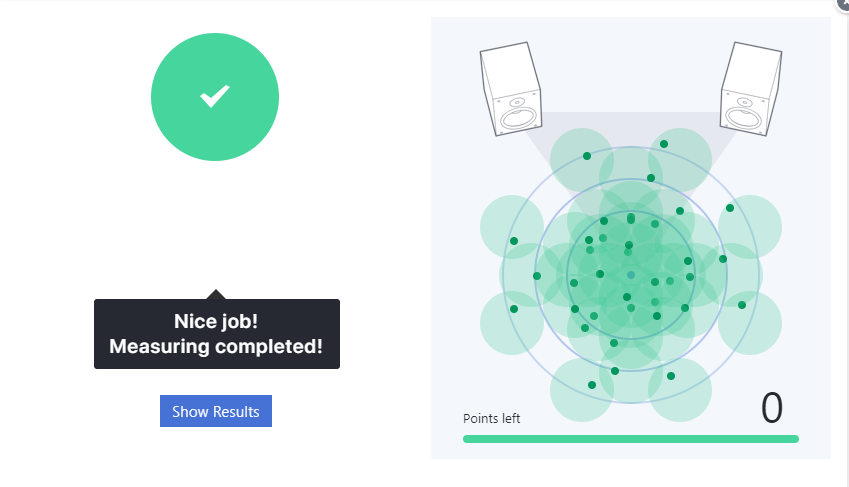

The whole thing feels a bit like a Nintendo Wii game. You start by making a longer measurement at the point where your head would normally be sitting. Then you move around to different targets as the software makes whooping sounds through the speakers. Once you’ve covered the full area, you will have dotted a screen with measurements. Then you’ve got a customized measurement for your studio.

Here’s what it looks like in pictures:

Simulate your head! The Measure tool walks you through exactly how to do this with friendly illustrations. It’s easier than putting together IKEA furniture.

Eventually, you measure the main listening spot in your studio. (And you can see why this might be helpful in studio setup, too.)

Next, you move the mic to each measurement location. There’s interactive visual feedback showing you as you get it in the right position.

Hold the mic steady, and listen as a whooping sound comes out of your speakers and each measurement is completed.

You’ll make your way through a series of these measurements until you’ve dotted the whole screen – a bit like the fingerprint calibration on smartphones.

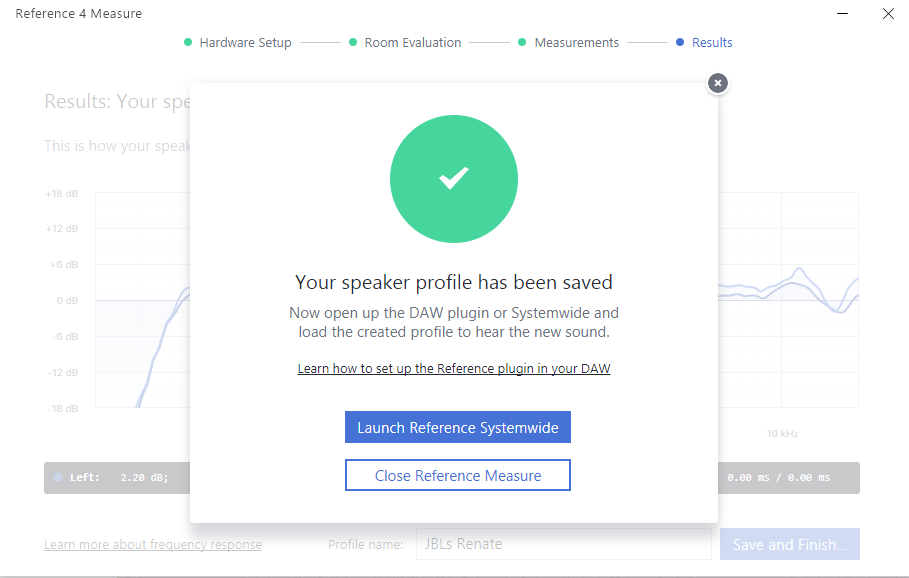

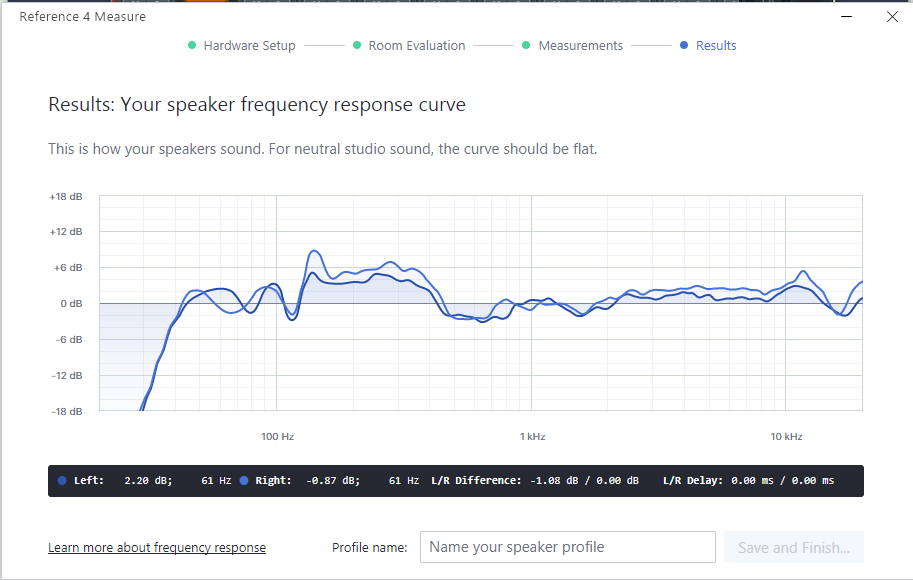

Oh yeah, so my studio monitors aren’t so flat. When you’re done, you’ll see a curve that shows you the irregularities introduced by both your monitors and your room.

Now you’re ready to listen to a cleaner, clearer, more neutral sound – switch your new calibration on, and if all goes to plan, you’ll get much more neutral sound for listening!

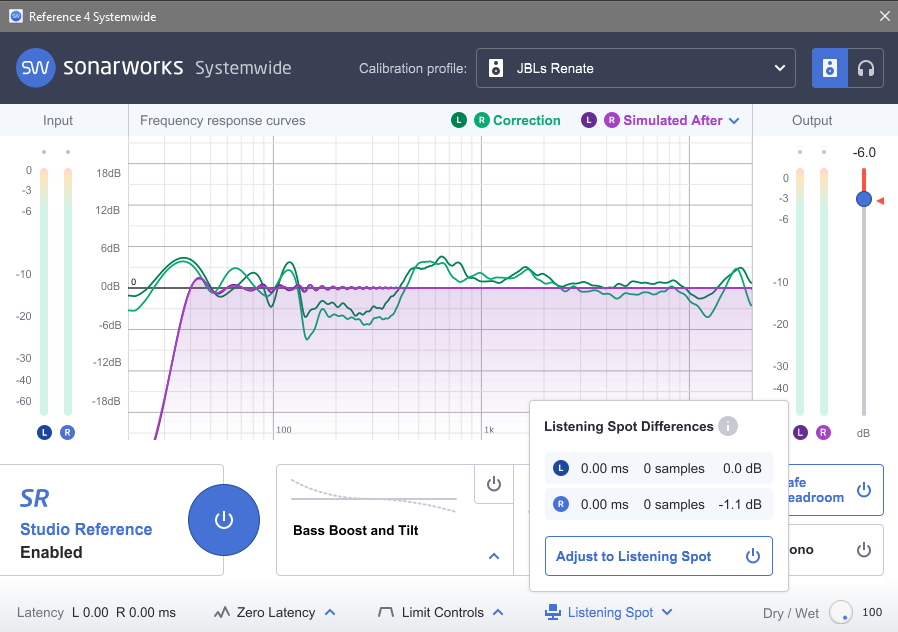

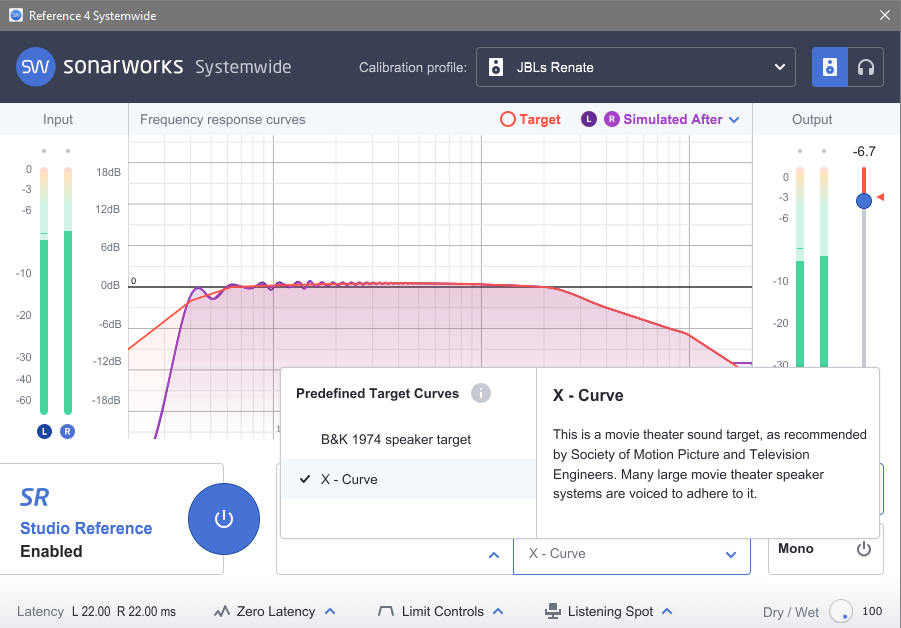

There are other useful features packed into the software, like the ability to apply the curve used by the motion picture industry. (I loved this one – it was like, oh, yeah, that sound!)

It’s also worth noting that Sonarworks have created different calibration types made for real-time usage (great for tracking and improv) and accuracy (great for mixing).

Is all of this useful?

Okay, disclosure statement is at the top, but … my reaction was genuinely holy s***. I thought there would be some subtle impact on the sound. This was more like the feeling – well, as an eyeglass wearer, when my glasses are filthy and I clean them and I can actually see again. Suddenly details of the mix were audible again, and moving between different headphones and listening environments was no longer jarring – like that.

Double blind A/B tests are really important when evaluating the accuracy of these things, but I can at least say, this was a big impact, not a small one. (That is, you’d want to do double blind tests when tasting wine, but this was still more like the difference between wine and beer.)

How you might actually use this: once they adapt to the calibrated results, most people leave the calibrated version on and work from a more neutral environment. Cheap monitors and headphones work a little more like expensive ones; expensive ones work more as intended.

There are other uses cases, too, however. Previously I didn’t feel comfortable taking mixes and working on them on the road, because the headphone results were just too different from the studio ones. With calibration, it’s far easier to move back and forth. (And you can always double-check with the calibration switched off, of course.)

The other advantage of Sonarworks’ software is that it does give you so much feedback as you measure from different locations, and that it produces detailed reports. This means if you’re making some changes to a studio setup and moving things around, it’s valuable not just in adapting to the results but giving you some measurements as you work. (It’s not a measurement suite per se, but you can make it double as one.)

Calibrated listening is very likely the future even for consumers. As computation has gotten cheaper, and as software analysis has gotten smarter, it makes sense that these sort of calibration routines will be applied to giving consumers more reliable sound and in adapting to immersive and 3D listening. For now, they’re great for us as creative people, and it’s nice for us to have them in our working process and not only in the hands of other engineers.

If you’ve got any questions about how this process works as an end user, or other questions for the developers, let us know.

And if you’ve found uses for calibration, we’d love to hear from you.

Sonarworks Reference is available with a free trial:

https://www.sonarworks.com/reference

And some more resources:

Erica Synths our friends on this tool:

Plus you can MIDI map the whole thing to make this easier: