Barker’s Utility is a tour-de-force – economical but sensual, precise compositions that nonetheless sound immediate and personal. And there’s deeper thought behind those sounds, too.

The LP is out since early in September on digital and vinyl with Ostgut Ton, house label at Berghain. Sam continues to helm his long-running series and label Leisure System.

We don’t talk enough about maturity or depth in dance music – let alone about reading lists or footnotes or ideas. But that’s odd, in a way, because having spent a lot of time with the sorts of people who will go to regular 8- (or 26-) hour marathons in nightclubs, I hear a genuine search for a deeper well.

It’s reassuring, then, that Sam Barker is someone willing to reflect openly on the meaning – and sometimes the futility – of dance music. And he can encode those ideas in the music, not just with clever track titles, but in the musical messages themselves.

I certainly feel that in Utility. Talk about a late bloomer – it’s easy to forget this is the “debut LP” from

I spoke to Sam on the afternoon before one of his Leisure System parties at Berghain. We were not so much in the shadow of the infamous power station as basking in sun, as the club that exemplifies darkness was cheerily glowing in the late summer vitamin D. So what better setting than to break loose of some of Berlin techno’s cliches?

It’s interesting to me to know how music making works in regards to time, generally. I wonder if there could be a separate series where you watch people agonize over details, in

I used to have more fun with the details, doing things like very precise edits – cutting things up quite meticulously. But I’m not that patient anymore. And I’m not so into the aesthetic – when something sounds like it took days or months of work, it isn’t so exciting to my ears.

If something that did take a long time can still sound effortless, then that’s different. I think Objekt is a good example of somebody who spends a lot of time on each track and every little detail, but in the end, it sounds very off the cuff. He’s like a magician – every movement is so fluid that you don’t reali

I try and make recordings in a way that I have to do as little editing as possible afterwards. I know myself now, and I just don’t have the time or the patience to be drastically changing something from the original recording, like I might have in the past.

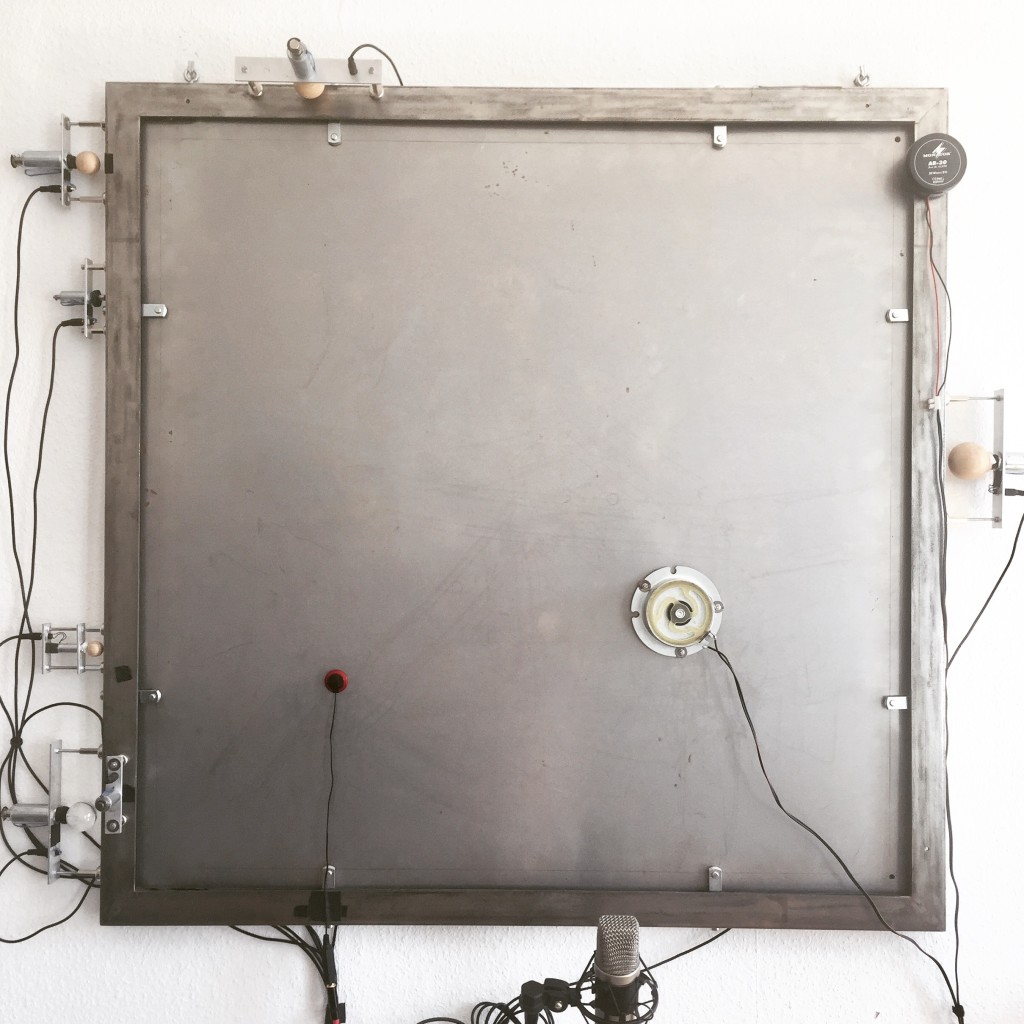

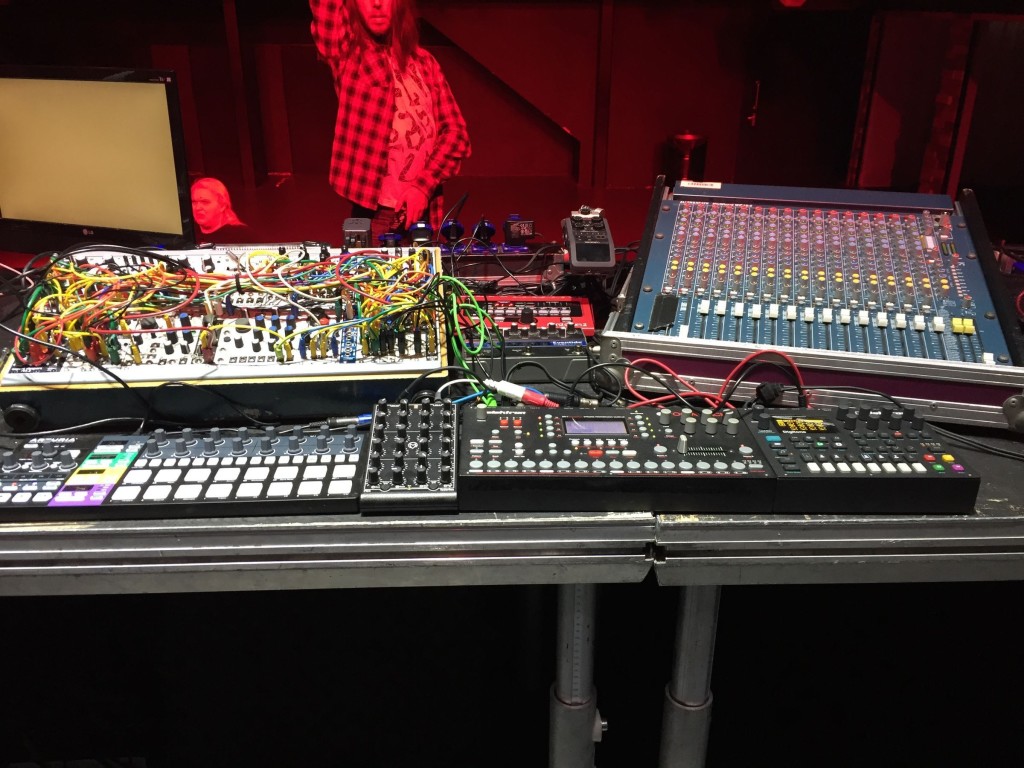

What’s your working setup like; I’ve seen a bit of your instrumentation in the past, but what’s it like now?

I have two

At home, it’s basically my modular system, Elektron Digitone, Octatrack, Nord Drum and some MIDI controls.

That’s a pretty broad palette, though. What I hear – the sound is really focused, and it feels to me like an arrival. It seems like the path you were on from Debiasing [EP] to this release, that now this feels like this clear, mature sound.

I’m glad you think so. [laughs] I definitely feel like I’m answering a lot of questions that have

— downhill in a nice way.

— definitely in a nice way. I’ve spent a long time with the frontier being technology, learning new skills, learning new techniques — training, really. I would set myself challenges that would be to do with learning a process. Getting deeper into certain parts of the modular, or ways of sequencing, using Euclidean pattern generators, building generative Max patches. This would be the inspiration or starting point for a track in the past.

Now, I feel I’m at a point where technically, I don’t really yearn for any new skills. Not to be a technical show off or anything, but I think at some point, you master the techniques you need to make the ideas you’re having materialise. In the end it’s just a craft. The fun of these technical challenges wears off. So it’s like, what’s the new challenge, the new thing to bump my head against?

Right – you have some chops that you’re applying. You’re out of school.

At this point, either music becomes a boring, repetitive task, or you find things outside of the process to inspire you instead.

Was it repetitive in that way?

Working with other people gives a different purpose, but on my own I was struggling to come up with new ideas or finish things. I was here in the studio with the 16-step Cirklon sequencer, and there’s so much potential with that, but it’s like — why do I end up putting this sound in the place you’d expect to hear it, rather than somewhere else?

And so Debiasing was an attempt to understand and get past the biases I had when it came to making music, particularly with rhythmic or percussive formulas.

The main rule of dance music is the kick drum in a way. It’s always there across all forms of dance music. Other things can drop out without much drama -for

It’s a kind of tyranny.

We discussed this before. [see for instance, “Listen to a mix of music that’s techno, but not four on the floor.” -Ed.]

But then I remember, this first live show I heard you play at Saule [in Berghain], there was a patching error, and something accidentally wasn’t patched into the kick. [Leisure System.32, November 2017, when Sam brought back his live set for the first solo in eight years.]

Oh yeah, that was funny.

That was after you’d gone on this tirade about kicks. So you must have been driven by your subconscious to patch that wrong.

[laughs] Well, the set was already kind of without a real kick, just a bass line that had two trigger patterns, one gate for the sustain, and another for a ‘punch’ to the pitch envelope. Basically, a tuned kick that doubled up as a bassline. I was playing and thinking to myself, ‘wow I really programmed a weird set here’, and right at the

But it worked, actually. And people were dancing to that whole set. So whatever you did that you didn’t intend, right? You shifted your intention. It seems like people responded.

It was encouraging for sure. I remember Par Grindvik was behind the stage before I started. And he was like, ‘hey good luck, man.’ I said ‘I’m fucking nervous’ and he tried to reassure me, ‘aw, you shouldn’t be nervous, anyway in the end, just stick a 4/4 kick down and everyone’s happy.’ And I said ‘but… I don’t have a 4/4 kick’. He wished me good luck.

So yeah, what does that mean to you?

The techno formula looks very boring on paper. And objectively, it is boring, but somehow, it works. It has high instrumental value in making people dance. You can rely on it to do the job. I came to the conclusion that this has a lot to do with cognitive biases. There’s a confirmation bias – when it happens, the hi hat comes in, we’re like, yep, see, I expected that. And there’s the illusion of truth effect, where something is repeated so much that it just becomes true. Or the mere-exposure effect, which is a preference for the familiar. Our relationship with music is full of these kinds of cognitive biases.

There’s a book by Abraham Kaplan called The Conduct of Inquiry, which is about how scientists can be more successful in their approach to scientific experimentation. I read it, and in my mind I was replacing the word “science” with “music”. And so many things were just perfectly applicable to this musical problem.

One thing in particular that he calls the law of the instrument – a tendency to rely too much on one methodology to solve problems. He said, ‘give a small boy a hammer, and he will find everything needs a pounding’. I’ve definitely felt like a nail being pounded into the dancefloor before. So the solution might be to use the tools differently, take away the hammer and try something else, perhaps then you stop seeing people as nails. These ideas, from a scientist’s approach to doing research in the lab was a sort of eureka moment.

Do you think if this repetition is about confirming bias, does that influence other thought patterns?

I always think of cue cards – like a TV audience, when somebody holds one up and it says “applause”, and people clap. And it’s like the kick is the cue card that says “dance”, and when it comes in, everybody’s supposed to dance. There’s a behaviorism aspect of dance music that I find a bit pushy, like Skinner’s experiments in the 50s and 60s, where he’s teaching rats to behave in certain ways through manipulating punishment and reward schedules. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operant_conditioning_chamber]

And you feel like that as a DJ.

I think it’s good to be aware of this dynamic. DJ’s as operators of a Skinner box, controlling the punishment and reward schedule… in a way that keeps people on the dance floor as long as possible – ultimately, in the club, drinking. But some of the best parties I’ve had were short and to the point. You would go and see in three hours, like, six

Perhaps this is also a case of styles developing around time restraints – venues in the UK had strict licensing laws keeping opening times short. Anyway I think the length of a night out isn’t an accurate measure of how good it was.

So you’re finding some ways to solve this in your own productions, to break some of these biases – even if you still play longer sets with consecutive kick drums in them. I wonder what you’d call this; it seems like suddenly some of your music is labeled “trance” for some reason.

I don’t mind references to trance. I was never influenced in any special way by trance as a genre. Trance was like a dirty word for me for a long time, so it’s interesting that people hear that. Perhaps I was living in denial of my trance callings this whole time.

If you had to choose a genre label, what would you call it?

I’ve heard a few excellent genre names from people. Minimal bass. Minimal drum. Hard chord. Chris Ssg says big room ambient. Then there’s vegan techno, techno lite..

Lite – ooh, not that one.

Happy hard chord?

Well, there is a strong harmonic element – that was in the Barker/Baumecker stuff too. Andi [Baumecker] likes this, too, I know.

I think there was a phase in techno that was very dry and functional, without anything contentious. I feel like things are changing though. There’s always a lot of unconventional music being made, but I feel people are more curious about it these days, and there’s more support for things that sound different.

Berlin, I mean, there’s some conservatism to the culture here in general?

When I arrived in 2007 it was quite narrow. The tempo was just much lower, and people were very sensitive about things like that. Rhythms diverging from straight 4/4 were really a challenge to play. So with Leisure System, a lot of things that were just part of UK party culture didn’t translate.

Is it any different – Leisure System, tonight, than doing it in the past?

People know what to expect now. It took a few years for people to not be expecting techno. Still we had to find new formulas that worked. In this place [Berghain], the acoustics can be quite restrictive, because it’s very loose in there, and part of the appeal is this cathedral effect that you get on the music that you play. It enhances some things, and it has the opposite effect on other things.

Right, Berghain has impact on the music.

It’s got this classic shoe box concert hall shape, which gives it a pretty nice even acoustic response, but it’s just a very long and very prominent reverb. If you you’re doing a sound check in there and you just play a click through it, it hangs in the air a long time. You have to work with it. And it’s kind of glorious in a way, and it taps into very deep historical response to acoustics. David Byrne talks about how caves were spiritual places for early humans, because they represented shelter and safety, and this feeling was then exploited in how churches and cathedrals were designed.. So this response to reverb is deeply programmed into our DNA.

Yeah, when you hear this reverberation, you hear the room speak back to the music – and there’s something kind of spiritual about that.

There is a call and response in the space. And sometimes great music that I really love falls totally flat in there, and sounds like a mess.

..then I suppose now you hear some producers trying to replicate that sound – knowingly or unknowingly in the track – which of course then won’t work, if you play that track in the club.

Yeah, like layering reverb on reverb..

But it has a sound, right? It’s not neutral – this room says something.

It definitely has an opinion. It can restrict the complexity and

https://sambarker.bandcamp.com/album/debiasing

http://ostgut.de/label/record/243

http://ostgut.de/booking/artist/barker

Cover photo, top: Elena Panouli. Courtesy Ostgut Ton.

Let’s close with Sam’s recent mix for FACT:

Previously: