First seen as a Moogfest workshop, the Subharmonicon is coming to the rest of us. And it’s a chance to explore timbre, rhythm, and pattern in new ways, via knobs or patching. We go deep with its creator into the ideas that inspired it.

And yeah, that will take us beyond just chatting about ladder filters. Strap in for radical ideas about how a 4-step sequencer can be organic (seriously), the kind of strange instrument invention you’d want in a 1932 program shared with Xanadu, plus the hottest musical theory ideas ever to come out of Kharkiv.

Wait. No.

This sounds entirely esoteric. But I’ve had the new Subharmonicon for a few weeks now, and what’s magical about it is, esoteric patterns of rhythm and sound are suddenly accessible, and musical, for anyone. Straight out of the box, the package is complete and friendly. It’s got a manual you’d actually want to read, for fun. And it can go from tripped-out ambience and loops to firey electric dance music, really, even in the same patch.

Let’s get in the mood. Moog have launched a wonderful, far-out audiovisual delight in the form of a short film by Suzanne Ciani and Scott Kiernan.

Electronic music pioneer Suzanne Ciani and multidisciplinary visual artist Scott Kiernan invite you to reimagine conventional ideas of music, sound, and expression through a delicate balance of mystery and order in this experimental piece composed entirely with the new Moog Subharmonicon synthesizer and analog video synthesis techniques. The film’s visuals and narration offer a deeper understanding of the instrument, drawing inspiration from the language and illustrations found in Bob Moog’s old copy of Joseph Schillinger’s book “The Mathematical Basis of the Arts.” Engage your imagination as the rhythmic ping-ponging of Ciani’s score meets Kiernan’s depiction of the evolving shapes, forms, and textures Subharmonicon’s sound creates. Now available worldwide, the Moog Subharmonicon is an intensely creative semi-modular analog polyrhythmic synthesizer. As with Mother-32 and DFAM, Subharmonicon conforms to the 60HP Eurorack format; features aluminum rails, finished wood side pieces, and an extensive patchbay; and can perform as a standalone electronic instrument.

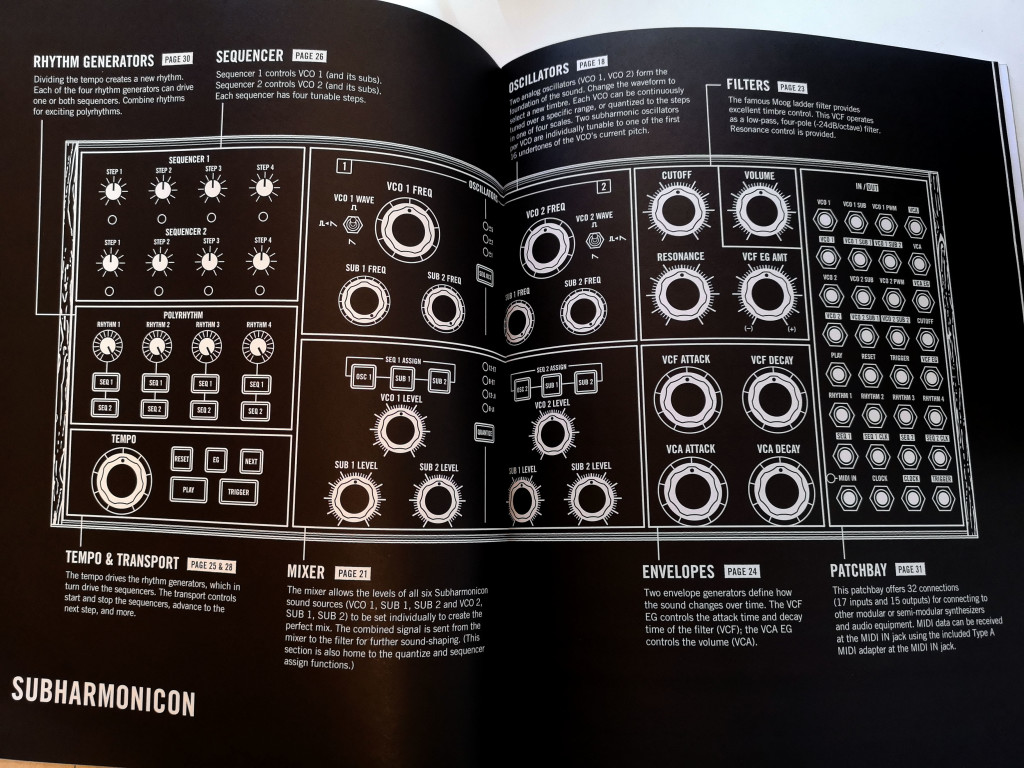

The hardware itself, all packed into the same form factor as the DFAM drum synth and Mother-32 semi-modular:

Sound

2 VCOs, plus (the subharmonic bit):

Four subharmonic oscillators

Pattern

2x 4-step sequencers

4x rhythm generators

Patch

— and a healthy patch bay with 32 patch points for creating patches onboard, connecting to outboard analog gear and Eurorack, or all of the above

The titular subharmonic bit is what makes this so delicious. So you know about overtones – this divides the frequency by integers, something only practical with something like controlled voltages. It’s true electronic music – not synthesizing something you’ve heard before, but really immersing yourself in voltage and waves.

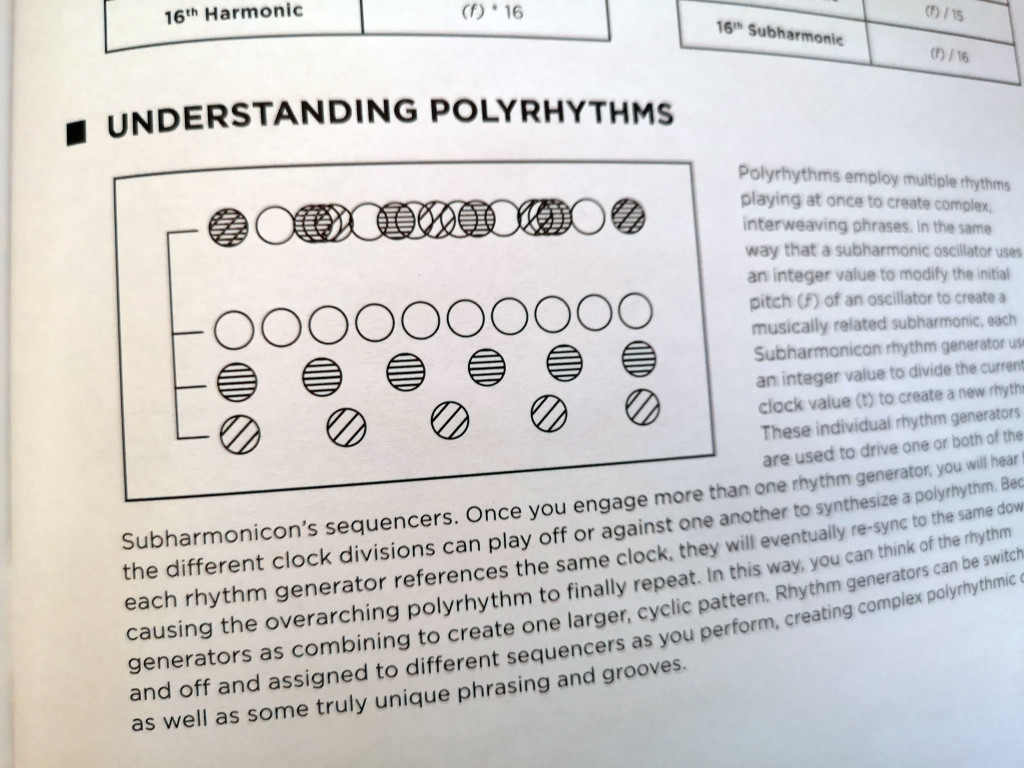

If it were just about subharmonics and timbre, this might feel a bit limiting. But the Subharmonicon is also uniquely equipped as a pattern generator, as it borrows from the related application of this notion for making polyrhythms, inspired by Lev Termen’s Rhythmicon. (That’ll be a lesser-known contraption from the guy who gave you the Theremin.) The Subharmonicon is both way more compact and way more flexible than those inventions, though. At first, the deceptively simple 8 knobs seem like they’ll be limiting. But by assigning different rhythmic relationships between steps, and changing how you assign the step sequencer to control the frequency, you can get really organic patterns quickly.

The combination of the two is essential – the shifting patterns of the polyrhythmic step sequencers with the timbral combinations of the oscillators is a peanut-butter-and-jelly kind of pairing.

I’ll go a little more into the interface and the kinds of sounds you can get as I finish off a little EP made of sounds from jams in my first encounters.

The full package works standalone (power’s in the box). You can use an included adapter to connect the 3.5mm jack to MIDI – and you can sync with MIDI clock, with gear or a computer. And you can patch into other analog/modular gear, including the Mother-32 and DFAM.

Moog just has a winning form factor with these boxes. They’re small enough to just keep around you at all times, focused enough that you concentrate on really playing rather than feeling like you’re programming, but still with ample tweaking and patching that it’s never claustrophobic. And with the Subharmonicon, you get something that I think really can’t be replaced with anything else.

If you’ve seen the original Subharmonicon, this is related to that, but with a lot of usability enhancements, tuning quantization additions, more assignable and playable sequences, a better layout, and features like MIDI. Plus it’s far cheaper than buying one of the ultra-rare original kits.

Price: US$699 street, shipping worldwide now

[US$849 list (EUR849 RRP)]

I have no doubt that a new Moog box will appeal to Moog fans, but if you’ve waited to add some Moog flavor to your rig, this will be the one that’s tough to resist. The Subharmonicon feels both uniquely Moog-like and able to morph into something else. It’s got the best bits of a Moog Voyager, and a reasonable-enough set of oscillation, modulation, and filters, all patchable, to feel like a good starter kit of sound building blocks – or the beginning of a modular. But then it also has the unique possibility of shaping sounds with subharmonics and producing polyrhythms.

And now, at a time when you might want to really take some time and get lost in an instrument, not just get more of the same – this thing is perfect.

Product: https://www.moogmusic.com/products/subharmonicon

Plus some history:

The Historical Inspiration Behind Subharmonicon

With so many ideas here, it made sense to go to the source – Steve Dunnington, who led its design from the start.

Interview behind the scenes

Peter: How did this project’s seed first get planted – and what’s this got to do with the Rhythmicon and so on?

Steve: During the development of the DFAM for Moogfest 2017, I did some research on analog metallic percussion synthesis. I was exploring passing a VCO through a pair of Divide by N circuits into XOR circuits to simulate multiple square wave oscillators at clangorous intervals. It was interesting, but what really stood out was the subharmonic based chords you could get, and how when you reduced the frequency of the VCOs, the subharmonics were generating polyrhythms.

The result of this research didn’t make it into the DFAM, but it was percolating in the ol’ noggin for a year or so until it was time for us to develop a 2018 Moogfest Engineering Workshop synthesizer. For this project, I revisited the experiment from the year before and ideas started bubbling up. What if we combined a subharmonic rhythm generator with subharmonic sound generation, a la the Mixtur-Trautonium? The design sort of burst out of that idea. The beauty was that a lot of the circuits were pretty much the same for both the rhythm generation and the VCO’s subharmonic generation and that it married two fascinating concepts from the early days of electronic music.

I have been aware of the Rhythmicon since I was in college, and had even messed with Max patches — just Max on a Mac Plus, pre Max/MSP, which dates me perhaps — to simulate the instrument. If you don’t know it, in its most basic form it is both a “polyphonic” tone generator and polyrhythm generator based on the simple ratios of the harmonic series. I’ve always loved the concept of exploring ratios and how they relate to harmony and rhythm in an intertwined sort of way.

What was your job title on this project who did you work with on the team? I know this is not your first time round at Moog, of course.

My official job title at the time was “product development specialist” or something like that – I’m not big into job titles – now it’s “hardware team leader”.

We have a small team of hardware engineers and I am charged with keeping them on the straight and narrow.☺ In early 2018, I was responsible for delivering the original Subharmonicon design to the Moogfest workshop. After the workshop, the synthesizer design generated a surprising and persistent amount of buzz, including a petition for us to release it. So we put our heads together to address some of the things that folks wished the product had, like MIDI, and made some other design tweaks to see if we could make a compelling refresh of the design that would make everybody happy, encourage creativity, and stay within budget.

The original version was all analog, so to introduce MIDI we added an MCU [microcontroller], which allowed consolidating the sequencer into the MCU as well. To get the new version realized into hardware, I worked with Cyril Lance picking out an MCU and solidifying an architecture. Once we had that, our firmware team leader, Sylvan Williams, worked ungodly long hours to crank out the features required to turn a collection of parts on a PCB into something truly musical. Our mechanical engineer Steven Hobbs had the job of making something that looked pretty – as a rendering looks pretty – in real life.

And there are a lot of other folks who pushed this project forward. It’s really a team effort that brings these instruments to life.

Compositionally, talk to us a little bit about this sequencer approach. You come to it at first and it seems like a pretty obvious step sequencer. But then you get into this POLYRHYTHM notion. How do you hope people will explore that; what kinds of things have you discovered?

There are a couple things I hope people explore: One is that in music, especially with analog synths, a clock does not have to be just a regular clock. Analog sequencers store a list of CVs that can be pitches, timbres, dynamics, whatever, but it doesn’t have to be output at a fixed tempo or rate. A looped step sequencer can be interesting, but it can be more interesting if there is some variation causing the pattern to move or rotate. In the case of the Subharmonicon it can make four steps seem like a much longer pattern.

Another is the idea of one pattern rotating in relation to another – You can set one sequencer to be 4x slower than another, say by having one sequencer at a divide-by-2 rhythm and the other sequencer at a divide-by-8 rhythm. That can be a nice minimal riff, but it is very repetitious. If you add a divide-by-15 rhythm into one sequencer and a divide-by-13 into the other, the patterns rotate in a really nice way.

On the Rhythmicon topic – this is fairly simplified from that concept, yeah? Was the idea to make this more accessible, more compact, or how would you relate them?

I find the connection with the Rhythmicon is through generating polyrhythms from simple harmonic ratios. Harmonics are all integer multiples of a fundamental 1x, 2x, 3x, 4x, etc. (Note the Subharmonics are integer divisions x/1,x/2x/3,x/4 etc.)

The Rhythmicon is not a really playable musical instrument that I can tell – it seems like it was designed for exploring the combination of these harmonic relationships in pitch and timbre. The Subharmonicon really invites you to play with these things, which is why there are only 4 rhythms, but each can be varied at arbitrary times during music making, either with panel control or with a CV.

How about the relationship of pitch and rhythm on this instrument, again with historical contexts in mind?

Interestingly, one of the folks involved with the development of the Rhythmicon, other than Leon Theremin and Henry Cowell was Joseph Schillinger. A music theorist and composer, he was the author of The Mathematical Basis for the Arts and spent much of his career developing a system of musical analysis and composition.

The Subharmonicon was inspired by some of the ideas and musical concepts of Schillinger, such as the idea that by taking a set of pitches and superimposing them on a set of rhythms with a different length will generate rotating musical motives. In my experience there is a sense of “resolution” as the pattern rotates and becomes familiar again, similar to the feeling of resolution one gets from the old dominant-to-tonic Western harmonic resolution.

The fit and finish are familiar, but let’s talk inside. What’s the lineage of Subharmonicon to the other stuff in the Moog range as far as sound-making guts? There’s a certain amount of reuse or adaptation, yes?

Sure, all analog design involves reuse of familiar circuits and topologies. The actual synthesis topology is a quite simple subtractive topology: VCOs>VCF>VCA. The VCOs are a new version of the sawtooth relaxation oscillator that Bob developed for the Voyager, which was essentially a modern (circa 2000) take on the Minimoog VCO. The VCF is a 24dB/oct Moog ladder [filter], and the VCA has a direct lineage back to the Voyager as well. It’s great-sounding stuff!

Another aspect of the lineage is that when combining with the Mother-32 and the DFAM, you begin to have an ensemble of instruments where each do things in their own spaces that are complementary.

Ladder filter, of course, not sure there’s more to be said about that. But how about these sub oscillators, in particular? That seems like where this instrument can get a bit gnarlier and less nice, in a good way.

The subharmonics are essentially a voltage-controlled divide by N circuit (those things have been around for some time). They also have waveshaping that turns the pulses from the divide by N circuit and converts them to a sawtooth wave or a pulse wave using circuits similar to those in the VCOs.

How does a product like this evolve from initial conception to finished product? Were any changes incorporated after the Moogfest lab? (Well, obviously to change it to a finished product rather than kit, but in service of that or outside of it?)

The first step was realizing that we had a compelling enough concept. Then we started figuring out what would fit on a panel in the Mother-32 form factor – you can’t keep adding features to a space-constrained form factor! Once the features were envisioned, circuit design began for the Moogfest Engineering workshop. Once that seemed sound enough, a prototype layout was done, mistakes and issues were identified and corrected, and a second revision was produced to verify the design. At that point it was time to release to Moogfest, fortunately, everything worked well at that point. Then there was all the effort associated with the workshop itself, which has been quite a journey over the years.

After the workshop was complete and people were asking us to release it, we got feedback from folks who had been a part of the workshop and found there were ways to improve and features that would be helpful to add. Some of the new features include MIDI, a new way to assign the Subharmonic Rhythms as clocks to the sequencers, and the ability to select a range of sequencer modulation as well as a quantized scale. I was happy we included the use of a Just Intonation (ratio based tuning) scale for quantizing – there are some neat timbres you can get with that feature and chords from the subharmonics.

Then came the work of seeing the feasibility of those changes and looking at the budget of the project to see if it could make sense as a product in terms of cost. Following that came the process of re-imagining the panel layout to accommodate the new features, and the development of new hardware to support those features. Once we had prototypes of new hardware, firmware design started. There was a ton of beta testing and firmware revisions along the way. And we developed a production process to get them built on the floor in the factory here in Asheville.

Of course, those of us who weren’t at Moogfest don’t get to put this together – though the out-of-box experience is nice enough, and it’s great to make sound right away! But what was that workshop experience like?

The folks who come to that workshop range from people who have come to every workshop we’ve offered to those who are first-timers, even at soldering. With that breadth of skills to work with, the experience is very focused on first building the thing, and then understanding and learning about the thing.

As I mentioned above we ask feedback from folks regarding their experience at the workshop and the feedback ranges from “get a better PA for the folks at the back of the class to hear you” to “It should have feature XYZ to make it better.” In the case of this product, the demand was compelling enough to have that feedback inform the commercialized design. As a result, the workshop Subharmonicon version is a little wilder and more out there than the commercialized version, as it is the first version of a very unique instrument.

I personally love to work with this already in fairly self-contained form. But how do you also anticipate use with Eurorack (and other Moog gear)? Does that inform the choices about what goes on that patch bay – that is, to imagine both the internal and external routing?

One of the goals for this instrument was to be able to have it presented as an instrument but also to use the sound engine and sequencers separately. This means you can use the Clocks to drive other sequencers, you can use the sequencers to sequence other modules, and you can use the VCOs and subharmonics completely independently as sound sources if you like. The functions are not 100% modular, but modular enough to offer compelling opportunities for experimentation.

I am a big fan of using the Subharmonicon with a DFAM, as the DFAM’s simple analog sequencer can be varied with different clock patterns applied to the trigger and clock inputs. The possibilities approach being endless — the trick is focusing on the things that are musically compelling to you.

Want to talk to us at all about the patches that were included – what decided the ones that made it to cards, or what sort of personality you put into those? (or who made them?)

The patches were the work of the great Max Ravitz and the great Lisa Bella Donna, transcribed to the nice cards included in the box by our very talented graphic design duo. It’s a concept we started with the DFAM, and is quite effective for giving a tour of an instrument for first-time users. We are honored to work with Max and Lisa – they bring such terrific creativity and musicality to the table!

There’s also this gorgeous out-of-box experience, including documentation and the whole package. How does that figure into the design process? It seems like something a lot of our industry talks about but often doesn’t do; who works on this for Moog?

One of our mantras is that when you get a Moog product, it’s special, like opening a Christmas present. All of our design work is done in house by our marketing and design folks who really focus on ways to make that experience joyful and fun.

Did your approach to this box change relative to your past work at Moog, or how would you say you’ve evolved to get to here?

That’s tough to answer. The whole thing’s been a fun and crazy journey with some amazing people – the guiding principle is we always strive to get better and better at designing interesting and great sounding tools for music making. The work is never done! It’s such a pleasure to see what people do with our instruments – it drives us forward, inspires our imaginations, and feeds our souls!

Thanks, Steve!

And to all of you synthesists abroad and the team at Moog (not to mention my Russian friends who are enthusiasts of the Rhythmicon), look forward to seeing you in person soon.

Meanwhile, send music – and patches.

More:

Hainbach has a good walkthrough. He has a good point about the use of a tunable bandpass filter instead of a lowpass filter, and it does seem that Trautonium history or not, it’d be a logical pairing with the Subharmonicon. But – since this thing is patchable, you could use some outboard filter bank, which is exactly what he does.

Basically, this is still a Moog voice – it’s actually the more conservative element of this box, but it becomes interesting with these subharmonics and sequencer. This is where you really hear a Moog instrument rather than a Trautonium.

And here’s what happens when the Subharmonicon meets its siblings: