He’s been a vocalist (as a founding member of Cabaret Voltaire), a lyricist, a vocalist. But if you know the incredible Mal from his past, you don’t want to miss his latest, either – the groove is alive on the wonky disco Tick Tick Tick, ““cowbell on every track, and entirely no reverb.” David Abravanel shares words with the wordsmith and frontman.

words: DAVID ABRAVANEL

Some vocalists are really just… cool. Stephen Mallinder is just fucking cool. I had to start it this way – the man dunks all day on Joe Camel and James Dean when it comes to, well, general aura. In Cabaret Voltaire, Mallinder delivered lyrics that could waver between poignance and poetic stream-of-consciousness, always teetering on an improbable edge between passing through your ears and delivering some seriously important observations. Sometimes I still don’t know which is which – but I’ll always perk up when I hear him breathe out about fascinations. It doesn’t hurt that Mallinder started as a bass player, leading naturally to vocal delivery that fits deep in the pocket, even with the Cabs’ often left-field electronic explorations.

That cool comes additionally from full-throated embrace of funk. It’s something that became far too rare in the 80s, 90s, and 00s, as industrial gave way to industrial metal and finally the kind of mall goth and nu-metal that might have been fun (we’ve since reached the 20-years’-post period where Zoomers genuinely love Orgy again) — but rarely funky. Cabaret Voltaire wrote a song called “James Brown”, and damn, if they didn’t earn that more than most other industrial or synth-pop acts.

Over the years, Mallinder (or Mal) has worn many hats, from Cabaret Voltaire to leading a sound art program at the University of Brighton to current projects Creep Show (with Benge, John Grant of The Czars, and Phill Winter of Tunng) and Wrangler (a trio of Mal, Benge, and Winter).

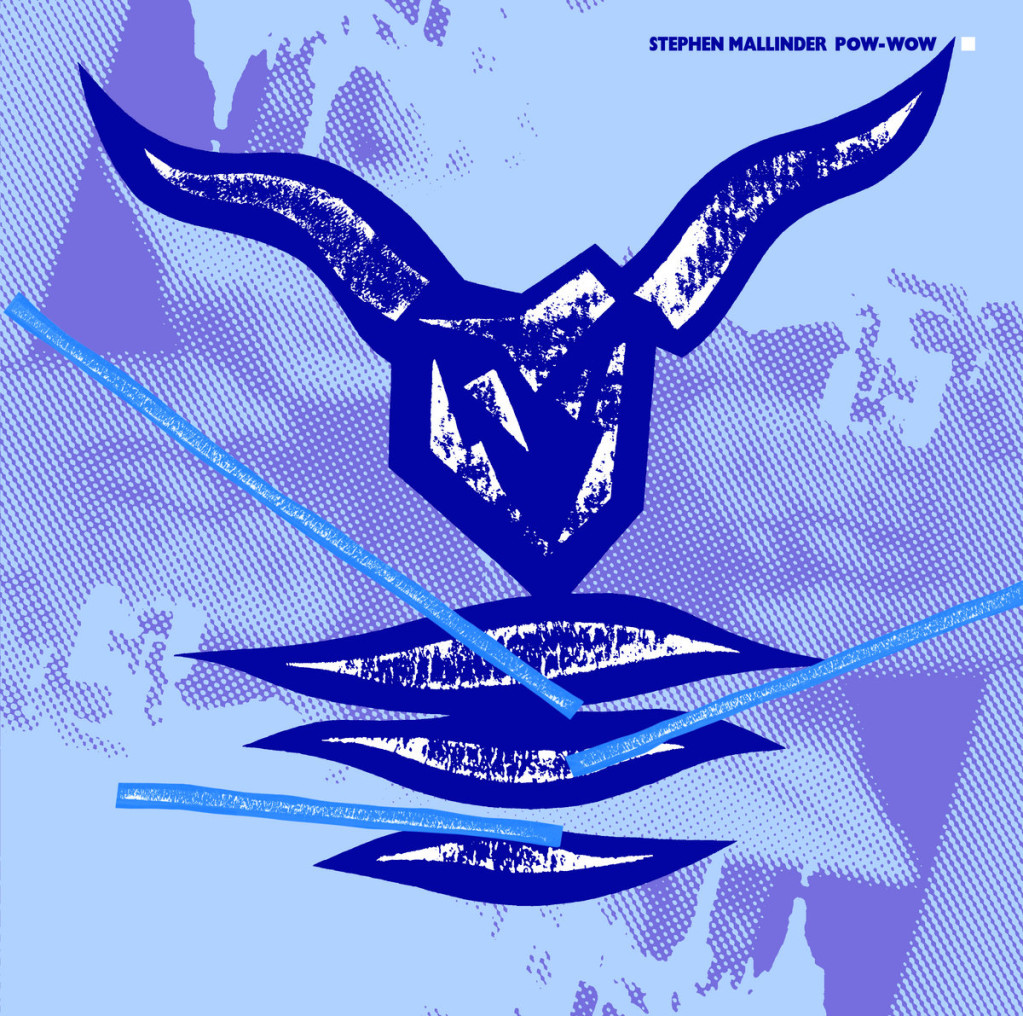

With so many projects, it was a chasmic gap of 37 years from Mal’s first solo album under his own name (1982’s Pow Wow, reissued in 2020) and 2019’s Um Dada. His latest solo album, Tick Tick Tick, arrived earlier this year, a comparatively scant three years later. I sat down with Mal for a great discussion about the plasticity of words, electronic instruments, and working from the influence of so many decades and different projects.

CDM: Your first solo album, Pow Wow, came out in 1982. Then a few decades passed before Um Dada in 2019. Now it’s been only a few years and we’ve got Tick Tick Tick. What brought to back to doing solo albums?

Stephen: I think it was that I’d done so many things under different names, and it’s quite nice to just be you. There was no real deep thing in it, but using my own name did allow me to connect past and present. I’ve done so much stuff other than the Cabs, you know — with Ku-Ling Bros., Sassi & Loco, Rube!, Creep Show, Wrangler…

But then all of the sudden, you think, maybe I’m excluding myself from my own sort of story a little bit, my personality. So I thought, if I do this in my name, then it can reflect back onto those other things that I did – it’s a way of bouncing back to the other things I’ve done. And obviously in all that time, we did so much Cabs stuff as well.

That was also the reason why there was that hiatus, in the sense that when I did Pow Wow, it was what I wanted to do and I had a bit of time. But then quite quickly after that, Rich and I, that became quite a big thing and we signed to Virgin. So really, there wasn’t time to do much of the solo stuff. For both Richard and myself, everything was channeled into Cabaret Voltaire, right through into the 90s when we stopped.

For how long have you been in academia?

Not that long – I’ve always done music as a kind of mainstay. I was living in Australia, and I started writing my PhD thesis there, so that probably goes back about 15 or 16 years. I’ve kind of taught and done stuff part time as well. I enjoy it, because I enjoy writing, and I enjoy that side. And you find that it’s compatible with working on music.

How did the pandemic change things for you with teaching?

The world’s been quite difficult with COVID, and we had to shift things, so many things went online. But at the same time, that was kind of interesting, because I was recording and working and doing everything remotely and still managing to do things. It offered a different twist, and it works for me.

With teaching, I see a lot of new practice and a lot of things new things that people are doing – and you know, it’s invigorating. I think there’s a danger as you get older, that you kind of live in your own little microcosm; I’ve got a whole back catalogue of my history, and [teaching] keeps me exposed and open to loads more different things. That’s the best thing: it’s sort of as much as I’m able to contribute to their stuff, they contribute to my knowledge of how the world works these days.

My past is a reference point, and you sort of reflect on the times and the period in which you live. I don’t feel any pressure to be any particular thing – and I can draw on the past when it suits me … I do the things I want to do anyway!

Music and visual technologies have certainly changed a lot in your history, as has your sound, yeah? You go back to the 70s, and Cabaret Voltaire is a kind of experimental concern, with tape loops – then more house influence in the 80s, and I don’t know what you would call it from the 90s. Have you become immune to people asking, ‘oh, but what about the sound you used to do?’

Yeah, I have, to be quite honest. My past is a reference point, and you sort of reflect on the times and the period in which you live. I don’t feel any pressure to be any particular thing – and I can draw on the past when it suits me. And there are references, what I do currently sometimes still references the past. I don’t want to abandon it, but at the time, I don’t feel particularly captured by it.

I’ve reached the stage where I kind of feel I can do what I want. And if people don’t like it, it doesn’t really matter. Everybody puts everything that they do into their work, so if it’s not appreciated, or it’s dismissed, then it can hurt. But I’m slightly immune to it because I’ve been through it so many times. So I do the things that I want to do anyway!

The title track from Tick Tick Tick

Your lyrics have always hit me as sometimes detached, and sometimes very passionate. In some of the lyrics on Um Dada, you seemed to be focusing on the grind, on working, on the repetitiveness of it. Listening to Tick Tick Tick, where does the inspiration come from? Is it more personal, or universal?

It’s funny because Wrangler has taken up quite a bit of my energy and focus in the last few years, and I obviously write everything for that. Lyrically Wrangler was done in a very – I like your phrase – universal way, it was quite political. Funnily enough, no one really asked me too much about it. But if you look at the last three Wrangler albums – the first one, La Spark, was about global warming and climate stuff. And White Glue was very much about nepotism, politics, and things like that. A Situation was about the toxic and corrosive effects of technology and social media. So they were very political.

The solo stuff is more personal, there are more emotive things in there for me. People tend not to ask me too much about lyrics. I quite like the ambiguity of lyrics; I don’t like forcing people to interpret them. I’ve never tried to dictate what people take from them. I’m always at pains to say that it’s not poetry in the sense that the word and music have got to be in that combination.

I’ve got two daughters, and I work with young people all the time. So there’s a little bit of a shift away from the polemic with Wrangler, and towards the empathetic on a personal and subjective level. I won’t go into too much detail, but “Tick Tick Tick” has that notion of violence and gender violence, and the impact that it has.

How have your lyrics and vocals changed across years and different projects?

Early on in Cabaret Voltaire, my voice was the instrument that was the bit that I could bring that no one else brought into it. And I still think today, the one thing that I can do with all the things I do and all the people I work with – the voice is kind of my tool. I like to use my voice both as a way of articulating ideas and thoughts, but also as something that’s my instrument as well.

And you also started as a bass player in Cabaret Voltaire.

Yeah, although in the first experiments with the Cabs, even before I started playing bass, I was using my voice and processing it with Richard [H. Kirk] and Chris [Watson]. To be quite honest, I was a reluctant vocalist – Chris and Richard made me do it! I didn’t go, ‘hey, you guys need a singer?’

To be quite honest, I was a reluctant vocalist – Chris and Richard made me do it! I didn’t go, ‘hey, you guys need a singer?’

So the voice was my first [instrument], but then the practicalities of it, we started doing gigs. Richard played guitar, we used drum machines, and Chris played tapes, which included some organ stuff. The actual instrumentation in the bass parts came in a little bit late as a response to, ‘well, I’ve got to do something when we stand on stage’ – it was literally that. But I do love the bass, and I do love rhythm, and I played bits of percussion in the very early Cabs stuff as well. I suppose I was a one-man ship, sort of a rhythm section. I was hardly Tina [Weymouth] and Chris [Frantz] combined! [laughs]

With your work in academia, you’re up to date on the newest tools for processing – but simultaneously, technology from the 70s, 80s, and even 90s has become hilariously expensive. You can pay over $20,000 for a Jupiter-8, or $100,000 for a CS-80.

I’m laughing because every bit of vintage equipment that you mentioned, that’s the stuff that I used on the new album. Not because I own it, but because I work with Benge and that’s the studio that we have. At home I work on Ableton [Live], I start writing everything, then I go to the studio and end up changing some of the sounds.

With Um Dada, Benge kind of thought I was mad because I said, “I want to do everything with an [TR-]808. And some 909, some simple sequencing, and just…I want us to try using an organ.” That’s all I wanted, because I’d been working for so long in the studio on the Wrangler stuff, where we can have any instrument that we want – we know we’re lucky! But I wanted to make a record that reduced the palette of sounds I’ve got, so just wanted the simple drum machines and simple bass lines.

When I did Tick Tick Tick it was like, “now fuck this!” I’ve got all the studio equipment. I didn’t use everything, but I loosened up and used more vintage gear. I very much had an idea of what I wanted – I did use the Moog Modular, though I didn’t use the CS-80 much because it’s too fucking complicated, it’s like driving a Ferrari. I wanted a rich sounding record with Tick Tick Tick, so I opened up the toy store a bit.

Other than Ableton, which I use for writing, the [Elektron] Octatrack is the only other more contemporary instrument used on the album – we used it on “Wasteland” and on “The Trial”. We used it to chop beat ups, to just give it those little loopy bits of feel.

“Wasteland” from Tick Tick Tick

Going back to the demo process you talked about – is that mostly in the box when you’re working at home?

I keep a few keyboards here – and some other stuff I keep at the university. I’ll use some Korg synths, the monologue and the microKORG. And I’ve got microphones and effects processors for vocal processing, just sort of toys that anyone can have.

When I came back from Australia, there was no way I’d have the space to set up a studio. So I was happy working just in my own little way. I also have had the massive fortune to work with Benge, together for now 12 years. And so you kind of go, “well, I can’t compete with [Benge’s studio], nor do I need to.”

What are some of your go-to vocal effects these days?

I use a lot of rack gear and things like that; probably the one tool that I go to most is the Eventide (H3000) to harmonize. I use it for flange and doubling effects, and that’s how I get that really nice kind of rich creamy double effect. I also sometimes put my voice through the VCS3 to get the really thin-sounding bit.

I also do double- and triple-track my voice in the studio. And I’ve got an old Roland keyboard vocoder that I used on “The Trial”. For some of the stuff that I do in remixes, I’ll also use the vocal effects in Ableton, there’s some tasty little things you can do in there.

I can’t imagine what it’s like to pick and choose from Benge’s collection! Moving on from the studio, how do you structure things when you play this material live?

It’s really minimal. [My sets] cover five decades – Benge always goes, “they’ll want to hear a Cabs track,” so you’ve got to do a Cabs track which we do. Wrangler do Sensoria and we [Mallinder and Benge] have “Crack Down”. But if I do that, and I play stuff from Pow Wow and Um Dada and Tick Tick Tick as well, it’s a broad thing. It’s straightforward in a sense, we loop stuff, run stems, and Benge plays electronic drums – he’s originally a drummer, and a great one. Benge is really raw live, it’s like a good impersonation of [Neu! drummer] Klaus Dinger.

I process my voice – I use Kaoss Pads and different kinds of voice transformers on my voice. I also play parts a run stuff in sync on a Roland [SP-]404. Every track has a bank of sounds, and I’ll have a keyboard. We want to keep it so we can travel with the whole setup in a car.

Brief clip showing Stephen Mallinder and Benge’s live setup

How are you approaching the focus with live performance vs. in the studio?

The studio process is a whole different process. I don’t need to try and replicate it live. I don’t want to be seen as, “oh, Mal is playing all this [gear].” When I’m doing vocals, I’m enjoying myself and making it live, making it as visceral as I can. I don’t want to be distracted too much by having banks of things to play.

Also, I’m technically not that good [laughs], or musically good. It would be a disaster if I tried to play everything that we did in the studio live! So, you accept that.

Musicians often tend to be dyslexic. And I love the fact that when they write, it becomes this entirely new language.

The titling of your tracks on the new album is interesting – some cryptic titles, not to mention lyrics. Or “ringdropp” having the lower-case r and extra ps. How do you title your tracks?

[Laughs] That’s me. I just thought “Ring Drop” with a capital R looked pretentious, so I said, no. Dais think I’m mental because I’m going “no, it’s got to be a lower-case r otherwise it’s really pretentious.”

Sometimes, the look of words is also there. If it’d just been “ring drop”, it just wouldn’t have had that vibe about it. It’s the aesthetic of words as well. So that’s why, and it’s just me being a bit of a prick [laughs].

Well, language is not math, right? Or at least it doesn’t have to be with steady rules all the time.

That’s the history that I’m working from, people like Prince who invented their own ways with language.

Musicians often tend to be dyslexic. And I love the fact that when they write, it becomes this entirely new language. And I can get it because they write almost phonetically how they’d speak. People who do music, words become quite plastic for us.

One more thing I have to mention – there have been some great Cabaret Voltaire reissues over the past decade, like of the Virgin albums. My personal favorite remains Groovy Laidback and Nasty from after that period, and then I also find your three 90s releases are very underrated. Have you thought to revisit or reissue those?

Yeah, we probably will do that. There’s almost like a whole narrative there that’s slowly coming together – and Richard was looking after that as well. We reached the point where we’re probably looking at reissuing Code, and then also Groovy as well.

This also came up last week with Benge – he went, “man when are you going to reissue Body & Soul?” That was interesting, that period [Cabaret Voltaire’s albums from the early-mid 90s] is one that I really like.

Those were probably the only albums we did that were designed for CD. Everything else up until that point was done with the idea of more condensed versions, with vinyl being the default format. Whereas when we did those albums on our own label [Plastex], it was very much building around the whole ambient feel. I wasn’t doing vocals on all the tracks, we wanted to pull back and we weren’t doing songs.

They didn’t really lend themselves to vinyl releases, but most reissues now vinyl is the default format. So I think we will revisit them, but it might be a case of sort of selecting tracks.

https://stephenmallinder.bandcamp.com