There’s no need to imagine the history and conception of music as beginning and ending in western Europe. The history of music is far older, richer – and stranger than that. Here’s a glimpse of some of that and more resources to help broaden our sense of what music can be.

Hey, I’m glad to switch on the Brandenburg Concerto now and then! There’s something romantic about wandering around the cities where the music I played as a kid came from. But even lovers (and players) of Western European music will discover a more complex, non-standardized, non-Eurocentric view that would make the music experience in general deeper. Look, literally the guy most associated with the critique of Orientalism – Palestinian-American scholar Edward Said – is also a major force in understanding late Beethoven. If anything, understanding western European concert music as the edge of a sea of history rather than some kind of objective musical truth is liberating.

And now that we have any sound at our disposal through synthesis and technology, we might just find ancient Iraqi approaches to string naming or Chinese drum notation could even seem freshly relevant. Developers of MuseScore, Finale, Sibelius, Lilypad, and Dorico, I hope you’re reading this, too.

I’ve talked about the incredible website by Jon Silpayamanant before. But his notation site comes at an important time. On one hand, musical traditions are disappearing and being homogenized. The very value of creativity is thrown into question by big data-powered generative models, which are, by their fundamental nature, normative. On the other, we’re riding a wave of the greatest explosion of notational possibilities ever, from electronic systems like Xenaki’s UPIC to the “hundreds, if not thousands of examples from the 20th century to today” comprising new notations and software. (I think including software, thousands is still too low.) There’s a list of those, too:

Non-CWN Music Notation Software

And as Silpayamanant observes:

One thing to keep in mind with music notation is Sandeep Bhagwati’s (2013a and 2013b) idea of Notational Perspective: the idea that all notations have a context-independent AND contingent features which shapes what’s stable over time and what is malleable.

This is an incomplete list, but as of last week, it had been updated to some 1045 entries. And that just scratches the surface. Some of the scholarship itself comes from recent years; this is an evolving understanding of our human history.

And no, notation doesn’t start in Italy or Germany or even Greece. Have a look at some Cheironomy, which is currently dated to the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, around 2613 to 2494 BCE – etched into stone to show a conductor how to direct singers.

It bothers me that this is represented as western notation and pitch, but here you get an idea of what’s happening with the hieroglyphs:

Early Jewish practice, to which Christian and Muslim vocal practices are deeply indebted, also used a similar system. So when you talk about neumes and the related practice in early church music, that’s all connected to ancient Egyptian and Sumerian practice. (The eastern churches of the Levant and Islamic prayer also share vocal practice characteristics with early vocal traditions of Jewish people, and if you look at historical maps, you’ll immediately work out why.)

You’ll find an extended ancient cheironomy (chironomy) explanation on this archived site :

CHIRONOMY IN THE ANCIENT WORLD

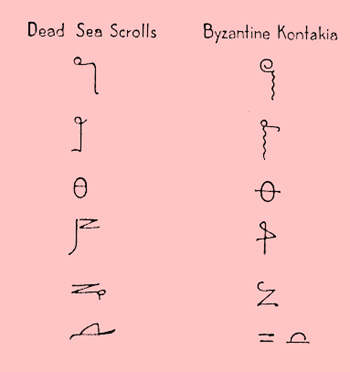

You also get connections between the Dead Sea Scrolls and Byzantine Kontakia (did I blow your mind? Then you’re… okay, a music theory nerd). This comes from Eric Werner, “Musical Aspects of the Dead Sea Scrolls” in The Musical Quarterly (1957, No. 1, p. 24), dedicated to Curt Sachs.

Also from that article:

What does all this have to do with the music of the Temple, or of the cantillation of the Hebrew Bible as such? Are there any indications in the Bible and history that chironomy was used by the biblical authors, or by the Levites?

Indeed there are! Toward the end of King David’s life, he created an “academy” to train Levitical families in the singing of psalms before the LORD. “Four thousand of these,” he said, “shall offer praise to the LORD with the instruments which I have made for praise” (1 Chronicles 23:5, RSV). “David and the chiefs of the service also set apart for the service certain of the sons of Asaph, and of Heman, and of Jeduthun, who should prophesy with lyres (kinnorot), with harps (nevalim), and with cymbals (tsiltsilim)” (1 Chronicles 25:1)

Babylonian notation (in modern Iraq) gets some attention, but we can also head back to ancient Canaan and thereabouts: “the Hurrian Hymns are a collection of music inscribed in cuneiform on clay tablets excavated from the ancient Amorite-Canaanite city of Ugarit (Ras Shamrah in northern Syria).”

Don’t overlook the Sumerians, either. It’s possible these Sumerian traditions linked up with the Indus Valley via trading routes all the way back in 2600-1900 BCE. And I mean, you want some Gilgamesh, you really need it old-school.

Ancient Music: The Sumerians, Part 1

Damn, this is lovely:

Phoenicians of Tyre (hello, my ancestors… erm, possibly), meet other parts of the Mediterranean world millennia ago. On the other side of Asia, yes you get Gupu (“drum notation”) recorded in Liji/禮記 (“Book of Rites”) just around 100 – 1 BCE in China.

And that’s just the ancient world. The Aztecs had notation. In the Majapahit Empire of what is now Indonesia, there was an ekphonetic notation for ritual songs. The list goes on:

There’s something painful about all of this, which is that as I’m writing this, the heart of the ancient sites mentioned are at war, bombs literally falling on stones and towns laid out by the civilizations that built these early notation systems. We have specifically the Israeli defense minister who’s talked about bombing them back to the stone age – a phrase that has a dark history in southeast Asia, where it is associated with American (self-described) war criminal Curtis LeMay, though apparently he didn’t actually say that. More devastation has happened in these sites between now and this time last year than happened through almost the entire linked timeline.

It’s not enough, then, to just be a scholar. These places remain inhabited today, and they’re under threat. But while it’s far from the complete solution, it seems a prerequisite to understanding our shared fate is recognizing that one civilization is not superior to another. Etched into stone is our entangled history of our shared ancestors trying to get each other to sing and play together in tune – presumably with all the same struggles that involves today, with your rock band high school jazz ensemble, or other activity.

The next four millennia of human civilization may need as much preserving as the last four. So yeah, we might actually need a woke mind virus instead – it sounds more useful than that pandemic was.

I don’t know; probably that makes sense if you imagine the voice of Carl Sagan saying it, with slightly improved language. (I have no doubt that Carl Sagan would be saying something like that now, as he was pretty consistent throughout his career.) At least we can view this kind of reflection as related to being human in the present moment. So I really look forward to reading the rest of these projects by Jon Silpayamanant for the same reason.

Arabic Music Theory Bibliography (650-1650) Project

Early Black Musicians, Composers, and Music Scholars (505-1505 CE)

Bibliography of Slave Orchestras and Ensembles

And as I’ve mentioned before, see also:

DAW, Music Production, and Colonialism, a Bibliography

Previously:

Related – meaning to everyone who resisted the thesis of that article, uh, science is tending to be on the non-universal side:

Pythagoras was wrong: there are no universal musical harmonies, study finds [University of Cambridge]