It’s impossible to get perspective on video chat in the middle of a pandemic and the age of Zoom. For fresh eyes, see video chat as if you’re from 1980 – and as employed by a pioneering artist duo.

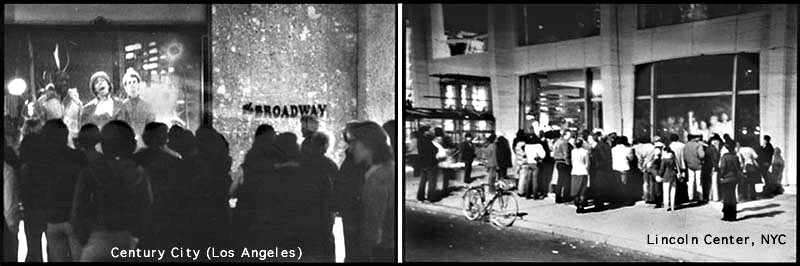

A Hole in Space is unique in that it wasn’t for an audience of engineers or tech-heads, but the general public. The work by artists Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz created a life-sized video link between Los Angeles and New York. And so as pedestrians were treated to a virtual window across physical distance, coast to coast, we get a glimpse into how a 1980 public responded to a then-novel technology.

The project can be fairly dubbed now “the mother of all video chats” – a nod to “the mother of all demos,” the Doug Engelbart talk that packed a ton of future tech – from the mouse to the GUI – into a watershed 1968 demonstration. (To be fair, Engelbart also crammed in some basic video conferencing.)

I’m totally indebted to Olivia Jack, our co-facilitator for this year’s MusicMakers Hacklab at CTM Festival Berlin, for pointing to this example and its significance relevant to her work and others working now in this field.

Full video:

Though to get a feeling for the reactions, check this edited set of excerpts:

I have this video just playing in the full version, and it’s just all gold… a good reminder that the audience is often what the art is about, and for us artists and writers and whatnot to stay humble. (“Barney, I love you!” and “What a revolution that’s going to be…” popping out now. Indeed.) There are spontaneous music performances, a game of “group charades,” just… incredible stuff.

Also, who needs US – Soviet relations (see below) when 1980 can deal with the Cold War between west and east coasts? (“Why don’t you tell us everything you hate about us, and we can tell you everything we hate about you?” I think that was the New York side, ahem.)

More background:

A Hole in Space — envisioning and demonstrating video chat in 1980 [Larry Press, an Information Systems professor and massively experienced researcher]

Hole-In-Space, 1980 [on the official ecafe.com site]

Artists Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz should be known names for anyone interested in electronic art; their work broke new ground in combining satellite telecommunications and artistic conception. Before Hole-in-Space, there was Satellite Arts Project in 1977 – which sought to imagine a performance space without geographical boundaries, some 43 years before arts spaces had to scramble to produce exactly that in the face of the pandemic. These explorations pragmatically explored limitations and possibilities in parallel – and came from a more progressive time in the USA when such projects could get seed funding (from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Corporation for Public Broadcasting).

The duo also established the legendary Electronic Café in Santa Monica California, a “tele-immersive” venue meant to have a persistent role for hosting networked art events – working with a network of similar locations across Europe, Asia, South America, and Australia, and artists like Mark Coniglio (creator of Interactor and Isadora and co-founder of Troika Ranch), Morton Subotnick, Max Mathews, and Pauline Oliveros. Those names you expect – but maybe more surprising, they were also staging dance collaborations between the USA and Glastnost-era USSR.

A 1987 interview by Steve Durland with Galloway, Rabinowitz, and Gene Youngblood deals with the very issue that faces us now – what happens when image and place are intertwined in new ways:

defining the image as place [ecafe museum]

But I think “Hole-in-Space” embodies their approach – and its power – in a unique way.

At first glance, you say – wow, people in 1980 sure had never used Skype or FaceTime. (Though my Kentucky relatives still mused in 2020 at the marvel of speaking to me in Germany in simulated real time.)

But look closer, as there are some details that make this project have such an impact on jaded LA and Manhattan pedestrians – and that remain relevant even in our post-iPhone, cheap-webcam age.

- The video image is at 1:1, life-size scale. That gives onlookers the feeling that they are relating to other humans, and that the virtual space relates to the physical one.

- It allows eye contact and co-presence. Not only is this at a human scale, but the virtual space is aligned with the real one in a way that allows normal human interactions.

- It’s situated in public space. Not to be overlooked is the fact that these videos are positioned in public environments with foot traffic.

- It’s persistent and log-in free. The video runs continuously, without logins or other barriers. You can walk right up to it.

So, 2020, you’re not always stacking up against this very well – and that’s significant. Part of what has caused interactions to slip into strange uncanny valleys over the course of this year is the carelessness with which many of our video interfaces are designed. There’s the infamous Brady Bunch / Hollywood Squares effect of Zoom – made worse, by the way, by the fact that sorting is different on each client. Scale and eye contact and the relationship of virtual and physical space all get easily distorted. (That’s something I have tried to work on manually in some of the panel events I’ve been involved with this year.) There are virtual ways of sorting this – Apple uses digital trickery to re-map faces so eye contact is possible again, though that has also earned the company some criticism.

But we also have to recognize that our over-reliance on laptop and mobile clients has robbed us some of the other features here. Having a persistent, login-free installation (again, something my colleague Olivia emphasized) completely transforms the experience. And there’s no saying that can’t be a solution, too, in 2020.

Here’s a 2017 talk with Kit, going deep into the significance of all of this, in parallel with the history:

I don’t mean to make this brief look at two artists a complete exploration of the history of telepresence in media art. Here’s a nice timeline from Media Kunst Netz with tons of references:

http://www.medienkunstnetz.de/themes/overview_of_media_art/communication/

Back at the beginning of the pandemic, I was in Montreal with MUTEK Festival talking to media art curator Natalia Fuchs. Natalia talked about growing up with exposure to distance communication via Soviet TV across the Union’s far-flung states. That itself probably deserves further exploration – in the mean-time, it’s fascinating to watch late 1980s USA intercept USSR satellite TV in attempts to understand the Soviet mentality:

Maybe the most relevant lesson to me is more mundane – Soviet broadcasters came up with clever ways of time-shifting their programming to cope for the sheer width of the USSR. (It’s the same sun we’re dealing with now.) It’s quite a lot smarter than what a lot of international festivals are doing at the moment, so – while we may not be entirely politically aligned with Soviet TV broadcasters of decades past, we’d do well to borrow their time grid. Someone has gone to the trouble of documenting that on Wikipedia:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Broadcasting_in_the_Soviet_Union#The_timeshift_grid

It’s not a chat, either, but the first live TV broadcast was produced by the BBC in 1967 – and the USSR, originally intended as a participant, pulled out in a political protest:

The rise of video conferencing in 2020 is a direct outgrowth of the pandemic, but it also reveals how much distance was part of our lives to begin with. The ritual in the USA of the Thanksgiving holiday as a family gathering reveals how spread out Americans have gotten from their families. That’s true for me personally – and even though I’ve been on the Internet in some sense since the start of the 90s, it meant my first transatlantic Zoom calls with family in Kentucky.

That pattern repeats itself around the world on every continent. The big issue with COVID-19 is not that it made us more distance, but that it exposed how much distance was already in our lives, by suddenly taking away the mechanisms that allowed us to navigate that distance. Open borders, constant air travel, and public health itself were under assault this year. And the reality is that even as large swaths of the global population did not take those things for granted, a privileged class did.

My bias is the same as always, though. I believe that we’ll find new and innovative ideas partly through some education in what happened before, and talking to artists and researchers who understand and appreciate those approaches.

I do hope we explore this more – and I’m excited to have people like Olivia onboard as we chart our way through these possibilities. I feel the same as everyone – I am eager to be in the same room with other people. But I also know that we have a lot more distance work to do in 2021, vaccines notwithstanding, and that even as we do move out of the COVID-19 era, we can do better with how we handle distance and virtual image.

Now get those satellites ready.

KIT GALLOWAY & SHERRIE RABINOWITZ

OVERVIEW OF A QUARTER CENTURY OF PIONEERING ARTISTIC ACHIEVEMENTS 1975-2000