Forget clean: we want things dirtier.

What can you do with a two-oscillator synth to retain the classic design, but give creative sound makers a twist? This is looking like yet another week of new analog synths, as California celebates the biggest American music trade show, NAMM. Moog this week unveiled the Sub Phatty analog synth as their answer to the question. It’s still a very Moog approach to what a synth should be, but adds an aggressive edge thanks to the addition of the new Multidrive circuit, a filter-stage distortion and overdrive.

We saw the guts of the Sub Phatty and none other than synth legend Herb Deutsch walking through its sound capabilities, so we already know a lot about the new Moog – and found a number of features to like. Now, we get to see what it looks like, and hear more details.

And since product specs don’t say anything, we decided to go behind-the-scenes at Moog to find out a little more about how its creators imagined this new musical instrument. Moog’s Steve Dunnington talks to CDM about the process of designing this instrument, back to the early days he spent with Bob Moog himself.

Let’s run down those specs and pricing/availability first, to kick things off:

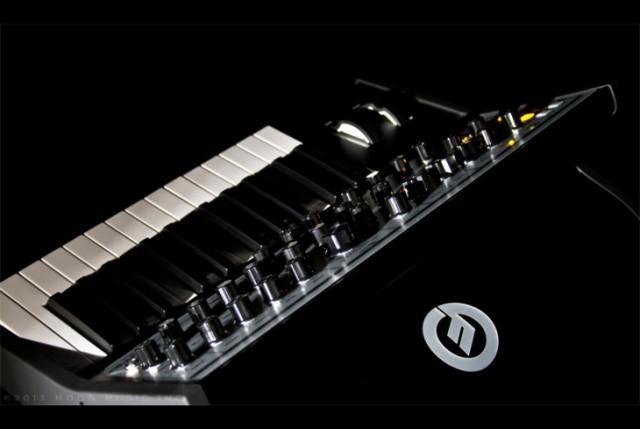

Looking at home astride Moog’s pedals, the Sub Phatty. Photo courtesy Moog Music, exclusive debut on CDM.

- 25 full-sized keys (what, as opposed to mini keys? Why, are people talking about that this week?)

- 31 knobs

- Newly-designed sound engine powers the two variable-waveshape oscillators “that require almost no warm-up time.” (Not necessarily true on the Slim Phatty, so worth mentioning.)

- Multidrive circuit combines OTA distortion and FET drive.

- 4×4 preset matrix = 16 presets, plus the ability to set filter poles, pitch bend amount, toggle legato/glide modes, etc.

- Sub Phatty software editor (standalone/plug-in).

- Route different sources to the filter/overdrive based on the Mixer section.

- Square-wave sub oscillator (hence the name).

- Noise generator (ideal for adding things like percussion sounds).

Price (retail): US$1099, which should mean a street in this magical sub-$1000 range that keeps heating up for analog lovers lately

Availability: March 2013.

Interview

Steve explains more of the thinking behind those specs, and how they translate into an actual instrument.

First, Steve, can you tell us a little bit about what you do at Moog? How did you wind up with this job; what’s your background?

My job title is “Product Development Specialist” which is a way of saying I help design our products – mostly the analog and hardware aspects of design. I’m part of a team that works together to develop Moog synthesizers (and other products too), including the Sub Phatty. I started working for Bob in December 1994 (we were called Big Briar back then). I first knew him from classes I took at UNC – Asheville. When I first started, I just worked on making Series 91 theremins. There were 5 of us including Bob. We’ve come quite a long way from there.

My background before that is in music as a multi-instrumentalist/experimentalist, but I was also good at math and took physics for engineers in college because that was the “real” physics classes and was more challenging. I got into the technical aspect of the job by starting as a production technician. In 1994 I was machining custom parts, doing sheet metal work and stuffing PCBs all in our little shop. From there I had stints managing production, doing marketing, service, tech support, you name it. As we grew there was a need for an engineering technician, which is what I enjoy, and the move to that position lead me to what I do today.

So, we know there are some things that are new in the Sub Phatty. What elements of the design carry over from the Little Phatty; what do they have in common?

The synth architecture is very familiar – it’s the same voice structure used in most classic Moog synths. Sound sources get mixed, filtered, then amplified. The audio path is 100% analog. What you gain with a familiar voice architecture is ease of learning and use. It doesn’t take you forever to learn the instrument and it’s fast to come up with a wide variety of musical sounds. We’ve tweaked a lot of the aspects of the circuits though – for instance the waveshaping circuit for the VCOs is the same topology as that used in the Voyager and LP, but with some subtle changes that makes the instrument have its own sound.

A lot of people are unclear on the gestation of these instruments. (That is, I think products are designed faster than they actually are!) When did the Sub Phatty come about, and what was the original idea?

Interestingly, some of the ideas date back to the original Little Phatty, which was originally envisioned as a knobby 2-oscillator synth. Based on feedback at the time, we opted to go a different route. Now, analog synths are appreciated for what they are – unique tools with their own sound and character for making music. Because people today have embraced analog synths more, a knobby synth isn’t seen as something scary like an airplane cockpit, but something inviting to explore. That warms our hearts.

“Grit” seems to be a theme – I’m already loving what I’m hearing and seeing of the Multidrive circuit. Can you tell us a little bit about how this was designed, and how it relates to the Moog legacy (particularly the Minimoog)? It seems a welcome time to get overdriven filter stages back in Moogland, but what was it that specifically motivated this now?

Well, we do live in the south of the U.S., and we sometimes eat grits for breakfast, so maybe there is a geographical-culinary connection. Ed.: Cheese grits, please? Make a synth as delicious as cheese grits, says the Kentucky-born editor. -PK

But seriously, we wanted to find a way to go beyond the overload circuit in the Little Phatty – which is based on mixer feedback and post-filter asymmetrical clipping. The LP overload can sound pretty hairy – but it doesn’t scream, and we wanted this synth to be able to get really dirty. The “scream” comes from a combo of overdriving the filter input with the mixer output, then getting overdrive in the filter output section followed by a fun little JFET drive stage which at low levels is warm and furry but gets snarly as the filter output section smacks it harder. The entire thing is really sensitive to the levels of the VCOs in the mixer, the shapes of the waves, the setting of the filter, so there are a lot of tonal nooks and crannies to explore. It’s a lot of fun.

Are there other elements of the design beyond that obvious one that fit the same theme?

There are things that aren’t on the panel that can be gotten to with a few button presses that add to the fun – there’s Note Sync (or VCO gate reset) for the oscillators available, so you always have a predictable oscillator phase at the start of each note for consistent power during repetitive bass lines. Also something new for our synths is the “Beat” control – which allows you to set a beat frequency between VCO1 and VCO2 that tracks through the range of the instrument.

Usually when you detune VCOs on an analog synth, the beat frequency doubles/ halves with octave changes. When you have a fixed beat frequency, the basses sound detuned and fat, but it actually sounds less detuned as you play up the keyboard. That’s an awesome thing to explore in conjunction with the VCO gate reset feature. This has been done on digital synths, but why not on analog? It sounds really good.

The noise generator does seem unique; what was the design concept behind it?

Well it’s an analog noise source – I think what’s unique about it is how you can distort it in the mixer and with the Multidrive control – it gets a kind of unstable, rough sounding edge to it. It’s also voiced so it has plenty of low end for beefy percussive sounds.

The interface looks really beautiful, really clean to me, and seems to represent a new aesthetic. What kind of evolution did you have to work through to arrive at this solution?

Thanks for that – there was a lot of batting around ideas that resulted in what you see. Design is a process – some of it logic-driven, some is emotional. A lot of it is starting with an idea from one person about what something should be and letting everybody on the team digest it until it is clear what is essential, what can be discarded, and what needs to be refined. As long as you have a passion for it, the folks who end up owning and using your gear benefit! The one thing I’ve found about product design is that there are always compromises made to get a product to market – the more features, the less possible it is to satisfy everybody, because possibilities multiply exponentially with complexity. The trick is in minimizing the impact on the end-user of any choices you make and making something that has lasting use, and that people can have fun with. After all, these are musical instruments and making music by yourself or with others using your tools should be a good time.

Sounds

Video Demos

The blog ProAudioStar did a series of demos on this instrument.

Blog post, complete with downloadable Ableton Live session (hey, nice – may have to steal that idea!):

Moog Sub Phatty Demonstration with Nolan DeCoster

The blog also sets up the Sub Phatty with Jerry Wonda for some artist opining:

And our friend Huston Singletary, one of my favorite clinicians and sound designers (with Ableton, no less), has high praise for the instrument – and I really respect Huston’s opinion:

Sweetwater’s demo:

Product page:

http://www.moogmusic.com/products/phattys/sub-phatty