Now, following a century of recording and broadcast, where does musical performance go next? That challenges not just space or culture, but reimagining the place of time itself in the performance.

Berlin is a fitting place to contemplate time. Once home to Albert Einstein, it helped incubate modern general relativity. At its southwest is Mendelsohn’s Einsteinturm; it has the Kaiser Wilhelm Society in its DNA. Adlershof, a short S-Bahn ride away, is home to the enormous BESSY II synchotron photon radiation source (particle accelerator.)

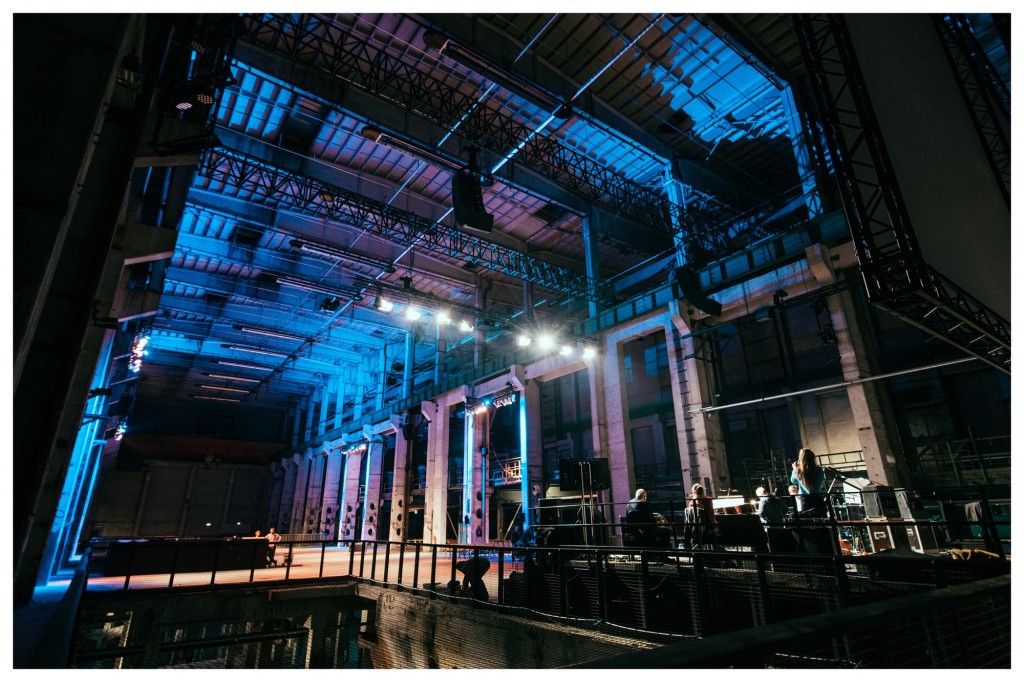

To redefine time, you have to first redefine space. Kraftwerk, the cavernous venue of The Long Now (and Berlin Atonal). Photo: Camille Blake.

And now the Berliner Festspiele has taken on no less lofty goal than pondering time and the meaning of “now” in its programming. A four-year project entitled “100 Years of Now” attempts to penetrate the socio-political and historical forces around how we think of time, in everything from talks to performances. (Even the concept of the panel discussion can take on a deeper, reflective quality, with a series entitled “Thinking Together.”) My favorite moment from the opening – composers colliding with molecular biologists, lecture with performance, and something entitled a “Mucilaginous Omniverse” realized by Evelina Domnitch and Dmitry Gelfand. An enlarged image of liquids made an immersive sensory picture of wave phenomena as a sort of guest-star performer. More:

Time’s Attack on the Rest of Life: Experiment [Haus der Kulturen der Welt]

You can also read the Goethe Institut reporting on the new focus on time, as it happened last year:

THE LONG NOW

Maerzmusik, to the outside world what would be called a “contemporary music festival,” rebranded last year under the direction of curator Berno Odo Polzer as a “Festival for Time Issues.” This isn’t just new music or concerts for the sake of it: it imagines that each concert could challenge the notion of time.

And then, there’s what culminates this weekend in Kraftwerk, the enormous former power plant that looms above the current location of techno hub Tresor.

“The Long Now” is a marathon, yes. But it’s a marathon with a purpose.

The twentieth century was the century of the recording, the broadcast, TCP/IP. That technology threatened to consume live performance, but then a funny thing happened: the business of the recording industry started to implode, too.

Now, in the 21st Century, the culture of the virtual might well take up all-out battle with the culture of the real.

“The Long Now” could be the face of what “concert music” could become. It’s no accident that it has emerged from the fertile ground of the Berlin club industry. It’s not hard to convince Berlin musicgoers to disrupt their circadian rhythms and sleep cycles, given that’s the normal workout here in the land of the Saturday-to-Monday (or worse) afterhours. So it’s perhaps unsurprising that the venue managed by Tresor and a short walk from Berghain and Kater Blau would offer up a come-when-you-like, 30-hour weekend sprint with the possibility of reentry.

Already this week, in the same space, Max Richter’s “SLEEP” suggested the coexistence of slumber and musical reverie – complete with beds. “The Long Now” takes that to a logical conclusion.

In a bigger-than-even-cathedrals space, Kraftwerk is welcoming in its concrete blankness. As last year, installations will run continuously. Cots will invite people to recline, or snooze.

And this freedom opens up new durational possibilities – it lets duration be a negotiated meeting between audience and artist, rather than an imposed convention.

Here’s what the organizers say about that:

“The Long Now” is a place for the enduring present. A space in which time itself can unfold, where the sense of time can take uncharted paths and even depart…

Embracing musical worlds, from the avant-garde to experimental electronics, Ambient and Noise, “The Long Now” is made for sonic and bodily experiences of an exceptional kind. Whether lying, standing, sitting, dancing or eating, you are invited to stay in this chronosphere and give yourself over to “The Long Now”.

Okay, now this may all sound like lofty arty bollocks, but stay with us here. The actual experience of entering and exiting “The Long Now,” assisted by the grandness of the setting, is eminently pleasurable – whatever the theoretical frame.

Last year was an enormous musical highlight for me, and I decided to stay for most of the full duration (with some breaks, to retain mental composure). We were treated to classics by Morton Feldman, a no-brainer choice for an experiment in duration and concert music. Composer Phill Niblock, whose presence in the space was itself re-energizing (his eyes never once looked droopy), filled the night with mesmerizing, long tones.

There were new commissions, too, the highlight being new work by Eric Holm. And Actress produced an explosive finish to the cycle.

This isn’t just about theory. Experiencing the narrative of music set in this way is an opportunity to meditate on one’s own perception of time. It suggests this can be a way of understanding what music actually is – of giving us the power to change that temporal awareness.

“The Long Now” hasn’t gotten nearly the attention that the summer festival in the same space, cooler-and-trendier Atonal, has. But it should. This year, Berno Odo Polzer again joins Atonal curators Laurens von Oswald and Harry Glass, and the program is even broader. Yes, you get Feldman. Yes, you get Cage (not only 4’33” but also the colossal 1992 Fifty-Eight for that very number of wind instruments).

But you also get a rich program of live electronics and new commissions.

Dan Vincente (Acronym), Rashad Becker, Moritz von Oswald, and Baba Electronica all have new premieres. Robert Curgenven heads into the Turrell skyspaces and comes back with new microtonal recordings. Sweden’s acid-friendly monster TM404 is live, too, from the dance side of the coin, along with the DJ talents of Objekt, Nina (of Golden Pudel), and Miles Whittaker. And you get a who’s who of live electronics: Murcof, Klara Lewis, Biosphere, Caterina Barbieri, Dalhous.

You can read about “La Substance, but in English” at the website of Stockholm’s modern art museum:

Mårten Spångberg about La Substance, but in English

Ponder this bit:

The performances are, as in are, and they exist like the ocean, which is one united whole – something entirely superior that encompasses everything – there are lots of things in the ocean, but the ocean is always one.

I’ve also been particularly enjoying Klara Lewis’ output of late, and she’s got a packed schedule around Europe this summer from what I’ve seen. Here’s a listen to what she’s doing:

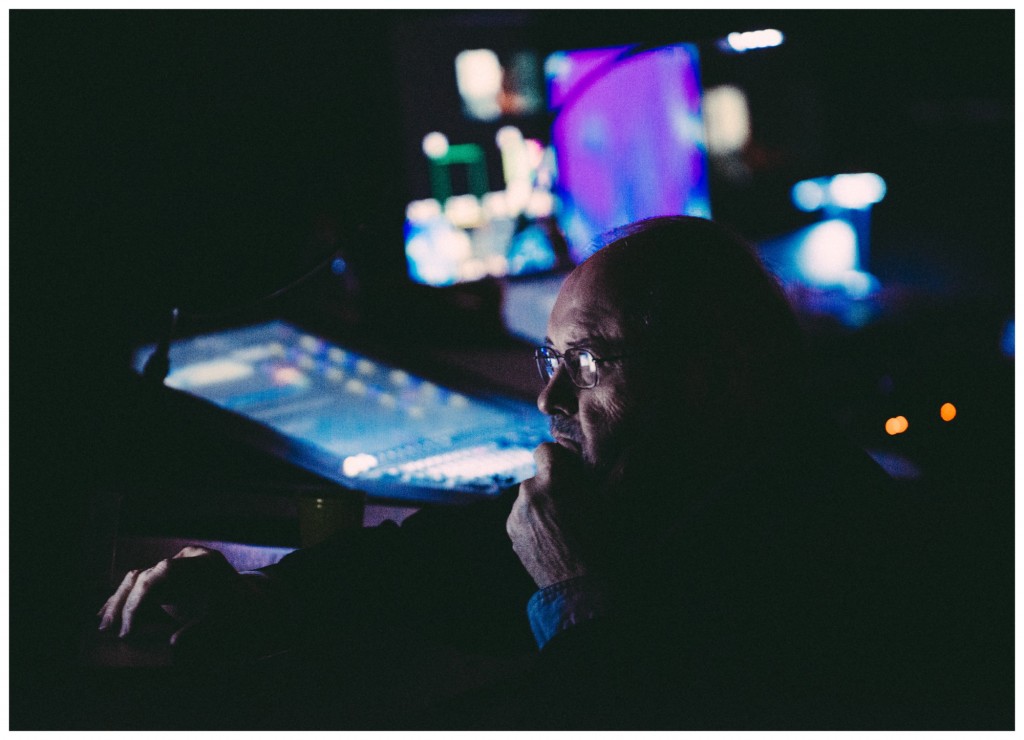

Caterina Barbieri, in the power plant control room at Berlin Atonal last summer. Photo courtesy the artist.

And some audiovisual delights from Caterina Barbieri (in collaboration with Giovanni Brunetto, not necessarily having anything to do with The Long Now but something I find entrancing):

VUOTO ESTREMAMENTE ALTO (UHV) from UHV on Vimeo.

Check out the full program:

The Long Now [MaerzMusik]

But I hope this is more than just a compelling one-off in Berlin. Like the Prussian seeds of general relativity itself, I hope this sort of found space, mixed installation and concert, open marathon concert format finds its way into other spaces, too. I hope that history of phenomena like the Cage-ian Musicircus aren’t supplanted by more-staid, museum-style “Classical” presentations – I hope that today, as it was for Cage, the concert can still be radical.