Brainpipe is a psychedellic journey down the neural pathways, a long, strange trip into the minds of an unusual band of independent game designers. And while some games demand muscular graphics cards or brilliant flat panels, this is one that requires playing with headphones. The immersive sense of the descent down this brain’s pathway is entirely dependent on its sound. While even big development houses often license sound engines, the band of hard-core designers at Digital Eel also rolled their own interactive audio code to make the sounds fully seamless.

Designers and developers Iikka Keränen (the primary coder) and Rich Carlson spoke to me about their work. (They make reference to artist Bill “Phosphorous” Sears, as well.) In the process, they have a lot to say about the design process, about ambient sound design and composition, that goes well beyond just the gaming world. This isn’t just about gaming: it’s truly about digital music.

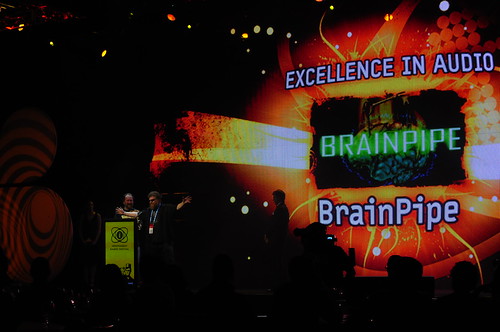

Digital Eel has won three excellence in audio awards over the past six years from the Independent Games Festival, including, most recently, a nomination for the psychedellic hit “Brainpipe” at the Game Developer Conference this spring. Incredibly, though, says Digital Eel’s Brainpipe, in that time no one has interviewed them about the sound in their games. Independent of the interview, Rich concede to me the challenge of getting people to focus on sound:

People are focused on graphics –and gameplay– and, you know, sound always gets the short shrift, even at game companies. Sound and music are always the smallest slice of the development budget pie.

But not so at Digital Eel. Sound and music are integral and integrated with design from the first moment we have something happening on the screen. We feel it must be, and not just sfx but music, especially music which so often sounds like something….like dressing, something painted on, like makeup or apartment paint to help cover up the picture holes on the walls.

Brainpipe Game Page (with Mac/Windows download links – demos available so if you hate this, you’ll find out!)

Brainpipe on Steam (Windows only)

At a glance:

Engine: Custom

Favorite inspiration: demoscene, The Dig, Star Control II, Stockhausen, Varese, Morton Subotnick, Ussachevsky

Special acheivements: hiding loop points, creating a seamless acoustic descent, tapping into your subconscious

Peter: Let’s talk about the game mechanic. Some of it feels familiar – this descent through a cylindrical pipe – but there’s something quirky and unique about your take on it. How did you settle on the interaction mechanic?

Iikka: This was quite literally the first thing I programmed for Brainpipe. We were trying to come up with a new "short" game after putting another larger project on the back burner because we didn’t have enough free time to work on it. Within a few hours I had the basic control scheme and the moving pipe running on the screen. This is similar to how some of our other short games (Plasmaworm, Dr. Blob’s Organism) got started; the first prototype is something you can play with. After that there were tweaks of course, but the feel stayed much the same.

Rich: Everybody likes the "wormhole effect" you see in space shows and movies, and we do, too, so we wanted to do something like that. Iikka got the pipe happening and we began to play with it as a prototype. Originally, we just wanted the player to fly down the pipe having a kind of zen experience as the speed slowly increased, and that’s all. Not much of game there, though.

We were talking about music right away and how the sound, the intensity of the patterns and colors on the pipe walls, and the speed of traveling through the pipe should all work together. [We wanted] a kind of triple whammy to suck the player in deeper and deeper — a strong, cumulative effect.

We did add obstacles and specials, things to scoop up, and plenty of things to avoid that look pretty but are lethal. But the blend of music, color and pattern complexity, and speed remained as we’d originally intended — this began very early on in the game’s development.

Making sure each obstacle has a sustained sound so you can hear it coming in the distance in front of you and then hear it pass by and recede with Doppler shift certainly adds to the audio illusion.

I think the kicker is the way the intensity ramps in the game. It’s sort of like a rising sawtooth waveform-shaped thing. During each level, the intensity, the speed increases, Then, between each level, the intensity drops to give you a breather before the next level begins. Each time the intensity drops, it is still at a higher intensity level than during the previous level break, and all of this ramps upward.

It kind of coaxes you along. You might not realize that you’re actually moving faster and faster each level for a few levels. It’s a good training system. Eventually you’ll get it as the game approaches its highest intensity levels and speeds. Anyway, I still think it’s really cool.

The sensation of synesthesia is something a handful of game designers have tried to achieve. What are some of the games that have inspired you? Are there games you feel have reached that fusion of sound and visuals?

Iikka: My personal influence is the "demoscene" that I was a part of when I was younger; it’s a subculture of programmers and artists using computers to create non-interactive but real time audio-visual experiences.

Rich: For me, LucasArts’ adventure game, The Dig, with its seamless looping of various Wagner themes and so on. The music would morph as scenes changed. It was an amazing piece of work.

The music from Star Control II innovated with music and visuals, and it directly inspired the music for Strange Adventures in Infinite Space and Weird Worlds: Return to Infinite Space. The idea that each alien race should have their own theme music came from there (though this kind of thing is less unusual now than it was when SC2 was originally released), as did the idea to attach separate and distinctly different music to each thing, category of thing, item, window, pop up announcement –every action in the game and every flick of the interface … like a toddler’s "busy box" of sound.

Back to Brainpipe, other areas of music outside of games inspired us as well. Aleatoric, musique concrete, avant garde — stuff Bill just naturally creates and stuff I’ve always loved since I was a kid. [I checked] out the LP’s at the library by Stockhausen, Varese, Morton Subotnick, Ussachevsky, all these wonderful pre-synthsizer electronic sound and found sound composers. And the records were awesome because they were always in pristine condition — relatively few others ever checked them out.

[It’s] mindblowing stuff to listen to while you’re listening to Steppenwolf on your Japanese transistor radio and playing John Phillips Sousa in your Junior High band. Liberating. Of course this stuff scares some people and some people react to it negatively –all strongly– but if you listen to it, put together by someone who pays attention to details while intuitively knowing what they’re doing, you can hear the music in the sighing of pond reeds, or on the heavy end, the music within industrial clamor and the beauty in the beast.

That seemed perfect for Brainpipe which really demanded a whole different musical approach and completely different kinds of music produced in ways that are not normal — not typical at all.

I love that you talk about sound being integral with the design process. Even for a musician, though, thinking in more than one medium can be a challenge. How do you approach this in terms of design; how do you make it part of the process in practice?

Rich: When we make a game, music and sound are in right away. From the first couple of hours, the basic prototype is on the screen, so they began to shape the sonic style of the game immediately.

Because sound and music are growing up at the same time as the art and programming is, all these elements influence each other pretty equally, so you don’t get music and sound that sound "separate" or tacked-on. You get sound you can’t turn off, and you don’t want to, because it’s actually part of the game.

Sounds can also influence and inspire and change things. You might be after a certain sound effect, but then you stumble across something else that’s much cooler, so the animation of a visual effect is changed to match the sound.

What was the compositional process like on this game? The sound design / sound score clearly fuse – with these recurrent "whooshing" sounds as an added layer. How were these assembled?

Rich: Basically what you’re hearing is a series of loops. Most of them are 16-second loops.

I knew right away that "music" with beats wasn’t the way to go. The music had to create a soundscape, something that supports a mindscape, really — pun intended — rather than making you want to tap your foot. It had to smoothly transition just as the "art" on the pipe wall and the speed of traveling through the pipe smoothly transition in the game.

I also knew that the music had to have a kind of primal power and evoke a sense of mystery about what is supposed to be going on and what is being revealed. Bill was very much into this too.

At the same time, we wanted it to reflect the random thoughts floating through and bouncing around inside your brain. One of the best ways to accomplish this was to leave conventional music behind, which is what Bill and I ended up doing.

It was important that the loops be seamless. If you’re working with beats and grooves, that’s a very easy thing to do — it starts on one and ends on four. You simply loop that, attaching the end to the beginning and it sounds fine because, for the most part, that’s how a bass/drums/guitar combo plays.

On top of that I knew we needed loops that didn’t sound like loops. Loops gamers wouldn’t notice were loops, with no obvious "breaks" where the end of a loop would be obviously attached to the beginning, or the beginning of another. The loops had to have no beginning or end!

The sources for the loops were varied. There are very successful loops in the game that are extremely simple, comprised of only two or three tracks or elements. [But] some of them are monsters mapping out to 32 tracks or more. Again, the idea was to create loops that don’t sound like loops with a range that would reach an orchestral level of density.

Finally, the soundtrack loops had to blend seamlessly with each other while increasing in intensity. One way to do this, of course, is to cross fade them, but that wasn’t going to be enough. The intensity and the components of each loop needed to be gauged so a dramatic and appropriate intensity ramp was reached. I think we came very close to nailing it, but I want to keep experimenting with this. We can go farther now, having only scratched the surface.

Can you talk about some of the found sounds that are collaged into the result? (I’m hearing the TARDIS materializing…)

Rich: I don’t want to spoil the magic trick but, like most who do music and audio, I collect sounds from all kinds of sources. I’ve been doing it for a long time, so if you listen carefully you’ll hear things from old TV shows, records, radio shows, interviews, sound effects records, and God knows what else folded in there.

The soundtrack is meant to represent the background music of your own brain so references to "real life" should resonate –especially, we hoped, on an unconscious level.

I don’t want to list all the sources — some of them are in the credits – because what is going on is also a sound trivia game. It’s the Mystery Science Theater of game music, but the gamer is provoked to make guesses and speculate.

You noted that part of why you embarked on building your own sound engine was that OpenAL [a standard, open, cross-platform API for spatial audio] wound up being inadequate. What were some of the obstacles you encountered? Have you found other independent game creators dealing with the same issues?

Iikka: We had to switch away from OpenAL because it made repeating clicking sounds on common integrated audio hardware. The lack of features is not terribly important, as you can always just use OpenAL as the output channel for your own sound mixing system. My sound code would be perfectly happy living on top of OpenAL if it was universally supported.

Sound is a rather underappreciated and underdeveloped area in games. To many game developers, especially smaller ones, it’s enough that it "makes a sound when something happens". The focus of development is very much on the visuals.

It seems like game audio lacks a functioning standard. OpenAL is promising but lacks some of the maturity of, say, the OpenGL API which game visuals can use. What’s your take on the landscape? Is there hope that a new standard or engine could address these issues, and result perhaps in better sound and music design in games?

Iikka: I think it’s possible that OpenAL will mature to a point that it will work reliably on all common hardware some day, and at least form a standard foundation for people to base their sound engines on so they won’t need to learn a new API for each operating system they support.

As for workflow and design, I don’t view these as dependent on what is under the hood; they are the result of the mindset among the team members. Certainly one could imagine development tools that allow an audio artist to work more directly with the game, but a good first step is just making sure that everybody involved in the project is involved in designing the work flow.

Can you describe your custom sound engine? What functionality did you find you wanted to build into it? What would you want to put in the next iteration?

Iikka: I call it "eelmix". It’s a modular sound system in which sound sources, filters and mixers are arranged in a tree structure, like a scene graph of sorts. It’s analogous to musical instruments wired together, eventually converging to a master output to speakers.

The main goal was the modularity, the system makes it easy to make a "box" that takes a sound output (from any source), mangles it in some interesting way, and then feeds it to where it was originally going, without modifying either the source or the destination. We haven’t really used the full capabilities of this yet but the modular system is also useful for things like separating UI ("2d") sounds from the game ("3d") sounds that makes balancing them easier. And it eliminates the need to conform to some preset number of "channels".

There are other lesser goals, like eliminating clipping by using 32-bit precision internally and simulating a non-linear response curve when rendering the final output. This is a very simple and useful bit of code that really improves sound quality when there’s tons of sounds being played.

Going into the future, what’s left is mostly just filling in some blanks like including basic prefab filters, making sure that every kind of sound source can use every kind of sound sample, that sort of stuff.

Indie games it seems, like larger games, have struggled a bit on sound and music – perhaps because of the lack of better tools. But what are some smaller, experimental, or independent titles you feel have done good things with their soundtracks?

Rich: A couple of indie games have had sound and music that was really special, I thought. I loved the music from Saints & Sinners Bowling a few years ago. Just great stuff that nestled right in there so you didn’t want to turn off, and that’s the true test.

Musaic Box which I encountered at this year’s IGF [Independent Games Festival] uses conventional music ingeniously. You solve musical puzzles by ear, assembling melodies to reach certain goals. I think music is actually more integral to this game than it is in Brainpipe because it’s directly a part of gameplay. You couldn’t play Musaic Box without it.

Flow stood out to me for doing something really quite gentle and tasteful and, well, flowy — even the soundtrack lived up to the game’s name. That’s important I think, and that gets back to some of the things I’ve already said here.

Sounds to Hear

To head deeper into the strange sonic world the Digital Eels inhabit, Rich sent along some additional sonic resources:

Weird Worlds stuff

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/the_single.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/mfbtpv2_320Kbps.mp3Misc. stuff from different games old & new:

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/voidprobe.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/blok.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/drblob.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/forest.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/plasmaworm.mp3

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/vault/haircut.mp3An interview (Omaha Sternberg interviewing Bill, "Phosphorous") with a couple snippets of Brainpipe music in it:

http://www.digital-eel.com/files/omahaphos_intermix1_160.mp3

Enjoy. The game is really unusual, so I look forward to hearing what CDM readers think of the experience. And if you have other games (or other interactive experiences) about which you’d like to learn more or get an interview, let us know.