This year has kicked off with a renewed conversation about tuning in electronic music. Khyam Allami has helped ignite that interest with free online browser tools anyone can explore, plus performances showcasing them – and has been outspoken about the philosophy behind them and why they matter. Here’s a deep dive into that work.

While I was in the process of editing this interview, a story on Pitchfork blew up online – I think partly because of the reach of that publication, but also a provocative headline:

Decolonizing Electronic Music Starts With Its Software [Pitchfork]

It’s also worth a read, with additional artist conversations – and Jace Clayton’s Sufi Plugins for Max for Live gets a nod, too. But I think it’s important to first grasp how much of tuning we’re leaving out if we just leave things at 12-tone equal temperament.

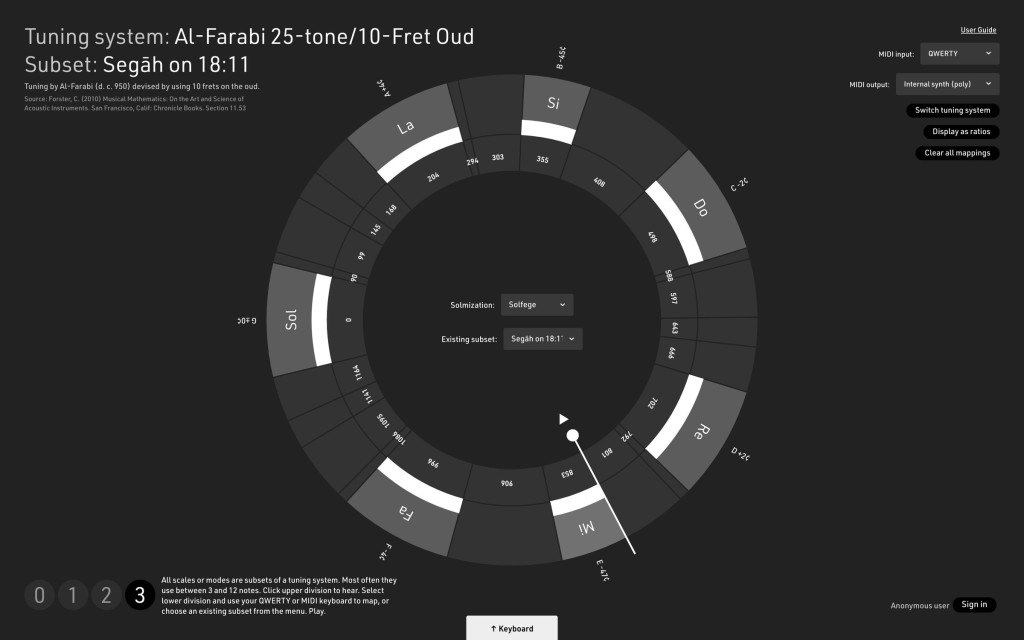

And do go check the tool.

https://khyamallami.com/Apotome-Khyam-Allami-x-Counterpoint

Apotome and Leimma were developed by Khyam in collaboration with Counterpoint, the creative studio by Tero Parviainen and Samuel Diggins, which specializes in a ton of stuff we’re into (generative design, music and technology, expressive AI):

It also features Web-based instruments (Web Audio Modules) by Jari Kleimola.

Prologue – beyond the preset

For anyone with a passion for sound and listening, this should be a topic with immediate interest. Remember the first time you went beyond the “001” piano preset? Machines have opened all kinds of new possibilities for sound and expression. You’d probably already scoff at sticking to 120 bpm, 4/4, 1-bar patterns. Yet viewed in the context of most of the history of the world’s musical practices, that’s more or less what a 12-tone equal temperament (12-TET) default is. It is quite literally the “001 GRND PNO” vanilla default of tuning.

First, having read some online comments on this discussion so far, we should be clear about terms – familiar to many of you since you’ve made it this far, but worth spreading to everyone else. Many people are confusing “tuning” with “tuning reference” – the reference being a starting pitch (like an oboe playing some concert A, such as 440 Hz) but not the relationship of other pitches on the instrument to that pitch. That confusion is amplified by many electronic instruments only providing this setting.

Tuning references of some kind are embodied in different ways in different musical practices. Javanese gamelans, for instance, might be modeled after existing instruments. When we visited a popular builder on the outskirts of Yogyakarta, he even began with a simple (KORG, maybe) digital tuner and some starting frequencies he told me were based on an older ensemble. But then the tuning process for these metallophones meant adding and removing metal, and eventually fine adjustment by banging with a hammer and listening.

Unless you’re playing only one-note jams, though, you will invariably tune other pitches. Tuning can refer to any frequencies to which an instrument is made to sound or a singer’s performance produces. On acoustic instruments, this would mean adjusting strings, or where holes are measured on a wind instrument, or where frets or located, and so on. On electronic instruments, theoretically, anything is possible. And that’s before getting to the many possibilities for weights, melodic implications, and ways these frequencies are used in context.

It’s common to hear musicians make assumptions that these particular presets have some kind of objective reality. But… they don’t. Relative to the harmonic series, many so-called “consonant” intervals in 12-TET are out of tune enough to produce beating; they’re a mathematical compromise and they sound like it. Musicians also regularly conflate 12-tone equal temperament with tuning systems like Bach’s own Well-Tempered Clavier, which used a related temperament but not the same one – and the same can be said of the likely performance practice of many composers considered pillars of “classical” concert music. (The old “what would composer X do with a modern electronic instrument” question might first be – “scream why is this so out of tune?” The tunings are related but – sonically it’s a really different experience, obvious to most ears, not just a piano tuner’s.)

That’s not to center this on European concert music. Rather, I think it’s worth opening our minds and disavowing them of some of the misconceptions about how tuning works. And most musicians are initially taught with an explanation that was at best, misleading or reductive, and at worst, flat out wrong, so much so that your piano tuner would tell you as much if you bothered to talk to them. (Speaking of re-centering, Europe may have been one of the last to “discover” 12-tone equal temperament – look to pioneers outside Europe, like Zhu Zaiyu of Ming dynasty-era China, among others.)

So let’s listen to someone who is able to re-center our hearing – and remind us that what is presented as a global “standard” represents a tiny fraction of musical practice across time or geography. And if that raises some questions about why that did become the standard – well, that’s the point, too.

Here’s that conversation – plus, for further viewing, check out the extending panel discussion with Deena Abdelwahed, Khyam Allami, Matana Roberts, and Tero Parviainen, moderated by our friend Dahlia Borsche here in Berlin, on escaping Western normalization and its restrictions and bias:

Peter: What was your own musical experience – both Arabic music and otherwise? How did that lead you to the research path you’re on now?

Khyam: I was born in Damascus to Iraqi parents and moved to London when I was nine. But Arabic and Iraqi music were always in the air – whether it was my father singing rural Iraqi Aṭwār whilst cooking, or my mother singing Fairuz during private gatherings at home.

I started to learn the violin at age 8 but I wasn’t taught Arabic violin; it was sadly all based on European classical music. In London, I continued with the violin but soon got sick of playing Pirates of Penzance in the school orchestra. When I discovered grunge, punk, and then particularly Tool, Killing Joke, Rage Against the Machine, Soundgarden, and the Melvins, I left the violin behind and started to play electric bass, guitar, and then got hooked on the drums. I started a couple of bands with friends, Art of Burning Water and Ursa, then slowly got into prog rock, mostly King Crimson, Yes, and Rush.

Slowly I started searching out more weird music and in the late 90s stumbled upon Secret Chiefs 3, the epic project by Trey Spruance from Mr. Bungle and Faith No More. The album Hurqalya: 2nd Grand Constitution And Bylaws floored me, particularly because of its use of Middle Eastern tunings and melodies, within a mix of such outlier genres and soundscapes.

Trey was always generous about sharing his influences, intertwined within various mystical articulations, via his Web of Mimicry label website and forum. That’s where I discovered the mysticism associated with music in the works of Joscelyn Godwin and the epic Mugham of Qasim Alimov from Azerbaijan. Finally, I found the thread that linked Middle Eastern music, Punk, and Prog with my own mystical and spiritual leanings.

The subject of tuning is deeply integrated into the cosmologies of many world cultures. As I became more interested in actively listening to music from Azerbaijan, Iran, India and the Arab world I wanted to create weird music like that of Secret Chiefs 3, but became frustrated with the tuning limitations of digital software, and the tediously complex workarounds that were available. I had no money, and my friends weren’t interested in such complex connections, plus I didn’t really know anything about Middle Eastern music on a practical level.

Then the second invasion and destruction of Iraq happened in 2003 and I felt completely out of balance and out of place. This led to reconnecting with my family’s history, with the realities of the displacement, the politics and the culture. This was something my parents had actively tried to dissuade me from engaging with as a form of protection. We were refugees and living a basic existence, they wanted me to have opportunities and a life they were unable to have.

Once I started to learn Oud with Iraqi musician Ehsan Emam in London, everything I was reading about became palpable and visceral. I could feel the difference and started to appreciate why these links between music, mathematics, and cosmological world views existed. This led me to forget about music-making with digital tools and focus on studying the oud.

I wanted to dedicate myself to music but I wanted to learn about music from across the world, not study Western classical composition or jazz or music production, etc. So I ended up enrolling myself in the Ethnomusicology BA program at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. I studied Hindustani Tabla with Sanju Sahai whilst continuing my oud studies with Ehsan Emam. I graduated with honors which led to a scholarship to do a master’s degree at the same university and a lot of travels across the Middle East to study and research. During that time I never stopped listening to all kinds of music, the frustration with digital tools continued, and finally, I decided to take things into my own hands a few years ago.

It’s a long and complex trail, but I think it quite clearly shows how I ended up where I am today.

In this talk, artist and researcher Khyam Allami gives a short introduction to »Apotome« – a transcultural browser-based generative music system focused on using microtonal tuning systems and their subsets (scales/modes). Alongside its sister application, »Leimma«, which allows intuitive and immediate browser-based exploration of tunings, it is the final part in a trilogy of music-making tools that Allami has been developing in recent years. Resulting from Allami’s current PhD research and his in-depth collaboration with Counterpoint, the creative studio run by Tero Parviainen and Samuel Diggins, these applications are an effort to highlight the cultural asymmetries and biases inherent in modern music-making tools, alongside their interconnected web of musical, educational, cultural, social, and political ramifications. They are an attempt to present decolonised music applications that allows music-makers from any culture to have the freedom of a musical tabula rasa (blank slate) and explore their individual creative ideas with modern tools, but without a specific end-result as a goal.

I know your creation of these tools connects as well to your doctoral research; what’s the relationship with your research work?

Yes, I’m in the last year of doctoral research at the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire in the UK supervised by Sean Clancy and Scott Wilson from the University of Birmingham. My doctorate is practice-based—what is referred to as Artistic Research—and is focused on composing a repertoire of contemporary and experimental Arabic music. Leimma and Apotome are not my doctorate; they are a by-product, if you can believe it.

I needed tools like these to better explore my artistic and conceptual desires. With a small funding opportunity, I decided to create something that everyone would be able to use for both learning and music making because I know how complex this subject is and how difficult the workarounds are. I see my own creative capacities as being quite limited, so I want to inspire people in any way that I can, whether that be starting a record label or launching a project like this. Doing this as part of my PhD research kills two birds with one stone, and also allows the project to be free and non-commercial.

What was the genesis of these tools initially? There’s Leimma, there’s Apotome – was the idea always to have the two separated, one as instrument and one as direct exploration of tuning?

The core idea was always two tools: one to learn, explore, and create transcultural tuning systems [Leimma], and one to use generative processes to inspire unconventional ideas related to these musical cultures with tuning as a core fundamental element [Apotome].

Artistic freedom to me means choice, but choosing without knowledge can only take one so far. We also have a lot to unlearn, before we can relearn and start truly breaking with conventions.

What informed the tools’ design choices? It seems you focused in part on maximizing usability and accessibility – including the use of sequencers and LFOs in Apotome that is quite approachable – but also producing something a bit open-ended?

The core principles behind Leimma and Apotome are to treat all musical cultures as equal, and provide accessible and intuitive choices with as little insinuation and bias as possible, and more importantly without pseudo-neutral defaults.

You’ll notice that when you open Apotome, nothing will work until a tuning system and a subset are chosen. You can do everything else first, but nothing will work until you make that decision.

The act of having to actively choose this most fundamental element of music is the default state.

That said, we also have a random button that will randomly generate all the parameters, including the tuning and subset. But that is also a choice, and I think an important one for experimentation.

As for the technical capabilities, we tried our best to include as comprehensive a feature set as possible, whilst staying true to the core principles and encouraging people to experiment.

I don’t believe that generative systems can create great music on their own, but they can help us to hear unlikely ideas and therefore increase our sensitivities beyond our conditioning.

This is a unique collaboration between theory and online development. How did the cooperation with Counterpoint [the development studio] come about, and how did you work together or exchange ideas?

Tero and Sam from Counterpoint are exceptional collaborators. This entire project is really a synthesis of all our interests and skills and I don’t think I could have done it with anyone else.

I saw Tero’s presentation about generative music online after he presented it at Ableton’s Loop 2017. I loved the way he presented all the information, in-browser, with interactive musical capabilities. It reminded me of the same excitement I had when I first saw Ableton’s browser-based learning environments – learning music and learning synths.

How Generative Music Works [Tero Parviainen]

I had been wanting to develop a generative system for Arabic maqām based music, but Tero’s presentation and these browser-based technical possibilities got my mind racing. I reached out to Tero via Twitter, sent a long rambling email as is usual, and we met in London when they passed through for their Electronium project at the Barbican with Yuri Suzuki. They were immediately excited, I managed to find a small amount of money, and we got to work.

I basically had the initial templates and ideas drafted, but then pages of emails and GitHub threads led to both Sam and Tero contributing many core and fundamental ideas that made this project what it is.

Most importantly, Sam and Tero were open to all the self-critique and interrogation that I was putting myself through every step of the way. That helped me see things that I wouldn’t have seen, and I’m certain it was the same for them.

This project was never only about the technicalities – as Tero said in our CTM panel discussion, getting things to work technically was the easiest part. Tuning capabilities and workarounds have existed for decades, so it would be disingenuous of me to present our work as pioneering in that sense. But where it differs, and is unique, is in its accessibility, perspective, presentation and philosophy.

There’s so much that has happened in the past weeks – also panel discussions, collaborations, and then unleashing this on the festival-going audience (and people like me). Did you encounter anything surprising in all of that? Anything that you’ll take back to the lab as it were, either with these tools or your own research?

Ideas for improvement haven’t ceased, it’s just a matter of time and money. As for my own research, I’m constantly stop-starting, revisiting and redeveloping ideas, it’s a continuous process.

What I have been surprised by is some of the unimaginative reactions to this project, particularly as a result of the Pitchfork article. That people are so triggered means that we still have a long way to go in unpacking this subject and being able to communicate it. I will always do my best to adjust my language or perspective in order to more articulately express my ideas, so that too is ongoing. But I do look forward to taking some time out to purely focus on music-making and being creative.

I was really struck by the live performances. Can you tell us a bit about how those collaborating artists worked with the system?

Faten Kanaan, Tommi (Tot Onyx), Nene H, Tyler Friedman, Enyang Ha and Lucy Railton were an absolute dream team to work with. They are inspiring and beautiful people. It was a great opportunity to work with them.

Basically, Faten Kanaan and I had the roles of composers/conductors, whilst the musicians had the freedom to create the sounds and timbral dynamics. This meant that we individually developed compositional ideas in Apotome, gave the musicians some guidance, and then fleshed them out all together during the rehearsals.

Faten connected remotely to my laptop from her home in New York, and controlled Apotome live. And I did the same, but on site.

Apotome sent out the musical data via MIDI including the accurate tunings, whilst the musicians handled the sonics.

What’s the future plan for the online tools? I think you said you don’t plan to open-source them for various reasons, but you will make them freely accessible?

That’s right, they won’t be open sourced, but they will remain online and freely accessible.

I’m also actively trying to secure funding to develop them further alongside another list of ideas I have, so if anyone has any tips, please get in touch!

This is a huge question, but just to give people a teaser – you mentioned talking about best practices. What sorts of things could be done better in tools that do already have support for MTS, Scala, .TUN – what could make these more musically expressive and useful?

It is huge and I don’t think it is a responsibility we can place solely on the backs of individual developers or manufacturers. It needs to be a communal effort.

Firstly, if we start calling it tuning and not microtonality, we will already be making a huge leap. It is shocking that a subject so fundamental to music, tuning, has been so sidelined because of equal temperament and the mono-cultural hegemony of European classical music. Let alone the association of microtonality to experimental western music. It’s hard for people who don’t know or understand it to appreciate how political and problematic it is. More on that below.

Secondly, I think starting from a critical place where all musical cultures are treated as equally important and valid, as opposed to making an effort towards equality by just including a tainted version of them, is the key. This needs in-depth research and a nuanced understanding of how music is made across the world.

Even Leimma is unable to fully fulfill that because it doesn’t allow for non-octave repeating tunings, nor the more esoteric Western experimental tunings. I knew that, and it was a choice to start by accommodating the majority and highlighting the complex ramifications of the subject.

Centering the majority of musical cultures, whilst providing an accessible means to engage with them and highlighting the repressed possibilities was a priority for this first step. There is so much that we can learn from these many and very complex cultures that have been sidelined, misinterpreted and misrepresented – without overloading the users with tons of options. Most musicians don’t even know this is a problem, so I thought it best to start here and slowly expand.

Thirdly, just having support for tuning and tuning data files isn’t enough. It doesn’t provide any of the most basic contextual information – especially because many tuning systems are not scales, they are a series of pitches (sets) from which scales and modes (subsets) are made. That is a fundamental principle. For me, the only company that has managed to do this with any credibility is Celemony, with the tuning features in Melodyne Editor or Studio.

Just giving musicians the ability to load up any of the 5000+ files in the Scala scale archive without any context maintains the exoticization, othering and even the fetishisation of this subject. I love Scala, the format and the freely downloadable Scale archive, but it is problematic – many of the files, particularly those pertaining to non-Western and non-experimental music don’t have information on their sources, nor any guidance for how they should be used.

Compare that with the amount of instructional information on synthesis, or how to use a plugin or the complex routing of modulation matrixes in software synths, or even how to play the piano or the guitar, then you can see the wider picture.

Leimma tries to highlight this by including sources, and basic information such as root, primary, and secondary notes for the subsets. Just that alone, is huge for learning and de-exoticizing.

But as I said, this isn’t something that we can put on the backs of software and hardware developers alone. It needs to be a communal effort.

Most musicians don’t know anything about tuning, and many who claim they do, think it’s about changing A4=440 Hz to something else, because that is the only time they have engaged with the term when using their music software and hardware. It isn’t.

Most musicians don’t know that equal temperament comes from an ideology loaded with supremacy, one in which European classical music is seen as the most advanced music on the planet. Even the most respected outlier electronic musicians fawn at an opportunity to work with an orchestra. Why, if the orchestra and therefore Western classical music is not regarded as the apex of musical culture and musical expression?

Most musicians from non-Western cultures have no idea that when they tune their instruments using a seemingly harmless equal temperament digital tuner or play their melodies on equal-tempered instruments and software, that their individual and cultural voice has already been mediated.

I’ll repeat that this subject isn’t just about tuning capabilities, it’s about how the tools represent “music” and methods for music-making, which is intrinsically tied to knowledge, economy, and therefore power.

These are hard facts to swallow. They make us feel stupid, or like we’ve been conned into our own subjugation. They make us defend ourselves from being associated with racism. But we have to face them, and we need to face them with nuanced discourse, accessible solutions and educational efforts that accompany them.

Even the most lauded musicians today who don’t have a formal musical education have learned from somewhere – most likely a combination of friends, manuals, books, magazines, and YouTube videos. With the capabilities at our disposal, there is no need to only consider institutional education as the main source of information, even if institutional education is also in dire need of an overhaul when it comes to this subject.

I have ideas for how to move forward with this, but it will need a lot of support and collaboration to make it happen.

Side note to that, I remain interested in how tools accommodate not only scales and fixed tunings, but different practices of performance and modal inflections. We can obviously just make better interfaces that allow musicians to play these and rely on the ear – not only make everything algorithmic and automatic. But are there ways of incorporating some of that musical practice into the pitch model in software?

There are plenty of ways to incorporate these ideas technically, but without the proper research, contextual information and educational efforts, it will be tokenistic. Let’s unpack the Native Instruments’ Middle East as part of their Discovery series.

[Ed.: I reached out to Native Instruments for comment. But what follows is detailed constructive criticism and a call to realize greater potential for this kind of detailed instrument that I think is useful industry-wide – enough so I almost want to go develop new tools after reading it.]

Native Instruments responds that they “have been actively reviewing the series over the past months and there will be changes forthcoming, with more details to be shared soon.” We’ll stay in touch if that situation evolves.]

Clearly, a lot of effort and time went into developing this product. It is amazing in its capabilities and particularly its integration with NKS and Komplete Kontrol hardware. A superb initiative for a million different reasons, but…

From my perspective, it should have been called “Turkey”, not “Middle East”, just as they have “India” and “Cuba” and “Balinese Gamelan”. Instead they maintain orientalism by putting everything in the same [package], most likely for economic reasons — [or] that “Middle East” is more alluring and will probably sell more than just “Turkey”.

“Middle East” is presented as being Middle Eastern even though all the instruments, except a few percussion, are Turkish or presented as Turkish (regardless of the fact that they are regional). The limited microtonally tuned scales available are Turkish (12) and Arabic (12), and although they can be modified, you can’t add your own – very limiting and not comprehensive.

In the context of all the work they did, why didn’t they make the effort to add Arab and Persian instruments? If that would have been too costly, how difficult would it have been for them to consider that instruments like the Qanūn/Kanun, Oud and Nay span across Middle Eastern cultures and therefore adjust the presentation, include Persian tunings and modes, alongside the ability to add one’s own, and even more included scales? That’s just a little bit of extra research/consultancy.

[Ed.: Just to re-emphasize an important point here for those unfamiliar with the musical topic – the Oud and Nay are both used in a wider array of cultural practices and geographies than presented in the package, but also here are made to use a narrower body of music because of technical restrictions. It illustrates that attempts to “generalize” a product may actually do the opposite. And these are widely used, not particularly rare, instruments.]

The same goes for the manual, it has not even the slightest overview of what Tukish Makam is, let alone the links between it and Arab maqām or Persian Dastgāh, nor even a list of what scales are included or how to navigate them. Information about rhythm and rhythmic cycles is equally lacking.

The only accompanying YouTube video’s presentation and discussion of the product is equally problematic, including the line “the library draws from Arabic, Turkish and Persian musical traditions” and a horrendously out of tune, nonsensical example, before going on to call the Turkish Saz, a Zaz.

It’s clear from the marketing that the product is directed at non-Middle Eastern musicians, so why such little research and insight into the musical culture itself? What exactly are users supposed to “discover”? Especially when so much effort has clearly gone into the product’s concept and development.

Then, when we look at the credits, we see the imbalance; an entirely European, Berlin-based product team, recording Turkish, Lebanese, Persian and German musicians at a studio in Istanbul, but no direct involvement of musicians with experience in Turkish, Arabic or Persian musical practice working on the product’s development or implementation.

“India”’s manual is equally lacking in musical information, sadly doesn’t even mention the musicians’ names, and the only non-Europeans credited are Ricky Kej and Akash Dey for “MIDI Groove Programming”.

My point is not that the Native Instruments team are racist orientalists, but that the inherited remnants of orientalism, which stem from imperialism and colonialism, are rife in this scenario. A musical culture is being mediated and represented by a team of Europeans, whilst the native musicians and musical culture being represented at its core are just a means to an end.

With a little more budget and effort, they could have had three individual products – Turkish, Arab, Persian – plus a cohesive “Middle East” bundle. Rather than work a tiny little bit harder, or reach out to native consultants who have the knowledge, to create something truly representative and empowering, we end up with orientalist marketing and “add authentic Middle Eastern flavor to your compositions”.

Native Instruments has also responded that custom scale creation is possible in Discovery Series: Middle East, as well as India and West Africa volumes from that series. Note that this process does not include .TUN/Scala import support. They also point us to a more advanced engine in YANGQIN; see the documentation. That interface uses western staff notation and note names, however – note the more graphical interface in Leimma for contrast.

What do you make of how many tools fail to go beyond 12-TET? Apart from really limited hardware where you have fixed tuning tables, something like a software instrument ought to do this quite readily, yes? Is some of this starting to crack or change as there’s more international exchange?

I think this limitation is due to the inherited biases I have mentioned above. The more we can have a nuanced, open, and respectful discussion about these issues, the better.

At some point, the industry that controls music-making will need to take heed and come together, with the involvement of knowledgeable native musicians and researchers, to create a proper solution.

They tried with MTS but it was rarely implemented, and even when implemented it was inadequate. Maybe because the contextualization and importance was not well communicated? Maybe because they had little to no non-white or non-anglo-European musicians involved? Maybe because most instrument manufacturers don’t really care? I don’t know.

Finally, I’m curious to return to the evocative titles of these tools. What’s the connection to the mathematical concept “apotome” – it seems both quantifiably and cosmologically linked to the possibility of pitch continuum, no? And then there’s a specific meaning in Pythagorean tuning?

Leimma and Apotome take their names from musical intervals devised by ancient Greek theorists, and are often referred to as Pythagorean intervals.

A leimma (also written; limma) has a value of 256/243 or 90.225 cents and an apotome has a value of 2187/2048 or 113.685 cents. Arab theorists referred to the limma as al-bāqīya and the apotome as al-infiṣāl, and alongside the interval of a Pythagorian comma (531441:524288 or 23.460 cents), used them to delineate tuning systems on the oud (Farmer 1957:459).

Although the historical writings relating to tuning systems go back to approx 2500 BC in Mesopotamia (Mirelman 2013) and precisely tuned lithophones existed in China around 900 B.C (Kuttner 1964:122), it is often Greek, i.e. Western, theorists who are given the credit for developing the core tuning systems and theories used today.

The use of these terms as names is a desire to re-appropriate them in today’s context, whilst advocating for a celebration of difference across cultures, ideas, methods, and sounds in music-making.

Check out the performances and artistic collaborations from CTM to see and hear these concepts and the tools in motion – including in Khyam’s hands, among other artists.

Oh, plus – on his channel, you can catch Khyam playing the Oud, as well, which is essential listening:

Resources:

https://isartum.net/ [online tools]

https://www.ctm-festival.de/festival-2021/