Keep techno nerdy? We go in the studio to find out how Copenhagen’s CTRLS [Token] has developed his own sound, and how it relates to the tech he uses.

Away from the whims of techno fashion and its potential for cookie-cutter aesthetic chasing, there are cats like CTRLS, aka Troels Knudsen of Copenhagen. With some nine EPs to his name, he’s been steadily honing a craft – one with roots back in 90s trackers. In other words, he’s just the person to ask about process, because his sound is built from inside out instead of outside in.

And Routing is a song of experience – never overcomplicated, always clear, always groovy. You know, smart. And from that foundation, it gets to be weird and original. This is Troels who loves sounds making sounds you’ll love.

It’s also label Token Records (led by artist Kr!z) at its best. I thought Danish rush hours involved bicycles or something, so I suspect Troels secretly lives in the future. “Rush Hour” has a timeless groove going:

“Crash” is also heavy and grimy, with an off-kilter gesture that makes it keep falling forward, like some more industrial take on those Drinking Bird toys:

“Highway”‘s glitchy, weird noise percussion takes on this 90s IDM feel, but perfectly mixed I think and with a sense of both space and friendly shuffle:

“The Shortest Path” comes closer to what you might associate with the Token sound, but places it in Troels’ sense of wit and charm – at just a moment when the “serious” European techno scene threatens to get incurably gloomy:

(Also welcome: when you buy the album, you get “locked grooves” to use as DJ tools – leaving the tracks themselves to be more headphone-listening friendly.)

An older release, but I really love the concept, sound, and video (a reactive visual installation by Rune Abro & Yonathan Sonntag) – check out “Incoming Data” from 2015, also on Token:

So with that in mind, I got a chance to give us a look inside his studio and tools. And I was curious how that path led from machine to musical voice, from esoteric tracker knowledge to Internet-enabled music culture, because it speaks I think to other musicians, too.

Of course, for all that Internet power, I’m indebted to another obsessively hard-working Copenhagen techno talent, Anastasia Kristensen, for connecting me with Troels. I’ll say this about both Anastasia and Troels: these are people who are disciplined, and whose discipline then enables them to really play.

First off, your work is full of detailed rhythms and a wide sonic palette. What are you working with, in terms of vocabulary? How does your technology impact that vocabulary?

I spent a couple of years taking keyboard and piano lessons and I’ve got a bit of academic audio engineering under my belt, as well as the experience I’ve got from my part-time mix work. In general, I guess I’ve become the guy people ask for technical solutions, locally, so there’s rarely a mix issue I can’t work my way around these days. Everything else has been uncovered on the Web and by generally making sure I have some skilled people in my circle. Learning synths and sound design has been a very personal journey — as it should be, if you ask me — and I came out the other side as a bit of a synth nerd. I generally like to be a bit effective about it all, as well as understanding what I’m working with. So that combined with me being naturally curious tends to lead me towards more modern techniques and gear.

I also had some great mentors that showed me a lot of interesting things like polymeters, but other then fun tricks like that, I don’t tend to get too deep into music theory with Ctrls tracks. For example, scales feel a bit restrictive in that context.

Take us back a little bit. I know a lot of our most avid audience are deeply rooted tracker and demoscene and the sort of IDM niche communities of the Internet … some of them back to the early BBS days. At what point did you get your feet wet in that Internet world?

A friend introduced me to the tracker scene in the mid 90s. The BBS scene was still alive at the time, and I don’t think many artists in Denmark realized that trackers were, as such, fully fledged samplers. Also, the modules were wide open: sounds and techniques were right there to learn from. Today, people would kill to look into their heroes’ projects, but that was normal for us. Ed.: That was certainly the response recently to Aphex Twin showing off tracker secrets.

And it’s information that wasn’t really available in any books. When I made my way onto the actual Web, it was even easier to access. For a while, that was my main inspiration and I’d look to new tracker releases more then I would commercial releases. I also remember my music teacher being shocked when I showed him Fast Tracker 2 compared to the thousands of euros he had recommended me to spend on hardware samplers and synths.

I still sometimes try to think back to how I’d solve problems or how the tracker artists had their workarounds. For example, you didn’t have any swing/groove control in Fast Tracker 2; instead, you had to manually delay every second 16th with a command, throughout the entire track. It felt very empowering and inspiring, but that being said, I don’t want to go back to hex note editing and automation ever again.

Did it make a difference, having that more international, Internet-driven culture at your fingertips, coming from Denmark?

The internet made a huge difference for me when I started. We were into bass music at the time and were finding the UK scene ridiculously hard to break into. Granted, the vibe is more open and international in Europe, but the UK labels at the time had no faith in producers not from there. But through the net, I had access to a much deeper network then you were likely to find just by partying and traveling to London, and so I got one of the first (maybe the very first) proper Danish drum’n’bass releases off the back of that. Other then that, it is of course extremely convenient to be close to some of the most significant scenes, but it took a long time for it to properly rub off on traditional and conservative little Denmark.

What was your first encounter then with making music with machines?

A couple years of piano and keyboard lessons and I headed straight for computer sequencers. I was lucky to have a music teacher that really encouraged my curiosity for technology and production. My first tunes were done with an old Roland arranger keyboard, [Creative Labs] SoundBlaster 16 and a Windows 3.11 sequencer called Musicator, that used staff notes instead of piano roll. [These tunes] were recorded (mixed down is too generous) onto cassette. Then trackers and samplers came into my life, and things got a lot easier.

Now, there are some pretty quirky vibes on this latest Token outing. What’s the spirit of this record; where did you draw that inspiration from?

I just don’t want to sound like everybody else, and I guess my palette has evolved around that ethos. I definitely have a thing for very mechanical and futuristic (to my mind) grooves, but I spend a whole bunch of time trying to make sure that the sounds have a realistic quality to them, even though they’re likely to never occur in nature – particularly sounds that resemble the human voice is something I seem to steer towards.

How did you set up the album conceptually – particularly the flow, as far as lengths, grooves, and so on?

It was actually set up to be a fairly straight club record with variety spread out across the tracks, especially as far as intensity and rhythms go.

In general, I tend to focus more on what I don’t want a record to do and how I avoid those things while still making high quality dance music. Things come together much easier for me that way. There’s a traffic theme to the whole thing simply because I’m looking to make things move, within my self-defined futurism framework.

What will we find in your studio now; what machines are currently meaningful to your music?

Right now, the centerpieces are a [Mutable Instruments] Ambika [synth] and my LXR drum machine going into Rostec preamps and converters. They’re very versatile instruments and most of the new Ctrls tracks are sourced just from those two with all sequencing, effects and processing running off the computer. I’m really into Unfiltered Audio plug-ins for processing lately. They seem to be some of the ones that gets the closest to nice digital hardware boxes, in terms of anti aliasing and overall definition. There’s nothing like a processor that can turn a sound completely on its head and still sound good. I do still use a few VST synths, mostly u-he zebra2 and bazille.

[Ed.: The Ambika is now no longer made by Mutable Instruments, but as it’s open source hardware, it lives on as a DIY project maintained elsewhere.]

The most esoteric piece is an old Kurzweil K2000, which sounds absolutely phenomenal. Ed.: The K2000 is best understood as a digital sampler/workstation with a semi-modular facility inside for creating custom patches. That deep architecture, called V.A.S.T., was true to its name, with elaborate options for routing signal to create advanced sounds.

It’s got this magic ratio of grit and definition and depth that you just don’t find in most modern instruments straight out of the box. Being an early 90s digital workstation it is a nightmare to program, so it’s not made it on to a lot of Ctrls tracks because of that, but I’m still keeping it until it breaks and I can’t get it fixed anymore. I’ve not heard any plug-in that gets even close for strings, textures, and atmospherics. If your voicing is good, it just blends straight into the track without any processing. It’s one of those pieces that can make you think the developers’ industry aren’t being half as ambitious as they should be. Ed.: This is an interesting point here – apart from making me feel a little old now that the K2000 and 1990s are vintage or esoteric. I suspect details of Kurzweil’s architecture as well as good sound design and preset voicing, so readers, feel free to discuss in comments.

The most important kit is probably the monitors. I’m working with a customized set of small speakers that, to my ears, outperform other brands in the same price range I spent on them. Most important being that they’re not fatiguing, so I can work on them all day. If you’re mostly in the box, I think a good monitoring situation makes things a lot easier, and customizing can make that much more affordable as you’re not dealing with mass production issues but can just focus on pure quality and omit a lot of the compromises. Also, should they break I can have ‘em up and running again the same day. In general, most things in my studio can be fixed without having to be shipped off.

I really like that your live approach feels really improvisational. And it’s very digital. How do you set up your live set? How do you relate it to track ideas without, you know, getting stuck playing tracks?

I’ve been through a bunch of iterations: prototypes running everything live off VSTs, just DJing my own material, bit of hardware, just Ableton and controllers etc. Right now, I’ve basically set Ableton up to be an extended version of Traktor [DJ] to play loops and use effects along with jamming on the LXR [drum machine]. I also drag my nice converters out to make absolutely sure that if the system is great, I’ll be able to take full advantage. Going through a preset playlist was never that attractive to me; it gets old so quickly. And Ableton being Ableton, it does require some engineering work to get it to sound like a DJ set with mastered material. But with that out of the way, I can really relax on stage and just vibe.

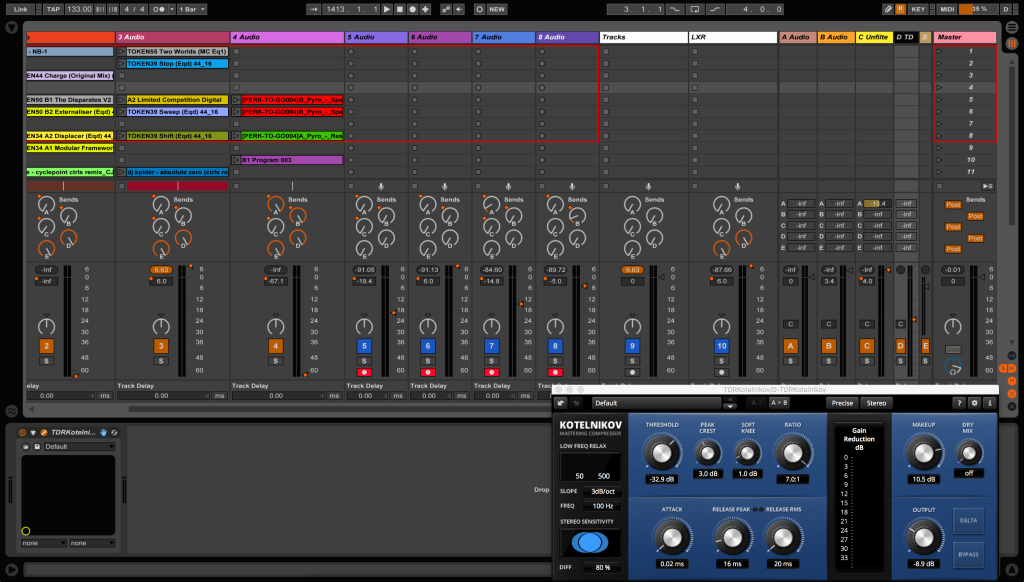

Inside the CTRLS live set – simple, but with stuff to control.

As for being stuck playing tracks — it’s pretty important to realize that your recorded music is what most people go to see you for, or at least that seems to be the case with me. And to a point you can have a more profound impact if there’s that connection of elements that the crowd can recognize.

I learned this after my laptop almost died right before a Berghain live set. I had to dj my own tunes off my iPad, and somehow got a bit of LXR going on top. It felt a bit underwhelming to execute after all the preparation I’d done but nobody noticed anything, the set got a great reaction and I got a bunch of compliments for my poker face. So, after that I started to tweak the setup to capture that feeling but still provide something people wouldn’t have heard before.

I STRONGLY advise all live performers to have a simple plan b, and not just give up if something goes wrong. It takes away a monumental amount of stress and disappointment if your setup is very complex.

Okay, interesting. And yes, I love redundancy. Actually, maybe the fact that I got the improv bit wrong says something – I thought it was improvised, but in fact preparing the tracks in this case allowed more play on top, which can also be useful. I see you’re making use of the Livid BASE controller, too; how do you have that mapped?

It’s basically set up to be an audio mixer: four track/loop channels with three effects sends and a looper with adjustable length, and the rest to level the LXR voices as well as a few custom parameters controlling plug-ins that are processing the drum machine.

What’s exciting you now as far as what you listen to? It seems techno is fairly focused in the moment on a small circle of people as far as innovation in elements like timbre, within some particular constraints. Without getting too far into name dropping, what do you feel is important to you? Is this a genre that’s moving forward, in regards to those artists?

Yes, it’s definitely moving forward, although it is a pretty narrow field of producers actually pushing the envelope. But I don’t think it needs to stop within the constraints you mention. It’s such a wide-open field right now as there’s a bunch of cross-pollination going into electro, noise, bass music. and lately oldschool trance. That openness is one of the main things that attracted me to techno in the first place. Especially as an artist myself it’s very inviting that you can take that attitude and latch it onto pretty much any sound palette.

In general, I just really appreciate creative and expressive sound design married with great music. It’s one of the main characteristics that keep the genre very fresh for me, personally. Historically and as far as innovation goes, there’s so much more to techno then the Roland TR boxes [808, 909, etc.] and their inherent workflows. I really appreciate artists (new and old) that have the imagination to step out of that “loop,” or bend it to their will.

I’m trying to be very aware of not conditioning myself into a total music geek with no sense for naivety. But by now I don’t think it’s disputable that technology, and how involved people get with it, plays a massive role in how the genre’s evolving, so I equally try to maintain my curiosity about new sounds, performance types and contexts. The music obviously comes first, but no one’s been able to offer me a good explanation of where that ends and the noise starts. So I think there’s plenty of reasons to keep exploring and to stay curious.

From the always-excellent Deep Space Helsinki, here you get a mix with his inspirations in mind:

And the release:

https://www.beatport.com/release/routing/1980748

Follow him here:

https://www.facebook.com/controeller/

Studio photos: Rune Abro.