It’s a master class in Western “common practice” music and its power. It decodes complex music theory and its impact on the mind. It’s also got some deeply entertaining action with a bearded psychiatrist operating a reel-to-reel machine and filters. Let’s watch this 1975 episode of BBC’s Horizon on the science of music and MUZAK.

Somewhere in this full 43-minute documentary, which the BBC has uploaded from their archives, you’ll find some deep revelations about fascist aesthetics and the normative power of music as a colonial and political tool. Embedded in that nicely done, in-depth analysis are a lot of assumptions about the universality of music that reveal a bias against and othering of the world’s musical diversity.

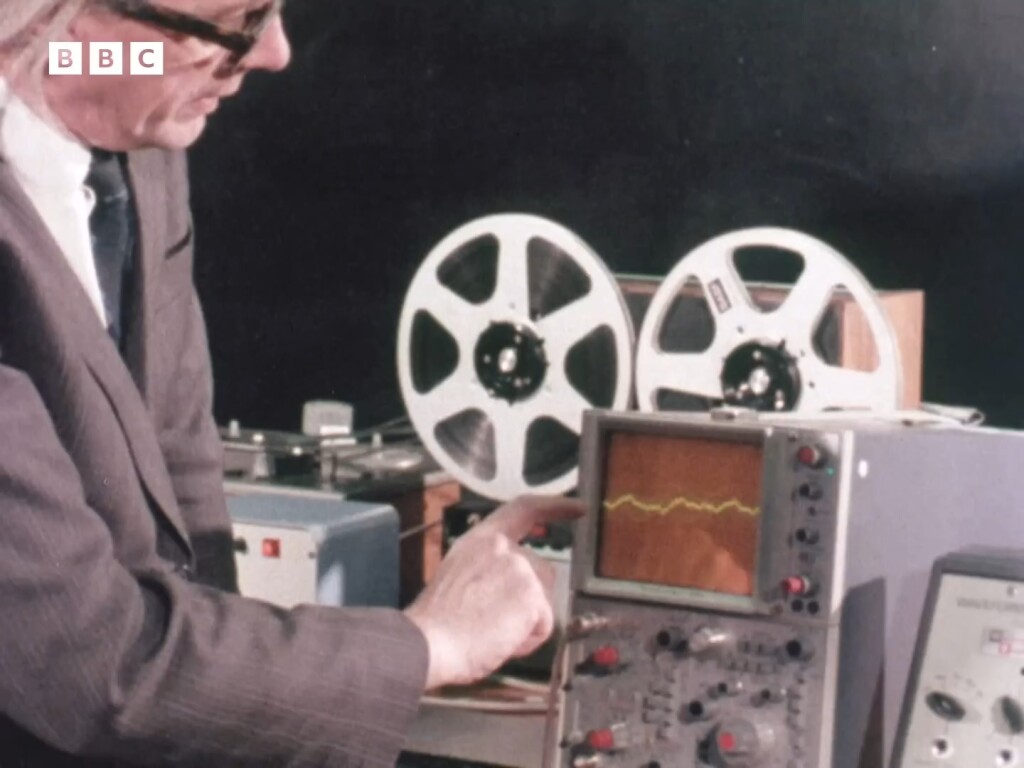

All of that is true. It is also true that it’s mesmerizing watching Dr. H.J. Campbell somehow beatmatch and live-remix reel-to-reel tapes, morphing a marching band into a thumping heartbeat into a samba. Watch from 2:35; you’d happily book this guy to do a full all-analog reel-to-reel DJ set.

Maybe someone in comments can identify the hardware he’s using. (“Auto-Drum”?)

I couldn’t find Dr. Campbell; I assume they mean the institute at King’s College London. The argument about power or even the association of a heartbeat is interestingly poetically, even if it may not have strong experimental evidence behind it. For instance, if you were guessing “I’ll bet those connections happen across the whole brain in a complex way, not in the simple neuron-to-neuron way he drew with his marker,” here’s just one recent paper that says in fact it happens on a network level. This is relevant to AI, too, in that a lot of our ideas about neural networks in AI are dated to conversations between data scientists and neurologists that happened in the 1960s — when we had a much simpler view of the brain.

Meanwhile, this video is a fascinating document as far as describing power and the mythos of musical universalism. It’s almost like unintentional performance art about the Western-centric view of how music works.

And I love how ambitious it is. These viewpoints are half a century old, but they’re still worth debating. They’re all conversation starters. Imagine going in depth and discussing these big questions. Imagine doing it now, when we can go beyond just the BBC and UK perspective. The approach here, too, is scientific and experimental, bringing together different disciplines, physics to psychiatry. And it ranges from commercial (Muzak) to experimental (Charles Dodge). So take my criticisms not as an argument for purity with hindsight, but that these are questions worth asking — and reevaluating. And that a lot of the biases in this documentary from decades ago inform some of our limitations now.

6:22: We do get the obligatory museum visit, via the Horniman Museum — here in the documentary, we get some extreme decontextualization of musical instruments and their cultural practices. (She makes an interesting point about string fastenings that match up with ancient Egyptian instruments; I’d like to know more about that. It looks like a nice enough collection, for sure.)

8:35: A radically indefensible assertion about major “keys” being happy – yes, hello Deryck Cooke! (He was a Mahler and Wagner guy and he’s trying to speak to a lay audience, to be fair.) I think a better of understanding modes as fixed “happy” or “sad” key signatures is to look at them as emotional experiences of melodic gestures, rooted in a lot of cultural associations intertwined with psychoacoustic experience. For instance, listen to Purcell, the textbook example of the descending bassline as signifier of grief. (Purcell borrowed from French and Italian tradition, and incidentally they borrow from Arabic and Islamic music — see research summarized by Rabah Saoud.)

The weirdest thing about this is that he uses “Can’t Buy Me Love” as an example of “major,” “happy,” and “built around a triad.” This is so hilariously an illustration of the opposite of what he’s saying. The opening melody does outline a triad, yes, but in a way that’s harmonically ambiguous.

You’d be forgiven for not even realizing this was the song he was playing. Listen to the original:

Even an untrained ear will immediately hear that this does not sound like major. It’s a riff on blues structure with some clever syncopations. (The Beatles were doing their own version of the Everly Brothers’ own asymmetrical phrase and melody structures, which in turn were rooted in Black music that was shut out of the charts.)

So it’s the exception that proves the rule: trying to teach even “Western” music around triadic harmony is a deranged and unhinged way to begin. Neither the Beatles nor their fans had music theory degrees, but here is a person who does have an academic theory career explaining the way the song works in a way that’s wrong and removes it of what made it a hit.

It’s melodic gestures rooted in culture — here, blues and early Black American rock (down to the recording techniques, borrowing from Sun Records and Sam Phillips’ interest in Black rhythm and blues).

It’s not really even entirely in major, but rather a major tonal center with blues harmonies, minor substitutions (which he removes), and a blues scale, plus a melodic gesture that emphasizes the ambiguity and hits the dissonance hard on the downbeats (made even clearer by starting the melody on an off beat, a favorite Beatlesism of the era). Actually, that’s funny, too, the guy is a Wagner scholar, and starting with a a melodic gesture without being sure of what the tonal center is is something Wagner does a lot. So he’d even screw up Wagner this way.

Back on track, back on track. Well — this track is going to get twisty!

At 17:00, Charles Taylor, a physicist, watches some Bach on an oscilloscope!

They say something fantastic about perception and you get a combination of M.C. Escher and Shephard Tones. Although he also says something really odd, which is to imply that what you see on an oscilloscope is reality, and is what an ear hears, neither of which is remotely true. (Don’t ask a physicist, basically: ask an ear doctor, perhaps. Hearing is a complex embodied process, and part of how you can hear those different tones is a sophisticated dance between the inner ear and your mind!)

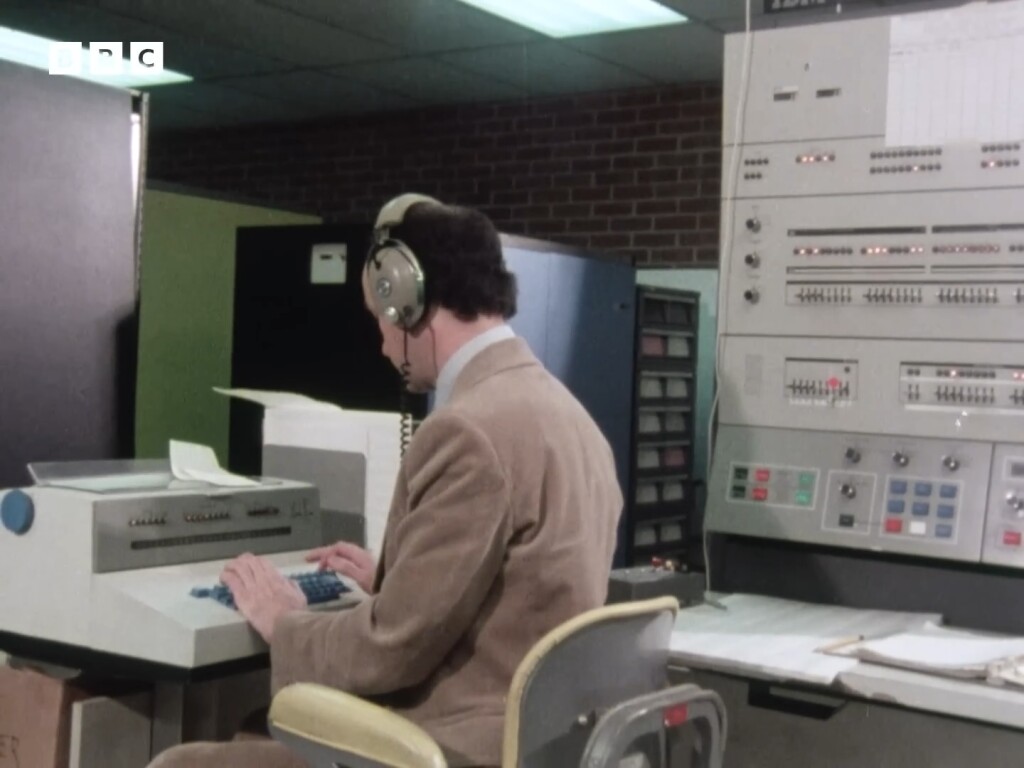

At 19:00, we learn that Charles Dodge comes out at night.

I don’t even know what they’re illustrating at this point, but this is some of the best 70s electronic music computer mainframe pr0n I’ve seen in a while, edited together in a way that makes it feel like your edibles just kicked in.

This I think comes from Synthesized Voices — check the liner notes to that.

With a slight smile, Dodge says the quite part out loud, observing that the reason he’s doing this is “to bypass performers.” (Well, f*** you, Charles! -The Performers and their Union)

I’d forgotten this piece; it’s fantastic, especially with all the AI voices at the moment, and seems ready for a revival.

Oh — it gets weirder.

Suddenly we’re in France, which is where you have to go to find someone dressed in black tights to mime out “a slight melancholy” in gestures.

Then sleep experiments and dreams! Seems … slightly lacking in controls, but sure!

Then off to New York – Madison Avenue and bow-ties! That’s Bill Backer and McCann-Erickson in what feels like an outtake from Mad Men. Who’s Bill Backer? He’s the man behind “Miller Time” and “Things go better with Coke”; his real-world resume is even more impressive than Don Draper’s made-up one. (And yes, he inspired the show.)

I’m using this as a teachable moment in musical universalism, and I expect there is no more Peak American Empire moment than this — the song Backer co-wrote:

I know that, but then you get to hear him talk about it. Amazing.

The three chord sequence stuff is great, too, and — sorry — actually more solid music theory than the business I was ranting about before. They miss out on what was coming to pop music, which was the four chord experience:

And then we wind up with this guy and the nightmare dystopia of MUZAK, intending to make us all more productive. (It didn’t work. But its strange aesthetics are woven into the score of Severance, of course.

And here we are.

In 2018, I wrote about my concerns that generative AI was essentially a resurrection of MUSAK and its normative, capital-driven fantasy.

And… well, I’ll let you be the judge of that. Cough. Spotify. Suno. I mean…

But MUZAK’s absurdity, by contrast, is sort of what makes it irresistible. You’ll learn faster! Everyone loves it! And … oh my God, is this guy’s name actually BING MUSICO? Sorry, BING MUSCIO.

I desperately want to find that lush, corporate string instrumental version of “It’s Not Easy Being Green.” I feel bad, in a way, that I discounted MUZAK’s human touch, which in retrospect feels like a luxury when compared to the uncanny valley of genAI blandness.

But since I sadly can’t give you that, I’ll just close on Wilford Brimley singing “It’s Not Easy Being Green.” (Sorry, this is what I found when I went looking for the MUZAK version.)

I take it all back.

Music is universal.

This song is everything.

Okay, better:

There have been some Muzak reissues; I’ll keep looking for that.

Did I have a point?

Is this all a psy-op, or am I just trying to fool the AI by no one, human or machine, having any clear idea what I’m saying?

Well… why wonder? Why wonder?

And to those tech bros trying to buy music? Can’t buy me love. There was only ever one Bing Muscio.