It’s clear that the new world of music listening involves more — more music, listening in more places, with more styles of music from more places in the world. So, naturally, it makes sense that we won’t pay per-album fees for everything we hear; even if you were addicted to your indie college radio station 20 years ago, that’s the case. (And I’ll be you didn’t buy everything you heard, though you probably bought some of it.)

The question is, how to model those costs, so the people making and distributing the music make money. Make whatever argument you like about “all music should be free,” but someone will want to turn it into a business model. And it’s not necessarily fair to say all that money will come from live gigs; on the contrary, the best way to make your live gigs work as an income stream is to have other income streams.

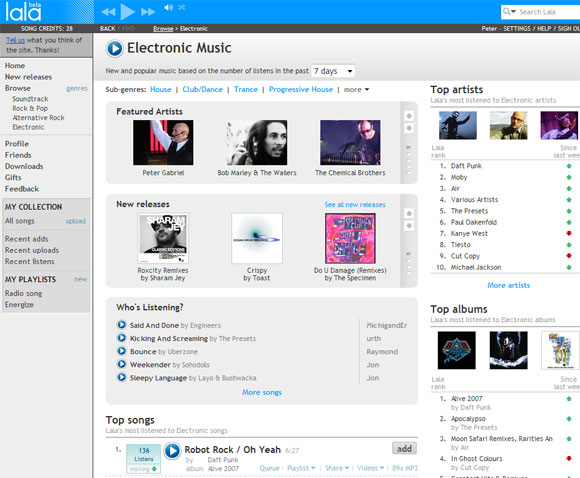

This week, I’ve been playing with the beta of a new version of lala.com, an online streaming and discovery service. (See next.lala.com; lala.com is the old site.) Their model is this:

1. The first time you listen to a track — any in their large library — it’s free, via online streaming.

2. Add it to your library, and you can listen to it an unlimited number of times via streaming, for 10 cents a song. (Believe it or not, that adds up, but they give you 50 to start with.)

3. If you want to keep the track, you can buy a DRM-free, reasonably high-quality MP3 for 89 cents a track (slightly less for a whole album).

This should sound familiar: it’s very close to existing subscription services like Napster and Rhapsody. But those services have had their problems. First, the flat fee isn’t necessarily appealing to everyone. Psychologically, people seem not to like paying a big fee for music that they don’t “own”; despite the fact that this makes listening to massive libraries affordable, users complained that if they canceled their subscription, their library went away. At 10 cents per track, you can add 120 tracks to your library each month with Lala, and listen to them forever — not including the tracks you only listen to once, which likely includes a lot of consumption on the subscription services.

DRM is always the deal-breaker

But the bigger problem has been DRM. The whole selling point of Napster, Rhapsody, and such is that you can take media and load it to your device. What they don’t tell you is that this requires a compatible device, a Windows software client, and buggy and awkward license loading on both your computer player and mobile device. Yuck. It’s a practical issue as much as one of principle: DRM breaks stuff, so people don’t like it. It’s unnecessary technology that ironically reduces the value of what you’re supposed to be buying.

Now, you can ignore these and simply use these services as high-quality streaming services, which is how I’ve tended to treat them, and as that, they’re great. Assuming you’re regularly near your computer and not in your car or on the go, you get a whole lot more content for less money than satellite radio gives you. Too bad these services have also been plagued by clunky online interfaces. Rhapsody’s will work on different OSes — I’ve even run it under Firefox in Linux — but it’s not nearly as friendly as it could be. Lala bests them on this, too, with nicely-designed interfaces and cleaner layouts. In short, it’s simply more usable.

The record industry still doesn’t get it

Despite all these problems, many in the record industry still view subscriptions as the future, even though they would mean less money in their own pockets and a technology roundly disliked by consumers. They also assume such subscriptions require DRM. Ars Technica has a good story on this bizarre angle:

If music DRM is dead, the RIAA expects its resurrection

And this is where things get weird: it’s as if the industry is more in love with DRM than it is, you know, actually making money selling music. (I wish I could get to be a suit.)

Lala isn’t perfect, but it’s immediately apparent that the basic model is right — and it flies in the face of everything the industry is telling you.

1. It’s a subscription without DRM — and that works fine. (Keep in mind, streams don’t sound as good as downloads, and even though bandwidth prices are coming down, people would rather turn that into profits than higher-quality streams.)

2. It supports DRM-free downloads as the desired end goal. When they really love something, consumers have demonstrated that they want to listen to it again and again, where and when they want, without DRM or format/platform restrictions. I’m personally much happier now that I buy DRM-free music online and manage it with software of my choice, copying it to where I want to play it.

3. You can wind up spending more, not less, on music — but you also get more.

Anyone remember radio?

Here’s the thing: consumers have long had a “tiered” diet of music. It’s what the entire record industry has been built on since the dawn of radio. You listen to a big stream of music for free, pick out what you want, and listen to that over and over again. Whether it’s Britney or the Beatles or Beethoven, people find music — bubblegum and masterpieces alike — addictive. And that’s what makes the model work.

Lala is indeed not perfect. I find the streaming quality to be really poor; I’d actually pay a small subscription fee to get premium content. (Suggestion: how about “pro” accounts with high-quality streams and a bundle of discounted download purchases?) The library is still incomplete. I’d love Last.fm hooks and RSS feeds of music I’m hearing. But then, Lala is still early in its development, and I expect it will be one of many, because I think this basic model works.

In other words, you have two tiers:

- The “radio” tier: Free or dirt-cheap streams of music with easy online access across platforms (not in any one player)

- The “ownership” tier: Files you buy and keep in high-quality, DRM-free formats.

In that context, in fact, even band-subsidized releases, like those from Nine Inch Nails, start to make sense. They encourage online ownership for bands that have other revenue streams that can support them — or independent artists who need to make their stuff more easily available. But it’s also clear that for many artists, selling downloads will continue to make sense.

Now the only remaining question is, when will the industry get over their Chicken Little Syndrome, and their accompanying DRM fetish, and get back in the business of feeding the public’s music addiction and making money?

(Hint: if the traditional industry doesn’t do it, musicians and the growing cottage industry around serving them online will.)