Industry titans Google, Amazon, and now Apple have each launched “cloud” music services. Yet, despite being connected via the Internet by design, these services are primarily concerned with solo listening. Even with Google’s various social efforts (+1 and the like), or Apple’s fledgling if not-exactly-blockbuster service Ping, there’s little to suggest that sharing with friends online was even a consideration. All of this raises the question: what should listening look like now that we’re connecting to music through the Internet, instead of through the headphone jack of our Walkman? Against that background, writer Primus Luta (David Dodson) offers a guest editorial on the potential of social music and new means of listening.

I’d like to start this off with a proposal. Despite the incredible innovations that have developed in music in the past few decades, none can match the impact of the one pictured above: the Sony Walkman. To understand my rationale, separate the music from the business. Though the Walkman had a clear impact on the music industry, what it did for the listener’s experience was the seed for most of the innovations that followed.

When I was growing up, the whole idea of personal listening was limited to one’s ability to find a closed room with a stereo system. When you played something, everyone within earshot heard it, be it my mom rocking Olatunji while she cleaned house, my sister bumping David Bowie, or my aunt throwing back to Etta James. I did have a small radio I used to listen to Casey Kasem count down the top 40 in my room, but for the most part, when someone listened to music, everyone did. Outside, boom boxes reigned supreme: you’d hear what someone was blasting as they walked down the block then hit the record store to track it down.

Then came the Walkman, which allowed for private music listening in any environment. There were a lot of benefits to this, not the least of which was my mom not having to hear the 2 Live Crew I was nodding my head to (or even knowing I was listening to it, shhhhh). Over the years, however, this privatization of music listening has led to a decrease in spaces for social listening or even recognizing that listening to music is a social experience.

This piece began with a simple tweet from CDM editor Peter Kirn, in which he made a tongue in cheek reference to music being his favorite anti-social experience. The comment stuck out for me because I’d recently been using two services which sought to restore the meaning of social listening. Both services move away from the networking aspect of the social movement, assuming you already have the network of friends you’d like to listen to music with, and jumping straight into the practical by providing a virtual space where you and those friends can listen to music together.

“As a teenager,” Abe Fettig, the developer behind The Listening Room shares, “it seemed like any time I was with friends, shooting baskets, playing videogames or riding around in someone’s car, there was music playing. So even though I listened to commercial radio a lot back then, I think most of the music I fell in love with came to me via having a friend who owned the album play it for me.

“I had been thinking about how listening to music with other people, and talking about what you’re listening to, is a fun thing to do, and something I wished I could do more,” he shares on the inspiration for The Listening Room. “There’s something about the conversation that makes it more fun than just hearing the song.” Inspired by NPR podcasts of a similar format, Abe and his friend Luke began a blog. “We both listened to a song at the same time, talked about it in real time, and published our chat to the blog.”

For better or for worse the blog wasn’t the biggest success, but the idea behind it stuck with Abe. “Reading about HTML5 audio, and I thought it would be a fun experiment to build an app that would stream an mp3 file from one person’s web browser so another person could hear it in their browser. So I started with that, and immediately felt like I was onto something good.”

Similar thoughts were at play in Denmark, as Esben Milan, one of the developers behind MuMu Player, explains: “I thought about making a live whiteboard where creative people could meet in a online space and draw, write and create projects together. My good friend had a similar idea for an office player where everybody in the office could control the physical speakers.” From this, MuMu Player was born.

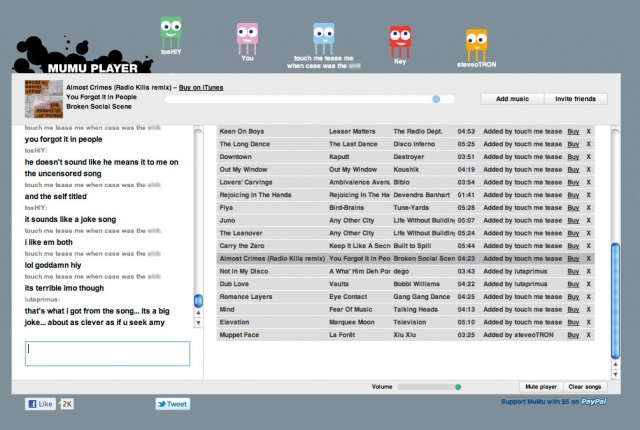

While there are parallels between the two services, the executions and experiences do differ. With MuMu Player, a central playlist layout manages social interaction. “Everybody in the player can upload music and re-arrange the playlist – and the music plays in sync. That’s it. It’s the virtual way of when friends listen to music together in real life.” MuMu Player’s simplicity makes it quite intuitive. The shared playlist shows everyone’s uploads in the order in which they will be played and a side bar area is set aside for chatting while the music plays. One of the biggest differences between the two services is that MuMu is limited to five listeners per room. There are advantages to this, especially when managing the playlist and following conversations in the chat window. Overall, it makes the experience feel very intimate.

The Listening Room abandons the centralized playlist and has no user limit, but because of that, operates a little differently. “Any registered user can create a room and add songs. When a song plays everyone in the room hears it, and sees the record spinning with album art. Any user — even those who haven’t registered — can drop in on a room to listen and chat. The chat is in sync with the music, so as you scroll down the page you can see what people said next to what was playing at the time.” What plays isn’t as immediately intuitive as with MuMu. The shared playlist is replaced with a personal queue of songs which only you can see and rearrange. When multiple users have songs in their queue, the room will alternate between user queues to pull selections. As there are no user limits on an individual room, it takes away the hassle of having to worry about playlist management, though without being able to see what someone has in their queue until it plays it makes the song selection a little less interactive.

Ultimately, though, the thing that makes both services is the ability to converse about music in real time. Not only can you play your friend that song, you can key them in on a specific part of it. Discover the six degrees that separate your interest in shoegaze from your friend’s death metal collection. And how are you supposed to know what minimal witch house is until someone you trust plays it for you?

I wish I could end this piece right here: try them both and see what works for you. Either way, you’ll surely discover the joy true social listening inspires. Unfortunately, though, both of these involve a hot topic of discussion in the IP world — streaming rights. Both services do everything they can to adhere the rules as they exist today, but there’s reason for concern.

“Its a very complex area,” Esben explains. “We believe MuMu is legal, like it is legal for groups of people to listen to music together in real life. Everything in MuMu is also made with that in mind. By example, when a user exits a player his or her’s songs automatically is removed from playlist.”

“The United States has what’s called statutory licensing for ‘non-interactive’ broadcasters,” Abe says. “The statutory license means that you don’t have to negotiate your own deal with the music labels – there are predefined terms available to anyone, as long as your service meets the definition of non-interactive, which basically means the listener doesn’t get to choose exactly what they want to hear on demand (Pandora is non-interactive, for example). So I designed The Listening Room to meet the qualifications for a non-interactive service. And my company pays SoundExchange [an entity that represents labels and artists] as well as BMI, ASCAP, and SESAC [which represent songwriters and publishers] fees for all the music that gets played.”

So far, there have been no legal actions against the services, but considering they are breaking into a new realm of streaming service, how that will hold up is uncertain. That both are aware of the issues bodes for their ability to adjust should things change.

The Listening Room

MuMu Player

Ed.: Do let us know if you try these services, and what you think of the challenges social listening faces, and potential it holds – technological, legal, and personal. I noticed a headline the other day claiming people were using smart phones as quasi-boomboxes, albeit via the internal speaker, but that still seems a poor substitute. Can social listening translate online? -PK