The role of the music score is an important one, as a lingua franca – it puts musical information in a format a lot of people can read. And it does that by adhering to standards.

Now with computers, phones, and tablets all over the planet, can music notation adapt?

A new group is working on bringing digital notation as a standard to the Web. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) – yes, the folks who bring you other Web standards – formed what they’re describing as a “community group” to work on notation.

That doesn’t mean your next Chrome build will give you lead sheets. W3C are hosting, not endorsing the project – not yet. And there’s a lot of work to be done. But many of the necessary players are onboard, which could mean some musically useful progress.

The news arrived in my inbox by way of Hamburg-based Steinberg. That’s no surprise; we knew back in 2013 that the core team behind Sibelius had arrived at Steinberg after a reorganization at Avid pushed them out of the company they original started.

The other big player in the group is MakeMusic, developers of Finale. And they’re not mincing words: they’re transferring the ownership of the MusicXML interchange format to the new, open group:

MakeMusic Transfers MusicXML Development to W3C [musicxml.com]

The next step: make notation work on the Web. Sibelius were, while not the first to put notation on the Web, the first to popularize online sharing as a headline feature in a mainstream notation tool. Sibelius even had a platform for sharing and selling scores, complete with music playback. But that was dependent on a proprietary plug-in – now, the browser is finally catching up, and we can do all of the things Scorch does right in browser.

So, it’s time for an open standard. And the basic foundation already exists. The new W3C Music Notation Community Group promises to “maintain and update” two existing standards – MusicXML and the awkwardly-acronym’ed SMuFL (Standard Music Font Layout). Smuffle sounds like a Muppet from Sesame Street, but okay.

These are two important pieces of the puzzle.

MusicXML is a standard format for describing the entire score in a way that can be exchanged. It’s supported by 200 applications already; it’d be terrific to see native support in browser like Chrome and Firefox and Safari. Currently, the format is managed by MakeMusic and its VP of Research and Development — the original creator, Michael Good. MakeMusic acquired the technology along with Recordare, who built support for other apps. Unlike some acquisitions, cough, they’ve since expanded, not contracted, support and compatibility.

SMuFL helps you standardize which symbols get mapped to codes and how they’re added to a score – so that specialized (Western) music symbols show up correctly. (You want the right code, and you want it to show up in the right place on the score!) SMuFL was introduced by Daniel Spreadbury (he’s now at Steinberg) in 2013, but it’s also set to be built into a coming version of Finale. Basically, the idea is to expand upon the woefully inadequate mappings in Unicode to cover the sorts of symbols people working with scores use every day.

And that’s what this is all about: the notation software business benefits from more compatibility. The easier it is to share scores, the more people make scores, and the more they can use notation tools. Accordingly, the group will be co-chaired by Michael Good, Steinberg’s Daniel Spreadbury, and Noteflight’s Joe Berkovitz. Significantly, Mr. Berkovitz also chairs the W3C Audio group that’s been moving along in-browser sound. That puts the whole initiative in very capable hands.

Also, because Noteflight is owned by Hal Leonard, that leading digital and print publisher of scores is also involved.

That said, there’s room to look more broadly. I will put on my academic hat and strongly urge the W3C community group to consider an expanded music notational language for the Web covering non-Western notational systems. Graphic notation (as in experimental composition) is perhaps best described simply with existing open-ended graphic languages, but there are some extended notational systems in common use in such a way that they could be standardized. Music notation standards also should consider a non-Western perspective. The proposal to me calls out for a third “puzzle piece” specification, and actually the Web would be an ideal place to experiment, as it’s nearly universally accessible and not bound by the kinds of economies of development, marketing, resale, and support that restrict monolithic notation programs like Finale or Sibelius.

I’m also concerned that so far the people developing the standard represent only technologists selling music software and don’t yet include input from the realms of music theory and musicology. Desktop publishing worked because of rich input from people who worked directly with traditional typography and design; color formulations require an understanding of how color is used outside only how it is reproduced.

Fortunately, this is project features an open call.

Find out more about the group:

https://www.w3.org/community/music-notation/

Read Michael’s excellent opening story on how these projects evolved and what the group intends to do:

He talks specifically about expanding interactive and Web possibilities, starting with updating these existing formats. And that could reach a lot of people:

Introducing the Music Notation Community Group

The group aims to serve a broad range of users engaging in music-related activities involving notation. These users include, among others, software developers, music publishers, composers, performers, students, listeners, scholars and librarians. Some of the activities covered include composing, arranging, preparing, performing, teaching, learning, studying, and enjoying notated music.

Call for Participation in Music Notation Community Group

This seems to me a promising start, and putting this on the Web could more easily invite just that sort of input.

If the Web is about sharing ideas, the ability to share scores, to be able to communicate intentions to other musicians, must surely be fundamental. Our browser may still be catching up with what paper could do in the 19th Century. But this could be the beginning of 21st century notation, too.

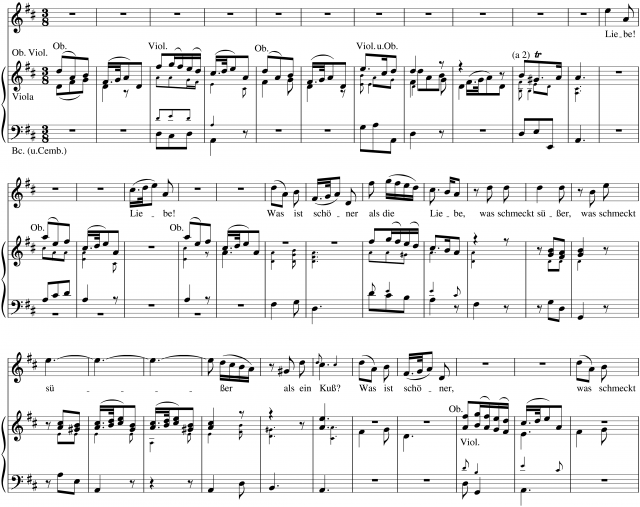

At top: an example of what you can do with MusicXML.