For a long time, technologists have described a world of in which computing experiences naturally incorporate touch and gesture. The question is, how do we bridge the intuitive desire for those interactions and the actual technologies that get us there?

Few activities test the expressive potential of interaction quite like music. It’s in our cultural DNA; musical activity may even predate written language. So it’s fitting that the story of touch in computing and digital music would be intertwined, as they are with touch pioneer JazzMutant. Years before well-known Apple products, the Lemur, prototyped in 2003 and shown as a musical multi-touch screen, suggested the importance of fusing display and touch, and of tracking more than a finger or two at a time.

The history, and products like Apple’s iPad and iPhone, you may know well, though. The question on everyone’s mind now is, what’s next? (And for some impatient futurists, the question may even be, what’s taking so long?)

To begin to answer that question, I turned to Guillaume Largillier, original co-founder and CEO of JazzMutant, now Stantum Technologies. There aren’t many people on the planet closer to where touch has been and where it might be going. Even as the Lemur gets new features like integration with popular music production and performance tool Ableton Live, Stantum is working to bring the same enabling technologies to other device makers. And even though this is “Create Digital Music,” it’s telling that that technology is showing potential in everything from phones to aviation, not just DJing. Musicians have had a role in technological history before, from Leon Theremin’s work to Max Mathews and computer synthesis. It may be musicians who invent the future, again. This time, the trick is who delivers that future to the hardware makers who can popularize it.

http://jazzmutant.com/

http://jazzmutant.com/behindthelemur.php

http://www.stantum.com/en/

http://www.stantum.com/en/offer/technology-ip

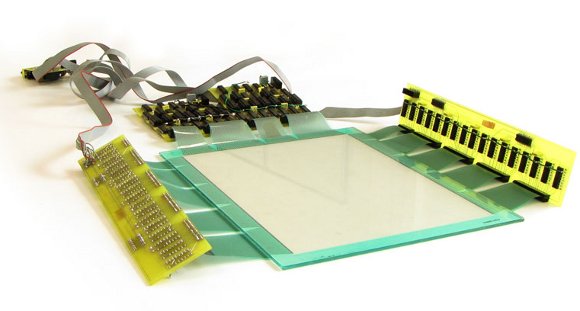

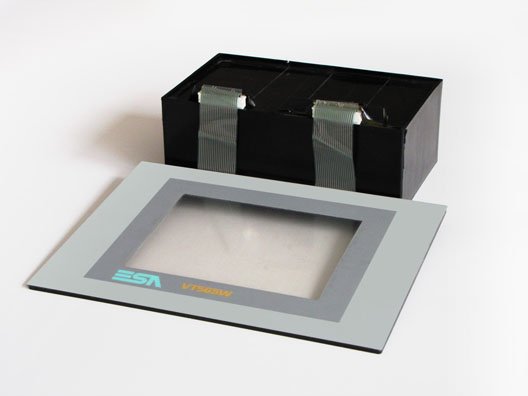

To accompany the story, we also have an exclusive look inside Stantum’s labs, all the way back to the original 2003 prototype of the Lemur.

On Designing for Touch, and the Music Tech Industry

Peter: I remember when I first talked to Darwin Grosse about Lemur, when it was being distributed by Cycling ’74. Darwin just kept saying, “You know, I just think Star Trek: The Next Generation.” (That’s my recollection, Darwin; I hope I’m not misquoting you.) I tended to agree. It’s a cliche, perhaps, but this was clearly hardware that brought into our century part of an imagined vision of a much further-off future (the 24th Century). Was that a conscious influence? In an industry that has sometimes been aggressively traditional, is there a way to channel ideas from something as far out as science fiction?

Guillaume: Before answering your question, allow me to challenge your statement about the computer music industry. I think “ill nostalgic” would describe this industry much better than “aggresively traditional.” Most music software companies have kept being innovative over the last decade, but their creativity has been a slave to this nostalgic obsession. Emulating an analog channel strip, a tube amplifier, or a vintage synth is far from a trivial job. It actually requires as much engineering time and resources as developing a disruptive product such as Ableton Live or Max/MSP/Jitter! On the hardware side, the innovation killer is the price pressure. Despite a common misconception, the computer music industry is not and will never be a mass market. Companies such as M-Audio [Avid], Behringer, or Native Instruments may look like giants compared to JazzMutant, but they are nano-particles compared to large consumer electronic brands such as HP or Nokia. The volume and the gross margins are too small to amortize ambitious research and development plans. When we launched the Lemur in 2005, a lot of people predicted, and somewhat hoped, that Behringer would release a similar device at $200 within the next eighteen months. Five years later, the first serious competitor of the Lemur is about to land – Apple’s iPad – and its entry level price is $500.

Back to the USS Enterprise, whether we want it or not, this parentship is likely to follow the Lemur forever. This is kind of ironic insofar as I’ve never been acquainted with science-fiction culture. I don’t even remember having ever watched a full episode of Star Trek. That being said, I acknowledge that this association has settled spontaneously and durably in people’s mind. Does this association come from the product concept itself? I don’t think so. In my opinion, it comes first and foremost from the fluorescent graphic design of the UI objects, not from the tactile technology.

So, the real question would rather be: “Why did we design the graphic interface this way?” First, we wanted to stand clear of those boring pseudo-vintage brushed-aluminium graphic skins – the cutaneous symptom of the nostalgic flu! Moreover, we anticipated that converting users to virtual controllers would be a difficult task and that trying to mimic the appearance of real-life objects would generate frustration; hence, impeding the adoption of the product.

Having said that, the main purpose of this flashy design was pragmatic and ergonomic. The Lemur is ontologically a live controller, though it might be used in other contexts. This requires that the interface must be visible wherever and whenever a user might be performing, from night clubs to outdoor venues. This is particularly tricky with a touch screen laid horizontally, because the display backlight cannot compete with the specular reflection of sunlight. Human-factor sciences taught us that contrast perception prevails over brightness perception. Hence, highly contrasted graphics- ie, flashy objects on dark background – is the most efficient way to ensure a consistent readability. This is something the aerospace industry has understood for decades. So, if there was one conscious influence behind the Lemur, it would be the Boeing 747 dashboard, not the USS Enterprise.

“If there was one conscious influence behind the Lemur, it would be the Boeing 747 dashboard, not the USS Enterprise.”

I know for me, the appeal of the science fiction aspect was more conceptual than superficial, the idea of the ubiquitous touch interface. But I agree, having experimented with this, that the high contrast, light foreground, dark background formula is really an essential solution. I’m seeing some interfaces on a white background that look aeshtetically lovely, but that I can’t imagine using onstage. I’d at least want a switch for dark environments, when you’re not at your desk.

That reminds me a funny episode of JazzMutant’s story. As early as February 2004, we started showing early prototypes of the Lemur to our friends at [Paris sound research center] IRCAM. At this time, the graphic skin was based on a palette of blue shades, with a few touches of warm yellow for emphasizing elements that needed to stand out, such as text, levels, etc. One day in July of 2004, about one year before the commercial launch of the product, we brought them a new prototype, featuring a brand new touch panel along with the final graphic design. Their only reaction was, “wow, this display is much brighter!” They did not even comment on the tremendeous improvement to the touch panel! That being said, there are other approaches to improve the psychological perception of readibility. I sometimes regret that other developpers are reluctant to dig into them, and mimic the “Lemur style” instead.

Talking about drawing on screen, did you know that Iannis Xenakis’ Upic project has been my main source of inspiration – and also my main motivation to step from music making to technology creation ?

I didn’t know that, but it makes a lot of sense. [UPIC is a tablet-based, visual composition system developed by ground-breaking experimental composer Xenakis. It is now decades old but continues to evolve in new incarnations.]

Below: DJ Mike Relm demonstrates the Lemur for G4 Tech TV. Yes, this is the video to show all your friends who aren’t regular CDM readers and have no idea what the heck this is all about.

Lessons of Lemur

Let’s talk about the place of Lemur’s technology in the current landscape. How does it hold up in 2010? I know a lot of people do get hung up on the price, but can you talk about how it differs from other options out there, or what the source of the cost is?

Once again, the music market being a small niche, it’s hardly possible to be both innovative and affordable at once. In addition, the Lemur is still manufactured in France with components imported from various locations around the globe – not to mention that the US dollar’s agony doesn’t help [when exporting] the manufactured product! Lastly, a large part of the product assembly is still handcrafted. For all the reasons above, the product is far from cost-optimized. I cannot disclose further our plans now, but we are working hard to address most – if not all – of these issues.

Have there been uses of the Lemur in performance and creation that surprised you, or went beyond what you imagined?

Oddely enough, and despite of what I said before, the most surprising uses of the Lemur are sometimes the most conservative ones! As an example, for Björk Volta tour, Damian Taylor and LFO made the most archaic interface layouts one could imagine — a fistful of colored labelled pads and eventually a pair of faders –- nothing more. Their brilliant idea was to create one unique interface for each song. This way, at each moment of the gig, they just had at their disposal the few commands they did actually need. The other big surprise came from video performers. Whereas most musicians are reluctant to use the advanced features of the lemur during their live performances – such as the objects’ physics – video artists do not hesitate to play the Lemur as an instrument, rather than a remote control. For instance, I warmly recommand you to visit Ali Momeni’s website. Of course, it would be unfair to forget all the advanced users who have developed inspiring and unique instruments, but this is less surprising, since the Lemur was designed specifically for that purpose.

OSC is a technology that many of us have advocated, but there’s also, admittedly, a big gap between where we believe it could be and where it is, especially in regards to the lack of mainstream music tech adoption. That said, what would an ideal implementation of OSC look like? What could the protocol do to be better? And what might you imagine could be a tipping point in adoption?

Indeed, it’s fair to say that OSC failed to become the industry standard we hoped it will be! I can see a few reasons for that. First, there is an obvious chicken-and-egg issue, as with any protocol. At JazzMutant, we’ve done our best to evangelize OSC in the industry for about 5 years now, without success. Why should a software company implement OSC if there is no hardware to support it, apart from a $2k product? Why should a hardware manufacturer develop an OSC-compatible controller if there are no mainstream applications to support it? Finally, there are also some intrinsic technical reasons that prevent OSC from becoming a standard anytime soon. In order to overcome them, we started developing a new protocol a few years ago called “Minuit” (“Midnight” in French), as a successor to OSC and MIDI (“Noon” in French). We were discouraged from pursuing this project after assessing the amount of human resources its evangelization would require.

The Big Picture, Stantum, and the Future

We’re looking at an explosion of interest in multi-touch display surfaces in the consumer space. Are any of these, in your view, promising for music? Are there ways in which some of these technologies are deficient for musical performance applications?

The responsiveness of a touch system is the most under-estimated parameter, even though it tremendously influences the perceived usability, transparency and trustworthiness of an input device. This is why a vast majority of Multi-touch systems available fails to meet music makers’ expectations.

Absolutely — you mean responsiveness in terms of latency, accuracy, precision in tracking multiple points, or (I presume) all of the above?

I was pointing out the latency more specifically – even though the perceived responsiveness is a complexe imbrication of all these parameters.

Can you talk about Stantum’s role in the evolution of multi-touch? What can we expect to see in the future?

We envisioned the real potential of the technology we invented long before the iPhone announcement, though we could not imagine that Steve Jobs’ crew would accelerate the market demand [to the extent they did]. We started investigating how we could bring our technology to OEMs in parallel to our computer music activity as early as 2005. We finally made this step in 2007. The role of Stantum in this ecosystem is quite singular. However pretentious it may sound to you, Stantum is still the only company beside Apple to have developped a real multi-touch product, top-down, including all the software and hardware technology bricks. So, despite the small size of our company, we are better placed than any other player in this field to understand the complexe imbrication of software and hardware. You might ask, “Aren’t all these Windows 7 convertible notebooks real multi-touch products?” In my opinion, they are not, insofar as the only multi-touch services these devices offer so far are rotating videos or ten-finger painting. I do not want to offend anyone, but watching videos is much more pleasant fullscreen and if Neanderthal people gave up painting with ten fingers 45,000 years ago, there might be a good reason. At JazzMutant/Stantum, we’ve always considered the multi-touch technology as a milestone, not the final destination. With what we’ve been incubating in our labs for a few months, we expect to reach the next big milestone quite soon.

Do you mean that these PC vendors are missing the actual application of the multi-touch technology in the software they ship with these devices? Certainly, no argument there — the demos, the marketing, the demo apps outside of Apple have just looked horrendous and awful to me. But surely there are developers out there who want to do better? Hasn’t what’s held them back simply the lack of available hardware?

I do agree with you. Unfortunately, that leads to a chicken-and-egg situation; insofar as developing a meaningful, multi-touch-capable application requires a preliminary awareness of the objective capabilities and limitations of a given hardware solution. On the other side, a vast majority of multi-touch panel providers doesn’t look willing to raise the bar until the market identifies a “killer app” requiring full multi-touch capabilities with zero performance tradeoff. Hopefully, the iPad will contribute to reschuffle the cards. Unfortunately, Apple decided to stand clear of handwriting capability – which, I believe, is a huge limitation for creative and productive applications.

“I do not want to offend anyone, but … if Neanderthal people gave up painting with ten fingers 45,000 years ago, there might be a good reason.”

Let’s assume Stantum is successful in popularizing the technology. At some point, will the Lemur be obsolete – and could that perhaps even be a good goal?

The Lemur as it is today is likely to become obsolete at some point – the pet is more than 5 years old in an industry that usually sends hardware products to retirement manu militari at 18 month old! Having said that, there is much more to develop on the hardware side than what we have done in the past. If we succeed in what we are working on today, I believe the Lemur will keep playing in its own category for quite a long while.

Now, that said, how do Stantum’s efforts to engage the larger electronics industry impact these issues of scale and cost?

We understood as early as 2005 that there was only one path to spread this technology – and the underlying vision of how computerized equipments should work – out of the small niche of professional musicians and Max/MSP users. Then we did what we had to do : we licensed the technology to tier-one semi-conductor companies such as ST Microelectronics to embed our multi-touch know-how into dedicated chips. We also teamed up with some of the largest and most trusted touch panel makers to bring our solution onto the consumer market place. The whole supply chain is now in place and you’re likely to see a few Stantum-based multi-touch tablets shipping in the coming months. Will these products match musicians’ expectation ? That’s too early to risk an answer at this stage, since we have no control over what OEMs will make out of our technology. And as you know, a good user experience does not only depend on the quality of the touch system – it’s also a matter of CPU and OS choice, hardware optimization, not to mention the software application running on top of it. That’s why we believe there’s still some room for a dedicated hardware that takes in consideration the very specific needs of electronic musicians and visual artists. In a not-too-far future, we expect the hard work we have done with our partners will have a positive impact on the cost structure of our music products.

Stantum’s Latest Technology, and What it Means

Guillaume is a bit limited in what he can say about his future plans, but that leaves me free to do a bit of (informed) speculation. This is largely my own analysis, so it’s my message, not necessarily Stantum’s.

First, unless it isn’t already clear, JazzMutant is Stantum. Stantum is JazzMutant. Stantum is now the official name of the company, and JazzMutant is just the brand by which their technology caters to musicians. It says something about the company’s lineage – all the founders have a background in electronic music – that they have in the past, continue now, and plan in the future to keep a strong connection to musicians. That’s meant that the rigorous demands of live music have informed their touch technology and made it a better product.

The idea that Apple’s iPad would drive JazzMutant out of business, therefore, is the opposite of correct. JazzMutant is Stantum. Stantum is in the business of licensing its specialization to OEMs. The Lemur shows just how potent that specialization is, in a way that literally gets rooms full of people dancing and gaping at projections. Apple’s technology is available only to Apple. With Microsoft, Google, phone vendors, and PC vendors all getting into the touch business, that means Stantum just became very big news – even if that’s something musicians and VJs figured out years earlier.

Part of the challenge of multi-touch development is that you have to get a lot of pieces working together. You need the physical surface of the controller, the sensors built into that surface, and the firmware that interprets the sensors all to work in tandem. Apple does it, and does the OS and applications, too. 3M is working on a product for OEMs, also working with multiple touch points. But the other big source right now is Stantum.

It’s also significant that Stantum’s technologies are heavily patented (a fact that they advertise on their site). While I’m no big fan of patents, unlike Apple, Stantum is licensing their technology into the marketplace. Given the need to have a patent portfolio just to protect your work, Stantum’s patents give it effectively the right to play ball. By licensing their technology to the manufacturers big enough to make this stuff on a grand scale, Stantum’s OEM program could provide ready access to touch for software developers beyond just the iPad platform. Even if you’re a huge iPad fan, that means greater accessibility in the market, and more than one vendor to provide that access. I’m a great advocate for DIY, but making displays isn’t yet a garage operation. (Yes, I know people building their own multi-touch tables, but they don’t make their own cameras or projectors.)

Stantum’s technology itself is also unique. Their sensing approach supports pen input and even handwriting recognition, features Apple leaves out. For many of the world’s languages, handwriting recognition is a “killer app,” which could further drive touch adoption. For the rest of us, until we evolve smaller fingers, the ability to use a pen can mean amplified accuracy for painting and writing, and yes, even pen-driven music applications. (Somewhere in the great beyond, Xenakis smiles.)

This is not an advertisement for Stantum, either – the list of companies anywhere close to being able to provide this functionality is short enough to count on your (ahem) fingertips.

So, okay, you buy into the concept – when can you get it? (After all, even the Lemur doesn’t quite count. It isn’t set up for pen input, even if its sensing method could work. And the Lemur is a controller, not a computer.)

Right now, Stantum’s technology is available in a series of multi-touch demonstration kits, including one with the guts of a Dell netbook inside:

http://www.stantum.com/en/offer/evaluate

In other words, we’re waiting for someone to ship a product that incorporates their technology. Windows 7 already includes multi-touch APIs out of the box in all but its Starter edition, so the Windows platform is a major candidate. Windows, while proprietary, has none of the developer, language, software, or hardware restrictions that the iPad platform does, so if your application doesn’t fit the iPad model or needs pen input, Windows’ stock just rose. Free software is possible too. Linux already supports the Stantum Slate PC and a number of other digitizers, support that will be baked into the kernels shipping in this year’s major Linux distros. We’re not just talking drivers, either: the whole Linux community is working on everything from libraries for environments like Java to support in the windowing system to touch-centric distros. (More on the Linux situation later this week.) Google’s Android has a multitouch API, too. I’ve used it, and got frustrated quickly not because of the OS, but because the hardware on current phone handsets just doesn’t work well with more than one finger. That could change if Stantum’s tech starts to appear in licensee products; Android as a touch OS could take off.

For specifics on the Windows 7 aspect (old news, from way back in November – but of course, everyone is taking a second look because of the iPad phenomenon):

2009-11-03 Windows 7 Certification

Right now, the one thing Stantum doesn’t have a lot of – aside from OEMs shipping their tech – is competition. Most of the other touch competitors either can’t accurately track fingers in close proximity, or limit tracking to two fingers, or lose tracking fidelity around the edges of the screen, or can’t handle pens, or some combination.

You need musicians, creative artists, and gamers to tell you this, because the mainstream computer market thinks multi-touch has something to do with pinch-zooming their photos. If that were all you could do with multi-touch, this would indeed be an over-hyped technology. But the responsiveness of the Lemur and the demonstration technology from Stantum is something that can be powerful and expressive.

Apple has already brilliantly demonstrated what happens when scale, creativity, and technical competence meet. Now the question is, who else will be able to put this formula together, thus making other options available to developers? Stantum has the competence, and the connection to creative artists and music specifically. If OEMs start to sign on with Stantum’s tech and build useful hardware, we could see both off-the-shelf machines – and cheaper JazzMutant-branded products – for musicians. Indeed, with this larger Stantum perspective, whatever happens with OEMs could in turn be good for JazzMutant-specific, music-specific customers, too. Even with competition from the likes of 3M, the technology is so specific to certain hardware devices, and the emerging markets so large, it’s hard to imagine Stantum not having a big role.

What might surprise people in the larger tech world is how important music has been – and will continue to be – to the big picture.

When it all comes together, the days of computer musicians, DJs, and visualists standing behind screens, able only to stare blankly into them but unable to manipulate what they see directly, could become a relic of the past.