Before diving into the litany of gripes from artists regarding Apple’s Ping social service, it’s worth saying: some critics say they expected better. Many artists want a smarter, more social iTunes. That’s the only reason anyone is spending time talking about the service’s perceived flaws.

Cellist and laptop musician Zoë Keating, an independent artist with collaborations from Imogen Heap to DJ Shadow, reminded me of that via Twitter. Even amidst her own criticisms, she was quick to add:

“But it’s Apple, so good or bad we all want to be invited to the party!”

That sums up not only the most disappointing aspects of Ping, but also why anyone would care in the first place. This isn’t the age of the hit parade, of Ed Sullivan, or even MTV. It’s the era of the Web, and people expect music media to be genuinely participatory. Because of the popularity of iTunes, the introduction of Ping seemed to artists like an opportunity.

Apple has responded to criticism, addressing some user concerns: Forbes’ Philip Elmer-DeWitt, asking “Can Ping be Saved?” last week, updated his article to reflect that issues with spam and forward and back navigation were fixed over the weekend.

The problem is that the fundamental complaints – and those of artists – run deeper. They may or may not be fixable.

Every artist I talked to said the same thing: the problem with Ping is that you’re not invited to the party. Missing from the guest list: independent (or, indeed, almost any) artists, alternative music stores, iTunes listening data, musical genres, and, above all, the World Wide Web.

Artists can’t make their own pages; Apple invites artists. In May, I criticized analysts for describing the iTunes App Store as being curated, a term I felt didn’t fit. This, on the other hand, really is curation: Apple invites a small number of artists at their discretion, which is why Ping makes some curious recommendations. As Keating puts it, “I’ve never bought Lady Gaga or anything remotely similar, but she is the #1 recommendation and I have to see her everytime I log on. That goes for Katy Perry too…I’ve created a world where I can pretend she doesn’t exist, but Apple really wants me to listen to her.”

Here, there’s a perfect contrast between Apple design and Apple curation. Apple design is beloved in the musical community, for the reliability and attention to detail of their hardware, operating system, and software. But Apple as curator, as tastemaker, is another matter. Apple’s (or Jobs’) obsession with artists like John Mayer had been a punchline, not a source of inspiration. For that matter, why should your computer vendor be responsible for musical taste? Would you ask Microsoft what clothes to wear today?

Apple ignores other music sources. When iTunes is criticized for promoting “lock-in” to Apple’s music store, listeners often respond that they rely on other sources for music. Apple may command big statistics when it comes to online sales, but that’s an aggregate of all music styles. For independent artists, everything from free distribution to specialized online stores – and physical CDs, which still rake in billions of dollars in sales annually – can matter more than iTunes.

Here, Apple runs into the tension between iTunes the player and iTunes the store. Ping as an add-on to iTunes the store makes some sense. As a modest feature that tells you what other iTunes shoppers are buying, it’d be unremarkable but also reasonably uncontroversial, at least before Apple hyped it as a new social network.

But iTunes the player demands higher expectations. iTunes is, for many, the virtual jukebox that the tool was when it began its life, before the debut of the integrated music store or even the iPod. I’ve even talked to frequent iTunes users, people who buy a lot of music, who have only purchased tracks from Apple a couple of times. For nearly anyone, iTunes – and by extension, Ping – must catalog all their musical activities, not just stuff they bought from Apple.

Ping is dumber about iTunes data than non-Apple services. Leaving other music stores out of the picture is perhaps unsurprising. But leaving out iTunes itself is more of a puzzler. The beauty of services like Last.fm is their ability to collect data about yourself that you can use. Sharing that data should obviously be a choice, but as Last.fm has demonstrated, the information can be useful to yourself, to fellow listeners, and to artists. It can make sure you see a favorite artist live or discover musicians based on human interactions, without violating privacy. But Ping is an inferior tool for iTunes data, compared to a third-party service like Last.fm. Wiley Wiggins, an Austin-based visual artist, has an extended complaint about Ping.

The killer insight: Ping is “store-centric,” not “user-centric,” says Wiggins. Flaws in genre handling and awkward mechanisms for tracking music and friends “make Ping seem like it is currently designed for users who 1) do not listen to much music, and 2) do not have many friends.”

Ping Feedback Form [Wiley Wiggins Blog]

Apple’s curatorial tendencies don’t make for a social network. Keating argues some of the tension here is philosophical: “Good social networking is chaotic and grassroots,” she says. “Apple is all about top-down control. Not sure this blend of the two works.”

And then there are … the genres. Aside from limiting you, comically, to choosing three genres you like, Apple seems to have lifted its genre categories from a BMG Music Club sign-up form.

It’s all too broken to be social. User interface trainwrecks, hidden “like” buttons, a “lonely” scene devoid of users or artist pages, and a laborious process to add friends made worse by Apple’s row with Facebook mean that getting anything social going is a waste of time. Mario Anima, who has led community efforts for Current and Community Speak Up! sums up the problems in an excellent post. Even with some navigational tweaks, there just isn’t much in the design that works. Even with Apple’s user base, I that could spell doom for the service. If users don’t spend time, the whole thing becomes pretty useless to artists, who are already fatigued by the amount of heavy lifting they have to do to get noticed online as it is. (See more on that below.)

Apple ignores the Web. Wired Magazine infamously ran an inflammatory cover this summer claiming The Web is Dead. That article could have been written about Ping. Ping isn’t visible on a browser; click on a link to a Ping profile, and it looks for an iTunes 10 client. Ping isn’t searchable. Ping is completely disconnected, at least for now, from the rest of the world – no integration with other services, and no public API. (One developer source told me an API is coming, with extensions to be approved by Apple, but I can’t yet confirm that, and that’d still fall short of making this a Web app.)

Ping is more than a walled garden: it’s a room with no windows or doors. It’s a tomb.

If Ping were the future, the Web might be dead – but early indications are that the reality is just the opposite. (Among many retorts to Wired’s “Web is Dead” thesis, The New York Observer is spot-on, and Boing Boing negates the graph they use to open the story, which turns out to say the opposite of what they claim.)

In fact, if anything, the negative reaction to Ping proves that the Web is more important now than ever before. People expect open participation, they expect browser-based interfaces (at least as an option), and they expect open interoperability and data portability in some form.

Browsers and links matter. Even Twitter and Facebook are popular partly as ways of linking back to other sites – I know this personally, because they’re two of this site’s biggest referrers. The Web make these services publicly searchable, connected, and accessible anywhere. They are the Web, and they also make the rest of the Web even more popular. Apple’s iPad and iPhone may focus more on “apps” than the “browser,” for now, but that singular example hasn’t yet been proven elsewhere. Meanwhile, competing browser-based music services have done just fine without an iTunes client.

Oh, yeah – and don’t forget that the lack of an open API also means hackers are shut out. This past weekend, Music Hackday – which I’ll cover separately – again gathered hordes of geeks to create new musical tools. That included things you’ll never see on Ping, like MixCloud on iPad.

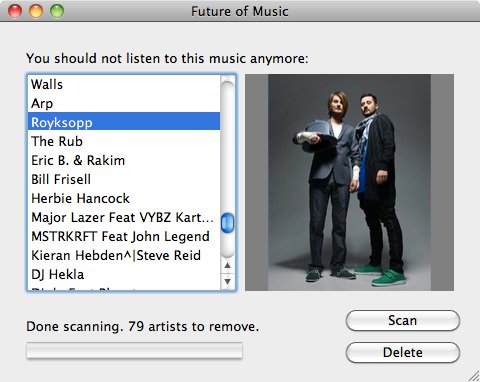

Best of all: Brian Whitman of The Echo Nest had a pithy answer to how recommendation services should work. He created The Future of Music, which tells you which music you shouldn’t listen to. And that brings us to the last point:

In the end, maybe recommendation services aren’t everything. Whitman has a strong argument as he describes his tool:

I have a strong aversion to music recommenders and music similarity services. I especially deal with a lot of cognitive dissonance as the company I co-founded makes a lot of $$$$$ (that is 5 dollar signs) selling ordered lists of artists to multinational music streaming conglomerates.

Nonetheless, we recently completed our first live recommender system (to be announced near the Boston Music Hack day in October) and to perhaps get myself more comfortable with a future in which children will no longer ask their cooler older dope-smoking brothers what to listen to in lieu of some HTML table in a UL, I decided to really sign up wholesale to this movement. If we rely on these computer programs to learn about music, well we might as well rely on them to fix the sins of our past and delete the crap we are obviously not meant to listen to anymore.“Future of Music (2010)” is a Mac OS X app that scans your iTunes library and computes the music you are not supposed to listen to anymore based on your preferences. It then helpfully deletes it from iTunes and your hard drive. Skips the recycle bin.

I don’t think Future of Music will have one million users any time soon. But it does raise the most important point: the actual music has to come first.

Whether or not the general public is fatigued of social networks promising to revolutionize music, you can bet musicians are. Oliver Chesler is the blogger behind “wire to the ear” and, as The Horrorist,” an electronic musician who has topped German charts. He sums it up best:

As a musician the word to describe how I feel about the new Apple Ping social network is: exhausted. Musicians have become the tech industries guinea pigs. Why not? We try anything and work cheap right? After creating and curating profiles on MySpace, Last.fm, Imeem, Facebook and then Facebook Fan Pages and on and on now it’s time for Ping.

For his part, Chesler says he’ll make his own Ping page and promote it, even as “the Lady Gaga’s get all the love.”

Remember why we were all excited about the Internet for music in the first place? It’s a chaotic, level playing field. That can be scary, but given the miraculous, mind-boggling diversity of musical output and taste on planet Earth, it’s perfectly natural. And any business model around music must be built around that reality.

Don’t believe me? Ping may have one million members, but the fastest-growing musical sensation right now is a guy who came to his sister’s aid in an attempted rape and was AutoTuned into… actually, that’s a long story, told neatly by the New York Times. (I couldn’t wrap my head around it at first, either.)

Take a look at his fans. The guy is, literally, a rockstar. How did he get big? He spread on the Web – not on apps, not in any “curated,” walled garden vertically integrated experience. Not in any way, frankly, that makes any logical sense at all. (AttemptedYou know … on the Web.

My guess is, you’ll know Ping (or a competing service) has been fixed when you find Antoine Dodson’s profile. Antoine, if you have music recommendations, we’d love to hear them.

Magic Bonus Addendum!

Broken Social Scene references that fit iTunes Ping! (thanks to the story above)

“Broken Social Scene”

“You Forgot It In People” (or, at least, you forgot people in it)

“Anthems for a Seventeen Year-Old Girl” (Katy Perry? Lady Gaga? Even Coldplay?)