Maybe it’s time for the idea of a “commons” to get a new boost. Whatever the reason, BBC’s 16,000 sound effects are available to download – but with strings attached.

The BBC Sound Effects site offering has gotten plenty of online sharing. This is a sound effects library culled from the archives of the BBC and its Radiophonic Workshop, a selection of sounds dug up from broadcast sound work. There’s both synthetic sound design and field recording work – sometimes not really identified as such. I know this, because I used what I believe is the edition of this that was once released on a big series of CDs.

If you just want to listen to some interesting sounds, you can stream or download WAV files of sounds ranging from “‘Pystyll Rhadn’ falls, North Wales, with birdsong” to lorries, and, this being England, lots of exotic sounds from the far reaches of the former British Empire and a bunch of business to do with ships. (There’s a reason English is dotted with obscure boat-related idioms like saying someone is “two sheets to the wind” when they’re drunk.)

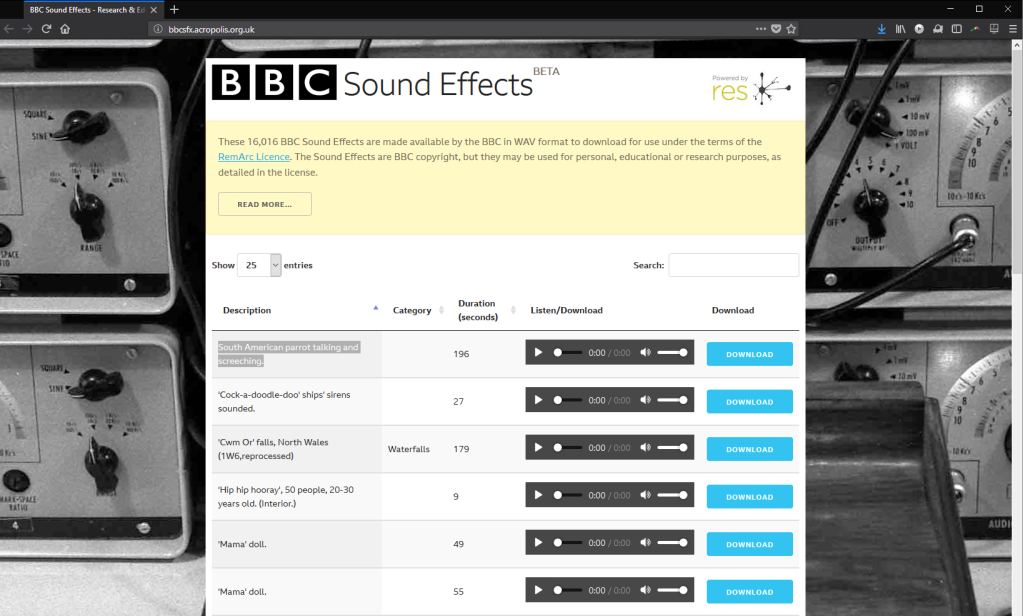

And it’s good fun. Right now the sound of a parrot is trending:

http://bbcsfx.acropolis.org.uk/

The catch is, you’re probably thinking of downloading those files and making a Deep House track with the parrot. But you can’t – not legally. If you want, you can wade through the murky terms, which seem to be written for schoolchildren in terms of language level, but oddly evasive about what it is you’re actually allowed to do:

I can save you the trouble, though. There’s no explicit allowance for derivative works, which rules out even “non-commercial” sampling. That is, your parrot track is out, even if you plan to give it away. Non-commercial use itself suggests you need to have a site that not only has no ads (like this one does), but may even explicitly have some educational purpose. “Personal” use implies you can sample the sounds, so long as no one else hears your remix, which rather defeats the point. So you almost certainly can’t sample the parrot and even upload the result to SoundCloud.

Correction: Jake Berger from the BBC writes to clarify that derivative works are allowed if they comply with the non-commercial requirement (and attribution). Non-commercial definitions have been challenging to define in the past, however; I’ve written him for additional clarification and will share it here.

The easy way to look at this is, you can build an educational app around these sounds or listen to them on your own, but you can’t really use them the way you’d tend to use royalty-free sound samples.

For that, you need to buy a licensed product. Sound Ideas has the full library for around four hundred bucks. And then you can use, they advertise:

1936 Raleigh Sports Bike

Euston Railway Station

St. Paul’s Cathedral

1986 Silver Sprite Rolls Royce

Audience Reactions at the Royal Albert Hall

County Cricket Match

Big Ben

Markets in Morocco, Algeria, Niger, Zaire, Ethiopia, Kenya…

I’m sure the CDs themselves also had a lot of license restrictions attached, though owning a physical object might make you feel as though you had purchased rights for use.

British taxpayer license fees fund this sort of work, just as taxpayer money funds media in many countries of the world. That raises the question of what a government funded archive should be, and how it should be made available.

For background, this project came out of a now-ended four-year project to make UK archives publicly available:

https://bbcarchdev.github.io/res/

I’m not arguing the BBC have made the wrong choice. But it’s clear that there are two divergent views on public archives and content in the public sphere. One looks like this: the government retains copyright, and you can’t really use them beyond “research” purposes. The other is more permissive. For instance, the US space program actually does allow commercial use of a lot of its materials, provided an endorsement is implied. So even while releasing content into the public domain, the US government is able to avoid implications of endorsement or people posing as their space agency, which the BBC agreement above does, while allowing people to get creative with their materials.

And that ability to be creative is precisely what’s lacking in the BBC offering. Restricting content to “research” and “noncommercial” uses sounds like a lofty goal, but it often rules out the activities of artists – the very impulses that generated all those BBC sound effects in the first place. The reason is, unless you explicitly allow derivative and (often) even commercial use, it’s too easy for those creative uses to technical qualify as a violation.

It seems like this idea of commons could use a fresh boost, around the world. (The British taxpayer-funded sounds should have been an easy one; it gets much harder as you go to other parts of the world.)

The US government’s notions of public access content date back to the 1960s. But there are signs governments can begin fresh, digital-friendly initiatives. For one example, look to the European Space Agency, who last year managed an open access programs across a variety of different governments and private contractors (no small task):

Anyway, for now, it is still fun listening to that parrot.

http://bbcsfx.acropolis.org.uk/

By the way, speaking of Creative Commons: the feature image for this story comes from Paul Hudson, taken at Rough Trade East (of a tape machine from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop collection), under the attribution-only CC-BY license. It was released on Flickr, from a time when this sort of license metadata was deemed important.

Clarifications – what you can and can’t do

Correction: I originally wrote that derivative works weren’t allowed, they in fact are. This was based on misreading the license; I regret the error. You do still need to keep that use non-commercial however.

I spoke to Jake Berger, Executive Product Manager, BBC Archive Development, who reached out to us with that correction/clarification. The most important requirement here is that free use of the online archive not make you any money. Now, not making money while making music is (ahem) fairly easy, but you should note that definition can include things like having your music on a site that contains ads – but if you want to, say, charge a couple bucks for your track, see below.

Jake gave some examples of uses that would be allowed:

Student film competitions

A ‘Sound Garden’ at a hospice

Research in to sound therapy for people with PTSD

School music lessons – using SFX in composition lessons

Use in history lessons (playing recording of WW2 air raids in lessons about the blitz)

Use in free-to-access artistic installations

Use in musical compositions that are not commercialised

Using sounds to trigger memories in people with dementia

Basically, the logic here is that this public project also needs to generate revenue from private use. The BBC also has commercial activities that sell the full subset of sounds here, plus about another 15,000, says Berger.

You can also buy all 30,000 sound effects royalty free for around US$5000, but you can also get individual files for around five bucks.

So there’s your answer. Audition sounds via the free site. Use them to finish your semester project in sound design for that installation for which no one gets paid. Then sample the parrot in a deep house track, pay the $5, and make untold cash when it tops Beatport and you get booked to Ibiza.

https://download.prosoundeffects.com/#!explorer?custom_17%5B%5D=BBC%20Complete

Actually, wait, I am totally going to make a parrot deep house track now. If you do, get in touch, we can be on a compilation. Heck, if four of you are up to it, I can get the fee down to US$1 each.

Thanks, Jake!