If you’re following music acts, odds are you’re already seeing Spotify-generated stats and graphs from artists. There’s a backlash to the practice – and with good reason.

First, before I sound immediately anti-Spotify or anti-streaming, this isn’t necessarily about that. There are reasons to distribute music to streaming services, and ways of leveraging that distribution to financial benefit (albeit largely indirect).

Putting aside the streaming business model itself for a moment, though, let’s consider what artists are doing here. Spotify sent an email last week to all artists registered for the Spotify for Artists program, with a link to “2019 Wrapped for Artists.” You need to be an artist with music on Spotify, but that’s it – the company even says you only needed three (!) listeners prior to the end of October to qualify for the “Wrapped” report. (Mine for some reason isn’t available, so I’m guessing there’s some lag from demand.) The service coincides with a “Wrapped” report for listeners/fans, which shows which tracks they streamed most. (Richard Lawler wrote this up for Engadget.)

The artist email email concludes with the instruction to “share your highlights with your fans on social.”

Here’s where things get weird – a whole bunch of artists just read that, and did as instructed. (Top tip to those artists: if you get a deal from a Nigerian prince or someone promising to, uh, improve some aspect of your anatomy, I suggest applying some caution before you act. Cough.)

Ironically, I heard about the backlash to the wrapped artists before I started seeing reports. Here’s one good example:

To that thread alone, there were some compelling responses:

But then once they began appearing, the flood of reports posted to Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter has become unnervingly commonplace. With apologies to those of you who did share this for some reason already, here’s why I think critics are justified in sounding an alarm.

What stats are included:

- Total fan hours streamed

- Highest number of fan streams per hour

- Increases in followers, total listeners, new listeners, streams, and playlist adds

- Number of hours fans streamed between 1am – 6am

- Number of countries where fans are based

- Country that grew by the highest percent of listeners

- Number of fans that had the artist as their #1 artist

Source: Hypebot.

Note that of these, only one element – growth by country – is really useful for gathering data about how you’d want to expand your fan base or, for instance, where to tour. (SoundCloud has offered similar data, too, for years, in greater detail.) The rest is all about feeding Spotify’s goals, which is to say, increasing the amount of streaming engagement on Spotify. Even without considering the pittance of income that generates for artists, it isn’t about you. It’s about building Spotify’s business, Spotify’s growth, Spotify’s core data – improving engagement for them, on a platform they own and control.

But why should I make that argument, when Spotify makes that argument for me?

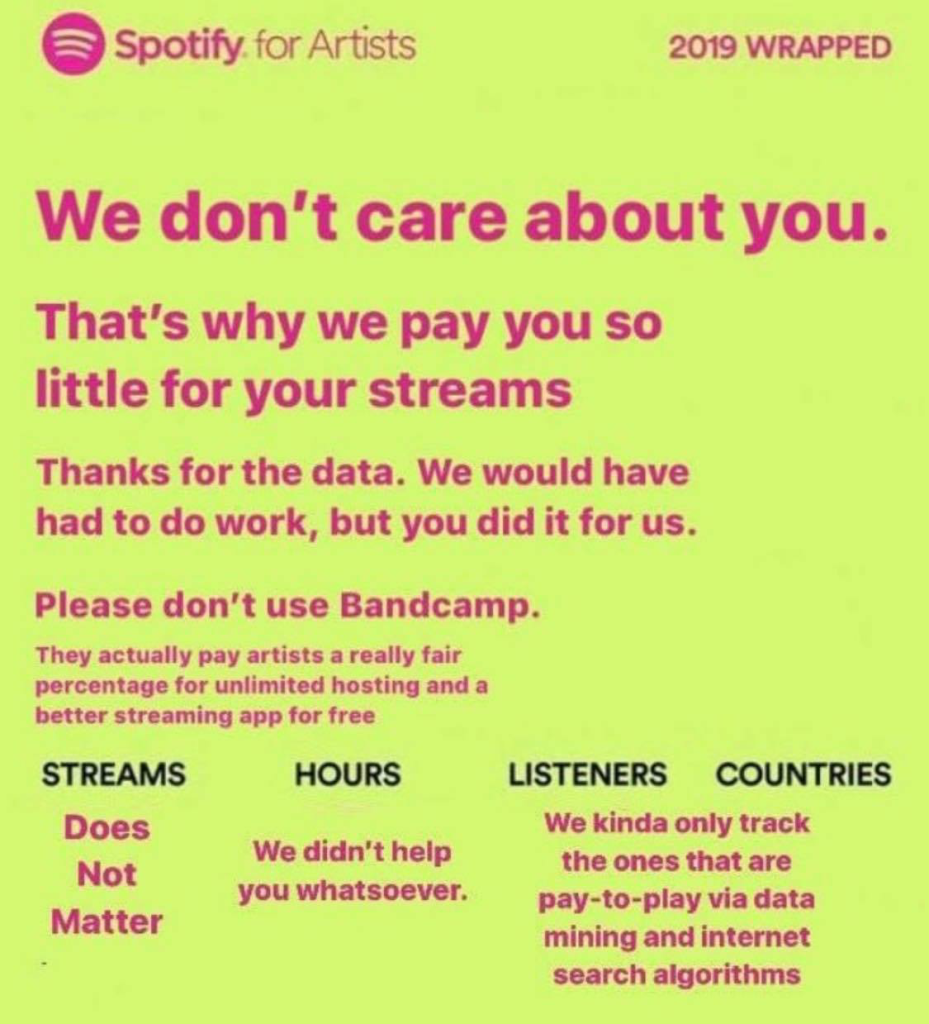

In a statement, the company says they’re “dedicated to growing careers and sustaining momentum.” The key is how they define “momentum,” which is driving up playback stats and getting music “on repeat.” But unlike a platform like Bandcamp, that doesn’t include ownership of the music or any way to offer merchandise (which generates more revenue) or ownership of listener statistics, which might assist you in planning a tour or connecting with fans directly. And even if more Spotify streaming helps you get gigs by increasing your fan base, or helping people discover your music through playlists, that still doesn’t explain why you need to share those stats with fans.

https://artists.spotify.com/blog/artist-wrapped-2019

Growth, growth, growth. As Spotify puts it, “for 2019 we’re focused on growth and velocity: all the ways your career grew, your music exploded, and your fans had you on repeat.”

What is that growth for, exactly? Well, it drives Spotify’s membership, and crucially it allows them to collect data they can offer back to advertisers.

It’s sick and twisted. By pushing you to focus on streaming stats, and then to share those same stats with your own fans, Spotify is driving home the idea that musical success is not how well you’re making out financially or how deeply fans care about your music or how it’s doing critically or your individual artistic satisfaction or literally any metric other than how much valuable user infomatics it is generating for a third-party corporation.

If they were just doing this to you, that would be one thing. But then they’re asking you to telegraph the very same message to your own fans.

Having made you do all of the work of making the music and promoting the music and then figuring out how the heck to get people to find it on their closed-box platform, they now want you to do additional work of pushing their corporate propaganda to everyone you know. (Heck, even in a pyramid scheme, you at least sell some inventory. Here you give it away for free and still lose out to the folks at the top.)

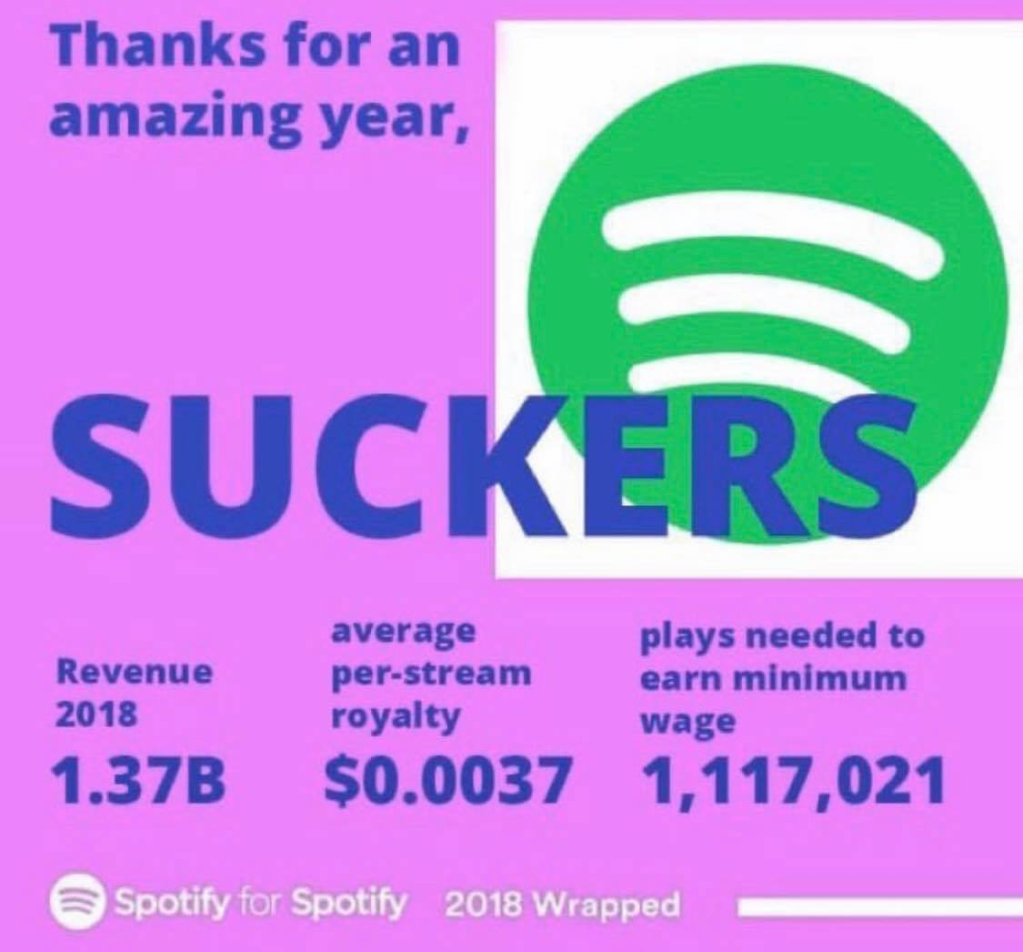

Here’s the only answer you really need to offer:

“But wait, isn’t all of this valuable to me? Shouldn’t I be grateful to what this service is offering me in promoting my music?” Okay, while I try to sort out the weird BDSM relationship we all now have with this corporation, here’s more evidence they really don’t have your interests at heart. In the same statement unveiling the service, they proudly announce:

“[We have a] steady stream of new features and resources, dedicated to growing careers and sustaining momentum; tools like Canvas, which lets artists add looping visuals to their music, and Marquee, which gives artists and labels the ability to sponsor new music recommendations.”

Let’s just translate there. they’re now giving you the ability to produce visuals for their platform on top of the nearly-free music you’re providing, and then to give you the “ability” to pay them money to get your music out there.

Wheee! So I can celebrate with my fans how much I’m part of a faceless algorithmic streaming service for which I earn nothing, punish myself for not getting heard that much, then pay the service to try to get heard more! Oh, and like make animated loops for them. Fun!

Because that’s the other evil part of this: the more Spotify dominates music listening, the more their ability to charge artists and labels for the privilege of being heard rather than the other way around. It’s just the old-fashioned pay-for-play scheme. I don’t doubt that some artists are blowing up this way, in which case, great! But the rest of us should delete this idea and move on.

Oh and by the way – this system benefits big industry conglomerates who are put of why Spotify is able to grow so fast. Those industry giants will often lock you into contracts where you pay them to pay for playlists and other exposure to get into the most-streamed music on the service.

This is not to say that streaming itself is evil. Streaming on its surface is just a different way of delivering digital files. And if your music is distributed at all on Spotify – either via your own self-released music, via distributor, or via another label – it makes sense to register for Spotify for Artists. By registering, you can track stats and control how your profile is seen, as well as find some other resources. Read the FAQ on that. It’s just dubious that you should join in sharing statistics, even though normally thanking fans is good practice.

There is at least some hope that we could see a better business model for it. On Bandcamp, streaming is already tied to ownership – and at least for my part, I love streaming that music from the Bandcamp app even as I was happy to pay for downloads (or sometimes cassettes or vinyl or merch) on the site. Beatport’s streaming service for DJs is new, and the jury is still out on whether it’s good or bad for independent artists, but at least it attempts to a) set higher subscription fees for listeners, b) get a bigger chunk of money back to producers and labels, and c) drive casual DJs to spending more on serious consumption. I’m still researching whether the service delivers on the company’s claims, but even as far as the claims, this is a far cry from Spotify, who seem to openly celebrate the fact that they’re screwing you over for stats and revenue for someone else.

And again, maybe you’re happy with how Spotify is working for you. In that case, though, I’d still ask if you want to be sharing stats, assuming you’re in this music business to be in the business of actually making music.

In this rapidly shifting landscape, we need to keep a critical view of these tools, and constantly adapt to make them work for us, not turn into corporate shills for their agenda. That may well include actively engaging Spotify, but it almost certainly doesn’t include “sharing” corporate media with your fans.

I’ll tell you what makes me happy, though. I’m deeply satisfied that artists are striking back, and often in witty and hilarious ways.

So, Spotify, if you expect to “see us in the 20s” as you so proudly proclaim through a deep fog of corporate positivity – you may be seeing more of us in a way you didn’t expect.

Artists generally having fun:

Many artists are sharing their stats, and then sharing how little they earned (these guys got twelve bucks):

Music Without Borders editor Anil Prasad shared this detailed takedown, which also deals with Spotify’s corporate backers:

Here’s a thought: share music instead.

Oh and … no, listeners aren’t necessarily happy either:

Spotify Wrapped: users alarmed by their own listening habits

Maybe in the next decade, we’ll decide that all these stats aren’t such a good thing.

More memes and text

Here is Anil’s full text, so it isn’t locked away on Facebook (reused by permission of the author):

The streaming truth no-one wants to hear or deal with: We’re all being hit by tons of “Spotify Wrapped” and “Spotify for Artists” propaganda, currently. Artists are engaged in a creepily-competitive, private-parts-waving campaign to show the magical number of streams and listeners they have, notably excluding the complete lack of survivable income any of it generates.

Once again, I’m going to lay out why things are the way they are in the streaming universe. Here is precisely why musicians don’t get paid anything meaningful. It’s a lot to take in and involves sitting there and pondering the monumental, corrupt expanse of it all. So, here it is. Choose to understand or continue living in blind ignorance, selfishly feasting on “free” without worrying about the macro, unsustainable consequences. It’s up to you.

The actuality of what articles on “How streaming saved the music business” written by the ill informed cover is six major businesses: Spotify, Apple, Google, Warner Music, Sony Music, and Universal Music. The first three are technology companies. The latter three are in fact, not music companies, but pieces of mega-media multi-billion-dollar conglomerates. Warner Music is part of Warner Media. Sony Music is part of the larger Sony umbrella. Universal Music is owned by Vivendi. All six companies are publicly traded on the stock market.

The latter point is the most critical. Before delving into that, remember that Warner, Sony and Universal are all investors in Spotify. None of these companies are interested in the vagaries of music, musicians and royalties remotely as much as they are interested in stock performance, valuation and market capitalization. It is why there is such callous disregard for the musicians and indie labels so drastically affected by their actions.

All these companies care about are aggregate numbers: the hundreds of thousands of new streaming accounts, paid or unpaid (it almost doesn’t matter) added and the hundreds of millions of streams that occurred across the current fiscal quarter.

These numbers are then revealed to the companies’ investor communities on quarterly earnings calls. These “performance metrics” then rapidly translate into investor interest and if the numbers are good, send the stock price higher, increasing market capitalization value.

Specifically, this is why all that matters is streaming numbers. Physical sales are irrelevant, as are download sales. It is also why artists are pounded on to promote and boost their streaming numbers to the exclusion of everything else. The corporations say this is in the artist’s’ interests. No, it’s exclusively about how to boost their stock price.

Now, in the case of Warner, Sony and Universal, they win in multiple ways. As investors in Spotify, they benefit from Spotify’s stock value increasing. And when Spotify’s stock value increases, guess what? It has a positive effect on their own stock. Boom. There’s the rub. Those three also benefit from the same awful contracts that paid out next to nothing in the physical realm. They keep the lion’s share of all streaming royalties too, leaving musicians with next to nothing, comparatively. Yes, it’s a wonderful triple play for them. You may want to re-read the last paragraph again. It is literally the crux of “How streaming saved the music industry.”

If any article you read on streaming and the music industry doesn’t mention any of the above, the writer almost certainly has no idea what they’re actually talking about. Sadly, that’s pretty much every writer. These concepts are way too heavy for the average, superficial music journalist to contemplate and the streaming companies love that fact and use it to their advantage.

Do what you will with this information. If you actually made it this far, congratulations. You’ve swallowed the red pill and get to contemplate the bitter, uncomfortable reality it delivers.

Anil Prasad is editor of Music Without Borders.

Again, I would actually go further than he does, which is to say conglomerates like Universal now also offering distribution and marketing services. They’re effectively double-dealing: in a world where a growing number of people want to be artists, they can charge for the privilege of promoting music, then collect those same charges (if they control the playlists), then negotiate their own fees to make money again from the music being streamed. This isn’t so different from the kind of model that fueled the industry before, but there you see where this “we saved the industry” idea came from. It wasn’t your industry they were saving.

And there’s a darker side, too – they could starve out the very people wanting to make music in the first place, partly by controlling what gets streamed. And that, in turn, is why you should avoid the stats.

This obviously deserves more investigation, and if you haven’t read a lot about it, that could be because there’s some pretty strong disincentive to people blabbing about it.

On the other hand, it looks good if you’re a Universal investor, I guess. Give away your music, make somewhere else, and buy stock? Dunno.

The problem there – the whole thing could burn out cash and implode. So there’s that, even for the investors. Worse, the rest of music has to climb out of the crater that’s left, now with everyone’s expectation having shifted to music being “free” and people forgetting how to collect music on their own without algorithmic help. Fantastic.

Some other memes that have been circulating, though I couldn’t locate a source (if someone wants to claim them):