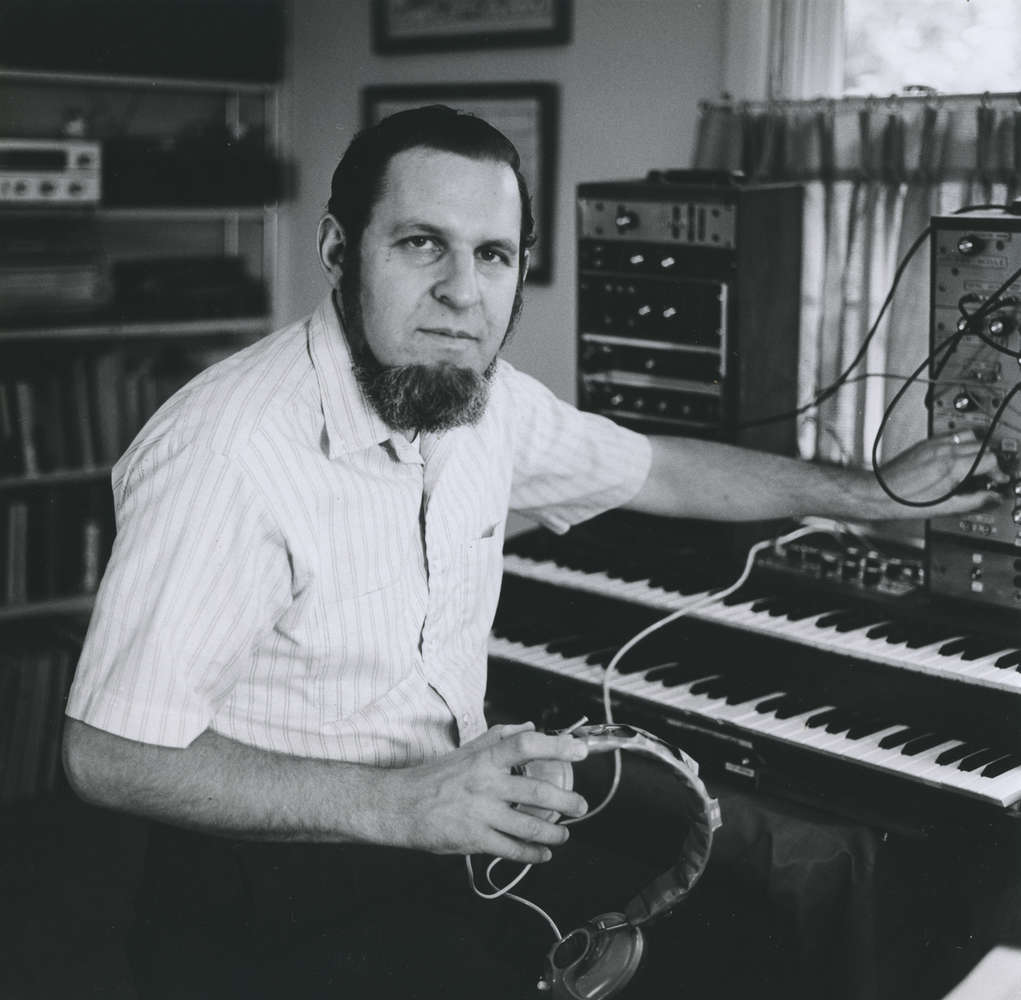

Herb Deutsch, one of the leading figures in the early development of the synthesizer and a lifelong educator, died on Friday.

News reaches us this weekend, and Moog Music has made an official announcement.

Today we celebrate the life of our friend Professor Herb Deutsch.

As a colleague, Herb helped Bob discover his passion for being a toolmaker. Together they developed a model for how engineers and artists may work together to achieve their creative dreams. The belief that an instrument’s designer must understand the artist’s mind and creative needs remains the core of all that we do at Moog to this day.

As a composer, Herb helped show the world how song is one of the greatest languages for storytelling. He believed in the power of music and recognized its role as a catalyst for change.

As an educator, Herb touched thousands of lives over his 50+ years of teaching. He inspired many to form lifelong relationships with music and composition. His students will remember him as a man who dedicated his life to making the world a more wonderful place through sound.

As a friend, Herb gave us the gift of a gentle smile and never let us forget the importance of kindness for our fellow humans.

Herb’s legacy and place in the history of music will never be forgotten. And here at Moog, his laughter will be missed and cherished.

We are endlessly grateful for your friendship, collaboration, guidance, and creative spirit, Herb. Our love is with you and your family.

I wrote a round-up of Herb’s many contributions to the synth world at large earlier this year. Honestly, my hope has been to express more when folks are still with us – young and old, since we never know how long they or we will be around. I hope we hold each other to that.

That’s not to take away the importance of honoring and celebrating people as they pass, though. Our hearts go out to the friends, family, students, and colleagues in education and at Moog.

One seminal historical reference appears to be offline currently, but you can read it in archive – 2003 and 2004 interviews with the Internet Archive:

http://web.archive.org/web/20210507102031/http://www.moogarchives.com/ivherb01.htm

After first meeting for hours in Rochester – the two had bonded over Theremin kits – Herb and Bob two chatted about the future of musical instruments over Italian food in Greenwich Village in 1964. There, they imagined a world-changing product that would become the Moog modular – the goal being, in Herb’s words, a “small and affordable music synthesizer.” Herb is also credited with championing the keyboard interface that helped render the synth accessible to musicians accustomed to keys.

Herb tells the story of making that argument. It might bother modern advocates of alternative interfaces and more inclusive interfaces for musicians around the world. But then again, for a company in 1960s upstate New York, it almost certainly was an essential business decision. (You could argue, even, that making that business decision has widened synth making to the point that now we can make more adventurous choices.)

From the above interview:

At the time I was actually still thinking primarily as a composer and at first we were probably more interested in the potential expansion of the musical aural universe than we were of its effect upon the broader musical community. In fact when Bob questioned me on whether the instrument should have a regular keyboard (Vladimir Ussachevsky had suggested to him that it should not) I told Bob “I think a keyboard is a good idea, after all, having a piano did not stop Schoenberg from developing twelve-tone music and putting a keyboard on the synthesizer would certainly make it a more sale-able product!!”

As a composer, Herb also was a stand-out, writing the first recognized piece for the modular instrument as well as performing at the legendary Jazz in the Garden concert at New York’s Museum of Modern Art:

That was a most unusual event. Bob designed and assembled four modular systems. One was a rather typical simple system used primarily for bass sounds and voices, a second was much more complex, and assembled to allow a soloist to access a wide variety of voices with fast selection by both patching and flipping switches…that was the primary synthersizer. A third and very interesting unit was one designed to provide many different percussion, cymbal and drum sounds playable, of course, from a keyboard. The fourth was actually a hybrid of Moog modules with a polyphonic keyboard which allowed the pianist of the group (Hank Jones was the wonderful player in my quartet) to play solos as well as “comp” behind other soloists.

When putting together my quartet, I first called Herbie Hancock asking him to play the polyphonic synth at the MOMA concert. I don’t remember his exact words, but he felt that at the time, synthesizers and electronic music were things he didn’t know enough about (pretty amazing considering where he went within 4 years of that concert!!). It was Herbie who suggested that Hank Jones might be interested, and it was really an honor to get to know Hank. He (one of the famous “Jones Boys”) then went on to appear as a soloist with my Hofstra Jazz Ensemble a couple of years later.

Jazz in the Garden was amazing for many reasons: 1) the instruments were not completed until two days prior to the concert, so rehearsals were VERY limited. 2) The event was incredibly crowded and quite thrilling (with the air filled with the smoke of hundreds of joints). 3) The close of the concert, which is very well-documented, was dramatic, because someone stepped on a power cord, pulling the entire ensemble into silence – – – which the excited audience considered part of the show and screamed their approval.

I hope you all enjoy the adventures of your own musical and technological inventions. RIP, Herb.