On tablets, on displays, multi-touch control these days is calibrated largely as a software interface – more Starship Enterprise panel than violin. As such, it works well for production tools and exploring compositional ideas. But it falls far short of being an instrument: even on the much-hyped iPad, touch timing and sensitivity is too imprecise, and the absence of tactile feedback and real, kinetic resistance makes you feel like an operator rather than a musician.

Several projects in experimental instrument research seek to change that. But of all of them, the one that has generated the most enthusiasm is Randy Jones’ Soundplane, co-developed with hardware designer Brian Willoughby. CDM shares a conversation today with Randy about his brilliant Aalto synth, and I’m working on a review soon. But wonderful as Aalto is, many of us are still eager to hear more of the Soundplane controller. I chose to wax poetic and optimistic back in December of 2008:

Intimate Control: Multi-Touch, New Models, and What 2009 is Really About

I shouldn’t have put a year on my predictions, though – good things take time. (If I could clearly recall what happened in 2009, maybe my general prediction was correct. The past tends to blur together for me into a continuum in the manner of the modern technologist, a vague assemblage of stuff that happened in the 60s with things that are actually still in the future.)

The good news: Randy continues working on the Soundplane, and Aalto will help.

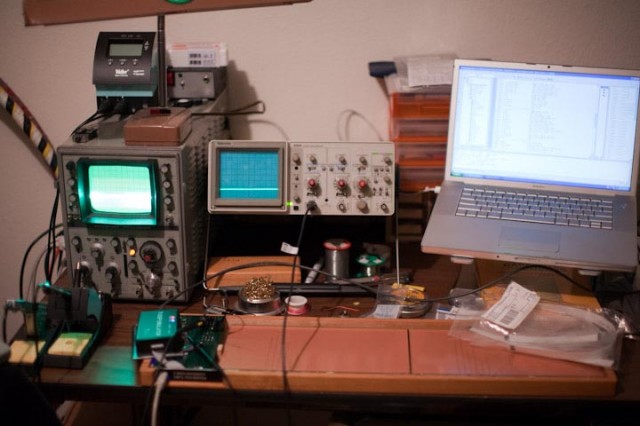

Continuing our interview, here are the thoughts most relevant to Soundplane — and a glimpse of what it’s looking like as he works on it in the lab.

First, Randy explains his ideas about running a small business, continuing what he had to say in our Aalto story. The basic idea: Aalto’s software will bootstrap Soundplane’s hardware.

I think the whole idea of venture capital is sort of a poisonous one. It’s a little like bands wanting to get signed right away. The first thing you want to focus on is giving up your autonomy, really?

Instead, why not scrape together whatever you can from friends or family and just make something that you can sell right away, however small. I didn’t have enough saved to finish the Soundplane project so halfway through I switched to putting out Aalto as a plan B for paying the rent. Now it’s out and it’s a product I’m proud of that I think reflects where we’re coming from, and it’s going to fund Soundplane development, and it’s letting tons of people know we exist. Just get a foot in the door, do something useful.

He also shares his feelings about patents:

Some people won’t like to hear this, but I applied for a patent on the sensor used in the Soundplane. I know, the patent system is totally broken, and often, if not usually, used in stupid ways. But if there’s one thing I think it is actually good for, it’s to protect small companies like ours that innovate against a bigger entity simply stealing their R&D. This is why it was designed, right? I don’t know if our patent will save the day if such a thing ever happens, but if it does I’d much rather have one than not. It’s a pain to write one but it’s not impossible, you just need a lot of patience. “Patent it Yourself“, Nolo Press, is a good reference.

The patent question raises some additional questions for me – in fact, I’d love to see open source hardware that’s also backed by patent protection, in the same way that the GPL license is made tenable largely through the existence of traditional copyright laws.

But I do tend to agree that in the case of a truly novel technology, which this is, patent protection may be necessary. The question for projects like this will be whether to operate as a conventional, patent-protected design, or whether some sort of open source model with a patent covenant and a copyleft license like GPL will make sense — both preventing exploitation and allowing free experimentation. If there are any IP lawyers lurking around out there, let us know (I have some contacts, too); and definitely let us know if that’s a conversation you’d like us to continue.

In the meantime, the important thing is that Soundplane lives, and using Aalto could help it come to fruition. We’ll absolutely keep you posted.

As proof, though, more shots from the lab:

Also, must-read article from shortly after Jones’ NIME presentation:

Why Soundplane?

The whole article is worth reading, but Jones argues that not only is it likely many people will try to do tactile multi-touch, but it may be necessary. For those of you not all that good at hardware design, you could be just as essential as well to there being any future for these curiosities. The designers need other designers. The hardware needs software creators – lots of them. The software creators need to try lots of ideas. And everybody needs players, composers … users.

It’s all-too-tempting to sit back on the Web and marvel at what everyone else is doing, to take their genius and novelty as an engraved invitation to give up on your own work. “It’s been done before.” “Someone else is already doing this.” It’s probably a topic for a dedicated article, but it’s simply the wrong reaction. “It’s been done before — maybe it’s worth doing. Or doing again. Or doing better. Or doing over and over again.” “Other people are doing this — that means I have someone else to do it with.”

Historically, revolutions aren’t solo pieces. They’re ensembles.

Updated: speaking of work being ensembles, while Randy’s name is most associated with the Soundplane project, credit is due to hardware designer Brian Willoughby, who did the hardware design for the instrument. As he wrote in comments on CDM in 2010, when we covered Roger Linn’s Linnstrument: “For my part, I’ve been deep into the process of designing the analog circuits, DSP hardware and firmware necessary for the product, so it’s nice to poke my head up for a moment and see interest on this site, as well as to hear about other engineers trying new things and inspiring ideas.”