Roger Linn is largely to blame for the fact that so many instruments have grids of pads on them. He was the first to use custom touch-sensitive drum pads on drum machines as we now know them, and the rectangular arrays of pads – first on the Linn9000, but particularly on Akai’s break-out hit, the 4×4 MPC60 – became an iconic and popular interface. But now, he has a design that might change the way you think about grids.

The problem is, input methods for digital instruments are still famously limited. Our computers themselves can produce astounding ranges of sound, but our physical connection to those vast realms is primitive. Pitch wheels and aftertouch are clumsy hacks for the absence of greater pitch control on keyboards. Grids have the same problem; some, like the influential monome, lack velocity entirely. Musicians have found ways of being virtuosic within those constraints, but that doesn’t eliminate the desire for something other than a big panel full of on/off buttons. Certain musical ideas require more of a gesture.

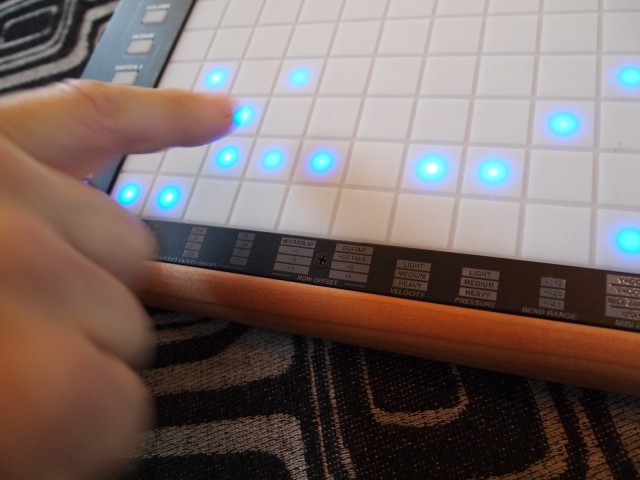

The Linnstrument is something Roger has been teasing for a while, but now, it’s nearing a finished form. I got a chance to try one out with Roger at Moogfest. Here’s the scoop on what the Linnstrument should offer.

25 x 8 layout. The first clever twist is the grid itself. Like devices such as Ableton’s Push, the grid can be mapped to pitch layouts. But by extending the horizontal to 25 spaces, you can easily reach the octave of a keyboard – even with the Linnstrument’s horizontal access mapped to chromatic steps. (That is, you get two octaves, plus one, which can also map to a 24-fret guitar.

For more portability, Roger is pondering a 16 x 8 version that more easily fits in a backpack for mobile musicians (and should be available at a lower price). That still retains the octave layout, which repeated eight times should give at least complete one-handed musical possibilities. With 25 x 8, you can play with two hands – either as a split or playing two different registers.

Expressive touch. The banner feature here is the ability to get not only velocity, but other expression out of your contact with the pads. You can slide your finger along a row of spaces for continuous control, as on something like the Haken Continuum. You can coax delicate pitch bends or timbral changes with nuances of your finger. And you can do all of this with a single gesture, as you would on another instrument, rather than disconnecting the expression with an additional controller (as a ribbon or pitch/mod wheel does).

By default, pitch is mapped on the x-axis; y-axis control is timbre. (This could be remapped if you like.) Crucially, though the sensing is independent for each axis and each pad. (You’ll want to use a host that has channel-per-note capability; Apple’s own Logic Pro X is one such example and what Roger used in the demo.)

Beneath the hood, Roger has built his own (patent-pending) technique for using force-sensing resistors for the job. Roger says he’s still working on tuning the defaults, but already the results feel terrific. My only gripe is that the silicon overlay, while it works well, is a bit sticky if your primary application is continuous pitch – at least compared to the fabric on the Haken Continuum. You don’t get the depth of pressure on the Continuum, either. But the Linnstrument is on balance far more practical: more portable and affordable by an enormous margin, and also more competent when trying to find discrete pitches, thanks to the added tactile feedback of the grid.

And the grid here shines: it’s like having eight Continuums stacked on top of one another (or, put another way, like folding a piano keyboard in on itself so it can take up less space).

Various pitch mappings. Pitch is a focus, too. In addition to chromatic mappings on the horizontal and fourths on the vertical, you can try options like guitar tunings – and the Linnstrument will dutifully send out the correct pitch values via MIDI.

Connectivity. MIDI over USB is an option, but so, too, is MIDI DIN for standalone operation without a computer. There are also jacks for pedal inputs. Roger has passed on including OSC (OpenSoundControl) – cue protests on that from OSC advocates.

Incredibly, even with all these superbright LEDs, the whole device can be run off USB bus power.

Quick access to performance presets. The default mode is already hugely useful, but there are loads of additional options, too. They’re being hashed out now in firmware – Roger said the panels pictured here are preliminary, and he’s already adjusted the feature set. But you get push-button access to various options as you play.

You can adjust lighting feedback, performance sensitivity (to pressure and velocity), and bend range, for instance. With RGB lights under each of the 200 pads, you can independently set color values both for primary and secondary states. There are octave controls – even with this many buttons – and customizable presets. You can also set up splits, especially useful as it divides the large Linnstrument into, say, 12 and 13 (or at any other split point you like — 8 and 17, etc.).

For more advanced control, there are options for strumming and trilling and sending specialized control messages. We didn’t get to delve into these too deeply, but it’s clear this is an instrument dedicated to providing a range of playing techniques.

Playing it as an instrument. Form factor is a big part of what makes the Linnstrument compelling to play. The metal frame keeps it steady as a desktop instrument – and the smaller version should fit snugly into live rigs – but there are also unique options once you add the strap. Roger modeled some of these, including holding the device against the chest and playing it in a posture similar to what you’d use with a washboard. I’m resistant to tacked-on wood as superficial in some cases, but here, it’s functional: the rounded wooden edges mean you can comfortably rest the instrument against your legs.

Looking to the future. I’m keen to see the Linnstrument completed and shipping. There may even be options for customization and hacking: Roger says the entire platform is Arduino-compatible. He hasn’t committed yet to opening up the firmware, but there’s a chance that could happen. I could imagine intrepid hackers augmenting the instrumental modes with pages for controlling Ableton Live, for instance, or building standalone step sequencers to exploit those MIDI ports. As with Push, you could toggle between instrumental and control modes.

But all in all, the Linnstrument could finally be a controller that rivals the ubiquitous MIDI keyboard for versatility. It won’t come cheap – those custom sensors aren’t inexpensive to manufacture. But it seems we can expect something in the more accessible MacBook Air price range, rather than the “small used car” price point of boutique devices like the Continuum.

Stay tuned here to see how this pans out. And Roger, I really do want one.

Rivals. The Linnstrument is, of course, one of many would-be solutions to expressive input, too numerous to mention. Of those, several commercial offerings stand out. The Haken Continuum I mention above as there were some particular points of reference to compare.

Another good comparison, as noted in comments, is the Eigenharp. Those, two, offer discrete control on each key. The differing actuation mechanisms yield different playing styles, however: the Eigenharp uses separate keys, whereas the force-sensing resistors on the Linnstrument make it practical to treat the entire surface of the grid continuously. The Eigenharp adds a breath pipe to that equation, which the Linnstrument lacks – but then, as seen below, you also have different playing positions when you hold the instrument.

In that sense, it’s best to think of these as distinct instruments with their own playing styles. The Linnstrument has two clear advantages over the Eigenharp, though: Linn’s device works as a standalone controller, and RGB LEDs provide more visual feedback.

In addition, there’s the Madrona Labs Soundplane by Randy Jones. While the Linnstrument is still just a prototype, a 30-unit run of Soundplanes is due later this week – the Model A for $1,895. And this device appeared specifically in the Amon Tobin video we saw recently. As with the Linnstrument, the underlying technology is force sensing, fundamentally. But the Soundplane uses capacitive force sensing rather than the Linnstrument’s Force Sensing Resistor (FSR) technology. Both systems are patented, and both systems sense force and X and Y position for three-dimensional input. This differentiates them from devices like the iPad, which uses capacitive touch but is incapable of measuring force.

The major claim of the Soundplane is accuracy and speed. Its communication is USB only – no MIDI. And it has a beautiful wooden body and surface, whereas the Linnstrument looks like a more conventional drum controller. The smaller Linnstrument, though, does afford some different playing styles and greater portability than the Model A. The big question to me is which is more expressive to play, and whether the Madrona piece offers substantially greater precision. For now, you can’t buy a Linnstrument, but when it’s available a shoot-out almost seems in order.

The Roli Seaboard is another recent option. It’s in the form factor of an upright instrument, piano style, and even shares piano-like key layout. But it can be played continuously, and pressing into the foam adds expression and pitch bend with tactile feedback. My only issue with it was, I felt like I was playing a mattress pad, and the stickiness of the surface made it less comfortable than the Continuum or Linnstrument. I had little desire to play it, but maybe others felt differently?

http://www.rogerlinndesign.com/preview-linnstrument.html [now partially outdated, but the principle is sound]

http://www.rogerlinndesign.com/

This hardware was far more refined, but here’s a playlist of performances (and one presentation) of the instrument from earlier:

Updated: This story now includes a couple of clarifications and corrections. Most notably, I was incorrect in saying Roger Linn didn’t invent the drum pad – as far as touch-sensitive pads as we now know them on drum machines, he did. That actually could be an entirely separate story. Also, I’ve clarified the description of some of the device’s functions.