Much can be said and felt with the human voice without words – and that’s where Robert AA Lowe comes in. With his solo drone/improvisational project Lichens, or lending his talents as a singer, synthesist, and instrumentalist to the likes of OM, Lowe has carved out a unique and powerful space as an artist with a deep focus on vocal exploration.

Before we move further, put this on while you read:

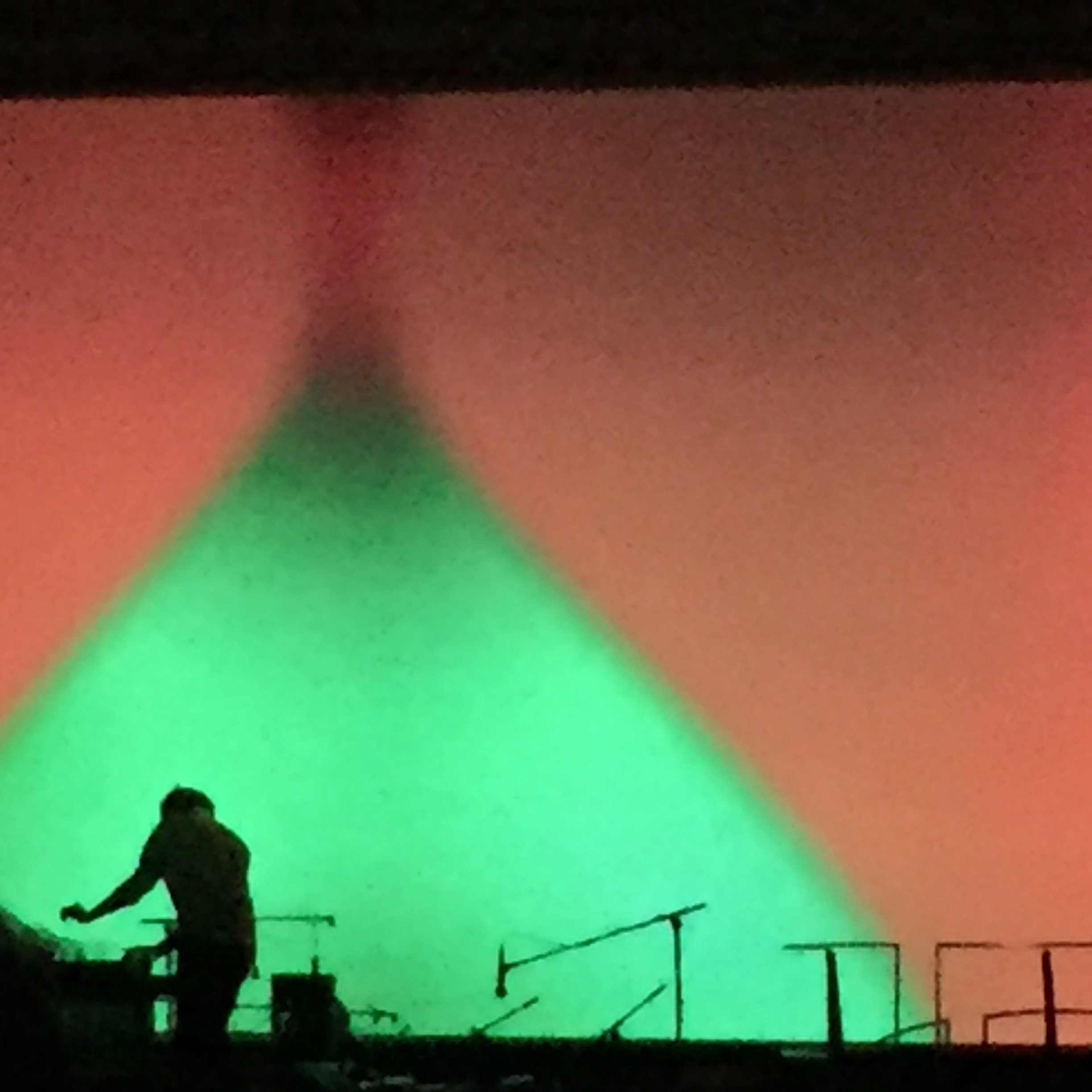

Lichens played an especially entrancing set during the opening concert of Ableton’s Loop event in Berlin – starting a fully unpatched modular rig complemented by subtle vocals, building to some incredible psychedelic drones and crescendos. Still recovering the next day, I had the chance to sit down with Robert for a discussion about hypnagogia, collaborative improvisation, and performance.

There seems to be this spiritual, almost holy element in your performance. How do you get yourself in the mindset for this performance? It seems like, in additional to the technical preparation, there’s a mental and spiritual preparation?

Well I guess, for me, a lot of where I’m coming from, and a lot to do with my process, has to do with circumstance and environment. Also, patching the synthesizer is something that, in a way, is very soothing for me. Because I do improvise, and every patch is done from the ground up. I was speaking with James Holden last night and he said, “I saw you open your case, and nothing was patched”, and I said “yeah, that’s how I work”.

This idea of predestination is uninteresting to me. So, in that moment, I will make that decision on where to put that first patch cable and go from there. It’s something that’s nice because I’ve been working with modular synthesizers for quite a few years now, and I’m very comfortable with them. And I’m very comfortable with the choices I make for modules. Even if I’m not fully understanding what they are, it’s the idea of the sense of discovery that comes along with patching them, moving them around, seeing what happens.

Even before that, when I started to engage this particular process as a solo artist, something that was very important to me was an idea of moments. This idea that you create a space, you create and environment, you create an atmosphere in this particular moment, and it’s something that’s happening in real time. Therefore, you will take that with you in a very specific way – as will the audience, in a performative situation. It’s something that’s interesting to me, is the fact that the human mind, and memory – these moments, or these memories, are approximations. They’re not exactly how they happened. Dealing with these ideas of perception of illusion, you get into this zone where you will revert back to that memory at a later date and remember it in a very specific way. For the individual it’s really nice, because it will hold something very singular for that particular person.

I think the human voice is an incredible instrument, and something that has not been utilized and really pushed.

Something that I thought was very important to me was this idea of trance, and losing the self, in a way. Even before I was utilizing modular synthesizers, I was focused on the human voice. The human voice is one of the most fascinating things to me, because they are unique – and they are. In my estimation, a little more so now than the time I started doing this, I’ve seen a lot more people utilize the human voice as an instrument.

I think the human voice is an incredible instrument, and something that has not been utilized and really pushed. You could look at artists like Meredith Monk or Diamanda Galas who have used the voice compositionally and instrumentally. My idea was to further this process, but, of course, cultivating my own technique. That’s also very important to me – this idea of not remaining inside of any sort of a box. One of my biggest problems – and when I give talks and lectures, I talk specifically about this – when, say, a young person goes to a conservatory or gets inside of academia, not every time, but I think more often than not, they’re taught that, “you are meant to utilize these tools in this specific way. You are meant to create in a very specific way” within these sort of rules that have been handed down.

Not only with music, but any sort of artist endeavor, these things can’t be qualified or quantified because they are creative. You can’t qualify art – it’s done, but it doesn’t make any sense to do so, because it’s an individualist expression. This individual expression is something that that person sees through, and they are compelled to do so in a specific way. If it is truly coming from a place of expression, then you couldn’t say that it was wrong. There is no rule. So, that’s a whole lot of my process.

You mention the struggle in teaching people how to make art. It reminds me of William S. Burroughs – as a professor, after a while, he wasn’t sure it was possible to teach creative writing. That he’d rather teach creative reading or listening. You talked about the moments – do you come with an intention of how the music or your performance will affect your audience? Do you ever talk to audience members about how your performance affected them? Are you ever surprised by what they take away from your music?

I think for the most part, something I’ve been concentrating on for the last year and a half, has been creating performance pieces to induce a hypnagogic state – a sort of waking dream. That’s something that I was always hinting at from the beginning, because of these ideas of trance. Before I was, say, utilizing modular synthesizers, where I had to be aware of what was happening in front of me, and aware of the instrument itself, I would do performance pieces where I would get completely lost. I would, myself, go into a trance, and just be gone. I wouldn’t be aware of what my body was doing, or how it was doing. These are all things that are important to the performative and experiential aspects of what is happening. I think that those things still exist – I find a different way in to trance.

Patching and moving the synthesizer is something that’s very zen for me. This idea of patience, and unfolding these things in a way that don’t lend themselves to maximalism. I think a lot of the time, when people get into modular synthesis, or synthesizers in general, it becomes very maximal. All of the sounds are happening and moving very quickly. It’s not necessarily the antithesis of the way that I work, but it’s definitely not in my realm. I wouldn’t say it’s outside of my wheelhouse, but it’s in the corner, at least.

Lichens – “Kirlian Auras”

The follow up from this, then – how do you approach recording? Do you ever feel like it’s stifling to have to record something that people can listen to in perpetuity? How would you approach that differently than you would a performance?

Honestly, in most ways, I deal with performance the same way I deal with recording. Recordings that I do are generally real-time. There are certain times that I decide to do multitrack recordings – but, always, these parts are improvised. I’m listening to these things as I’m doing them in real time. As I record them, and hit the playback, I’m listening to the layers as they build. But I’m not necessarily thinking about…I don’t necessarily have an end game. Once I reach a point that I say “okay, it’s finished”, then I’m done. It’s really that simple.

I also am of the mind that over-analyzing recordings, or thinking about things too much, is a detriment to the life of that particular recording. Generally, when you have an idea and you play through it or record it for the first time, it’s the freshest and most interesting iteration of that idea. The more that you try to recreate it, it lessens it, in a way.

I think that’s actually very different than, say, if you look at this idea of “ecstatic truth” that Werner Herzog will talk about, when he’s doing interviews for documentaries. He’ll interview someone, then interview them again and again, asking them the same questions, until he gets to the meat of the matter. I think it’s sort of the opposite of that when you’re looking at recordings. I feel like, generally, people drill themselves into a hole – and they’re unlikely to find this epiphany and say, “now I got it!” Sometimes it happens. But, at least for me, the earlier the idea, the freshest it is. This is my particular opinion, and this is dealing specifically with my process.

A SPELL TO WARD OFF THE DARKNESS (TRAILER) from Ben Russell on Vimeo.

You acted in and composed for the film, A Spell To Ward Off The Darkness. To what extent did the film and the ideas behind it inform your performance and your music?

The film itself was made collaboratively by Ben Russell and Ben Rivers. They asked me to collaborate with them in seeing it through. Their idea for the film was basically to pose the questions – “what is utopia?” and “how to humans live in the world?”

I think that the film poses these questions, but gives no resolution. There’s no answer, there’s no specific way through. It’s a creation in a triptych form – the film is following my character through these three landscapes. They could exist in a linear mode, they could exist simultaneously, like three different universes happening in real time. It’s basically just posing these questions, and not necessarily leaning towards one particular mode of thinking. Instead, it examines this idea of idea of utopia or commune – or failed utopia. This idea of solitude, and this idea of the sublime, or the transcendent.

As far as how the film was made…people ask me about acting in the film. It’s technically not a documentary – it’s a document, a construction in a way. They like to call it an “unfiction”, which I think is really nice. I looked at it very much as performing actions – it was acting, technically – but the way that we would talk about it would be as a person setting out to do certain actions, which would eventually become the body of the film.

How does your music change when you’re working on a film, as opposed to your own performances or recordings?

When I work on film, specifically, it’s a collaborative process no matter what. Therein lies this idea of compromise – you have to take a different viewpoint when you aren’t working alone. You have to be malleable in those situations. Definitely, I operate in a different way when I’m working in the realm of film or even in collaborative performance, to a certain degree.

One thing that most people don’t understand about improvisation is the fact that the most important thing is listening. I’ve come to this general overview that many people either overplay or get really crazy. It’s all about listening to your collaborator – understand what they’re doing, where they are. It’s a dialogue, not a racket – it can be a racket, but it has to be a dialogue first. You have to be able to bend and move and be malleable in these situations.

OM’s “Sinai”, featuring vocals from Robert

That’s an interesting point about listening. It seems like that’s also a valid point when you’re performing solo. I noticed that when you were playing, it seemed like each section evolved from the last one – it wasn’t a setlist-style format. How do you balance that in performance – do you take the time to listen to what you’ve made and then move on?

Absolutely. Also, with individual performance, in the realm of improvisation, you do have to listen to yourself. You have to listen to what you’re doing, and follow whatever path you’ve arrived at. Whether that, in your mind, was where it was meant to go, or where you had anticipated, or whether it had thrown you a curve ball and taken you down a different road. It’s all about following the framework as the bricks are being laid.

One more thing I wanted to talk about – the visuals in your set. There’s an unfolding psychedelic feel to them, not as much “in your face”. How does that relate to what you’re playing?

The visuals that I created specifically for the performances that I’ve been doing lately are done with analog video synthesis. The last few months, I’ve been working with a modular system that runs at video rate – creating these video pieces with colors and shapes morphing and changing. That’s also meant to become additive to the entire sonic process, and this state of hypnagogia; it’s meant to really push you into this state of dreaming, but awake.

David Abravanel is a digital marketer, futurist, and musician immersed in creative technology, currently based in San Francisco. dhla.me