There’s barely a performance medium that Robin Fox hasn’t touched, not a form with which he hasn’t moved us. From laser AV spectacles to exhibitions to work with contemporary dance (including the wonderful Chunky Move), this Australian artist is the kind of multi-faceted mind we adore. And so we sent Anahit Mantarlian for a marathon interview, so we can all geek out accordingly. -Ed.

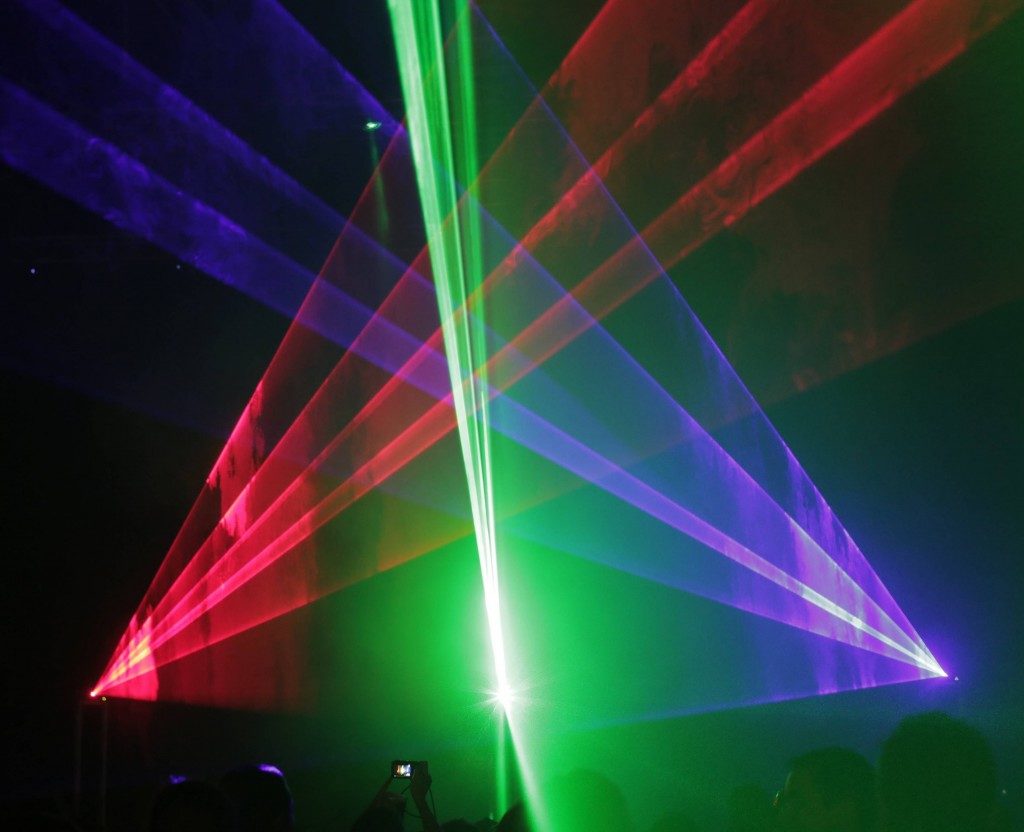

Audiovisual experimentalist Robin Fox has been busy. In 2016, the Australian composer and laser charmer toured Europe, presented his latest show RGB to Atonal Festival, performed at the inaugural MUTEK.JP Tokyo, and opened an organization (alongside Byron Scullin) meant to “open a wormhole into the history of electronic music” via rare synthesizers, MESS (Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio).

And at the Melbourne Fringe Festival, he has premiered an installation of macro proportions. “Sky Light” took over Melbourne’s night sky with a reverie of laser beams shining from the city’s highest towers (see pic at bottom), connecting dots to turn the capital into a huge audiovisual installation. To add to the thrill-inducing experience, Fox composed new music on the Buchla synthesizer especially conceived for the hyper-spatial occasion).

Over the summer during Atonal festival, we chatted casually with Robin about his future projects, key moments in his artistic process, and some beautiful influential books and concepts. The voice recorder did stay on, and that’s very fortunate, because now we’re sharing with you a piece that professes fascination for electronic music with every turn of phrase.

Robin Fox at Atonal.

Anahit: Did you come here straight from the airport?

Robin: Yeah, I played last night in Turin – the same show you saw with Atom, “Double Vision”, was last night – so I haven’t had much sleep.

I remember when I saw the show at CTM Festival 2015, I was very amused by the lyrics. “Mr Fox will make you see in RGB” was a lovely moment in the show. How did that rhyme come up?

Atom [Uwe Schmidt] has an amazing sense of humor – throughout his whole career, actually – the earlier techno works that he did always show that and, of course, Señor Coconut.

That’s the one where he’s doing the Kraftwerk covers.

Indeed. In his work, he always has those – as he calls them – moments of tension, where he likes to break what’s happening, and leave people with the sense that they have experienced something strange. In that piece, “Double Vision”, there were a couple of moments where we made the piece remotely, because he lives in Santiago, and I live in Melbourne, so it was a really long distance collaboration, happening a lot over the internet. Then we had a short period of time in Krakow before the premiere, where we finally were physically in the same place.

He wrote this beautiful pop song, “RGB”, for the middle of the piece. He also proposed a moment where everything stops, and there are just images of boxers, who don’t connect [their] punches, and it’s really slow and totally changes the whole pace. I remember when he suggested these things I thought he was kind of crazy, but I think he has a brilliant instinct for humor – and for the way it can work really beautifully without being cheap. He’s an amazing collaborator.

One of my favorite satirical commentaries of his, and a really obsessive track about pop culture, is “Stop Imperialist Pop” – it’s on this Atom line of humor.

That’s right. But I’m a total hypocrite, because I love that song and I also love Lady Gaga.

That makes two of us. But I don’t find it to be actually hateful towards pop.

I’m not really sure about that. (laughs)

Now back to Double Vision, there was also an animation, as far as I remember – adapted to the lyrics. How did that come about?

When we started working together, I was just working on a new solo project, which was an extension of my old laser work. I had been using a single green laser, and I started working with red – blue – green lasers, because I wanted to split the visual spectrum up like that.

So I was working with audiovisual materials, and he was working with video – there was some real connection in the way we were working. I was interested in this very direct, electrical, synesthetic relationship between the sound and the image. And he was, as well, particularly in the way he performs video and sound simultaneously live, so there is a physical connection that he forges between sound and image. When we came together to write that piece, we both brought a lot of information from the solo work that we do in our other projects. So I guess he wrote the song about RGB because it resonated with him — because of the way RGB is represented in all computer formats, in pixel form.

How did you decide on switching from green laser work to something involving the RGB color standard?

The work that I’ve done with green lasers is about sound and geometry, because there was no color. And I wanted to start to work with an expanded sense of color. That totally changed the way I work. I used to make sounds, and then visualize them with the green laser. Now, I almost draw pictures of electrical signal, and then listen to them. So I draw pictures of electricity with the lasers and then translate that into sound – it’s almost like hieroglyphics, or pictograms.

The solo show I’m doing here at Atonal is the solo show that I was working on when I started working with Atom. So it’s basically a red laser, a green, and a blue one, all controlled separately, and all of the sound that you hear is also the electrical signal that you see. So it’s what I like to call a mechanical synesthesia.

The concept of synesthesia is central to your work. Is it an intention you bear in mind before proceeding with production, like a vector? And I’ve read that this interest was initially related to your experience with an oscilloscope?

That’s right. The way I started looking at sound first was with an oscilloscope. So you plug in the left and right of the audio signal into the x- and y- axes, and then look at the sound.

Also, when I studied music at university I used to write compositions on paper – and I was quite frustrated with that, and so I started to examine why. I wrote a short thesis about graphic notation and drawing sound, even with notation – so even when I was interested in more traditional music and I was studying that form, what interested me about it was, how can you draw it? How can you express something in a non-linguistic, gestural form?

For me, something like music notation is a linguistic paradigm. It’s very much a language – and a lot of composers of the 20th century that I looked into then were interested in shifting traditional notation into a more graphic form. So I was into that even before I got a computer.

And you studied sound, as well.

Not always. I also studied Law and Literature first. But music was always around in my household. My mother was a composer as well, she wrote computer music in the 1980s, so she used to make music on the big mainframe computers, and my stepfather ran the Computer Music Department at La Trobe University, where I studied composition.

I was interested in sense perception, and also had this childhood experience of synesthesia through my mother, so it was always there – and then there was a chance encounter with the oscilloscope, so it was a combination of those things.

It was something that was already in my mind, but then it became real in that moment, and synesthesia became something that was no longer a romantic, mystical idea – it became a very tangible and real connection, between sound and vision – that could be experienced without having this cross model association as a neurological condition – you could experience it simply by putting sound into a oscilloscope and looking at it. That’s how it all began.

Somehow that’s why the brain recognizes it as something like an archetype that you knew forever.

I think archetype is a good description actually. I think that when I first experienced this mechanical synesthesia with an oscilloscope, there was something really powerful in that moment. It was just like a second and it all came together. It was like a jolt in my brain, and I knew there’s something in that connection, that I wanted to work with – which I did, for 15 years or so.

Did you come across this more by trial and error, or did you have like a neuro-insight about how the brain converts the same signal by sight and hearing?

It’s actually a combination of both things. I was always interested in sense perception, because I was interested in writing music. I was interested in the way you perceive information as a human being. There’s a great book James J. Gibson, written in the 60s, called “The Senses Considered as a Perceptual System”. That book was talking about sense perception as a complete ecology, as a whole way of being in the world, rather than that very western scientific method of isolating the hearing and the sight and the touch and separating them out and working out how they work independently of one another.

So it’s like the way we work on genetics at the moment, splitting it all up and figuring out exactly what each piece does. I’m sure in the end it’ll work out that it’s something to do with the whole thing that we missed by zooming in on the picture.

What type of synesthesia was your mother experiencing?

It was sound and color and number, so there were three things. Every sound had a number and a color. And every color had a number and a sound. So it goes in a loop. You know, synesthesia is romanticized in the arts as a kind of creative gift, but when I got interested in it, later in life, and I talked to my mother about it more seriously, it was almost more like a mild form of autism – in the sense that she said ‘you can’t switch it off.’ And sometimes you don’t want to make that association, so she described it actually more as a barrage. But it had helped in her career as a singer, for example, because she made perfect pitch associations so she could sing in perfect pitch whenever she wanted very easily.

Was she also making music?

Always.

Is it released somewhere? There’s a growing interest now in the work of female electronic musicians and composers.

Yes, it’s an interest I’ve had for a long time, via my mother as well. She passed away a few years now, but she did leave a legacy of a few pieces. She didn’t make a lot of pieces, but the ones that she left behind are quite beautiful. I have to find them all, and I should make them publicly available. I helped her put together a CD before she died of all the pieces that she wanted to have remembered. And there is one composition that’s for electronics and brass ensemble and a choir, because she used to sing and write beautiful choral music, this piece called “Maze Songs”, which I don’t think has ever been performed properly – maybe before I die I’ll make that happen.

Now I definitely want to hear that record – I’ll ask you for a track of your choice; it would be great if we could share it.

Sure. My favorite one is called “Death of an Insect”. It is based on a poem of the same name. It’s a short poem about a bird killing a beetle. It’s a brief poem, but it’s quite dark.

She turned her voice into a bird through electronic manipulation and it’s quite dramatic. Do you know Trevor Wishart? He wrote an amazing book called “On Sonic Art”. He had this practice in the 60s and 70s, of merging sound fields that shouldn’t sit together. An obvious example is crossfading together the sound of the city and the sound of a jungle, so you get this sense of an intermingled space.

How do you define your working relationship with technology? How did you come into electronic music?

When I was a child, all the newest things would arrive in the house, for testing [via his father’s university position]. So I had access to samplers when I was very young.

I would just get obsessed with things. There was a sampler that had a car crash sound, and I used to play that car crash sound for hours. There was also a cat sample, so there was a car crash and a cat meowing, so I remember alternating those sounds musically. Then, I was a drummer in my teens. I still love to drum – I think I was never as happy as while playing the drums. It’s like meditation: you lose sense of time even if you should be kicking time – which is also probably why I was never a good drummer. You lose sense of space; it’s really beautiful.

Now I work a lot with analog synthesizers. I think it’s a very similar meditation. The journey of making electronic music with these analog machines, where you start with nothing and gradually you build a sound, and you hear something that you’ve never heard before.

How do you work with it now? Do you, for example, work on redesigning every possible setting in Ableton and stuff like that, or what software do you use?

Believe it or not, I don’t use Ableton except every now and then – and I think it’s incredible. When I decided to work with computer music, I decided to learn one thing, and that was Max/MSP, and it’s more about building things from scratch. So I thought, if I learn this particular thing, I can do anything. Now, with Max for Live you can integrate this creativity into Ableton.

In terms of work, for me, it was always building things from scratch, in the end — finding the simplest possible way to do things. And the way that I work with the RGB show is so simple that it’s almost stupid. It’s just like taking the voltage that makes an image, plugging it into a mixer and then turning it up. And that creates this incredible connection between the sound and the image. But it’s also the most simple and direct way you can do that.

Would you describe synesthesia as a leitmotif you seek in your musical work?

It’s interesting because the synesthetic work that I do has been the most visible. So it’s what I do in public the most. But I’m constantly making music, so I also make a lot of music for contemporary dance, and I was actually adding it up recently. I think in the last five or six years I made ten contemporary dance soundtracks which I need to release.

I think sound is at the heart of what I love. I get frustrated sometimes about this misunderstanding that I am some kind of lighting designer. I’ve actually done some lighting designs and it’s not for me. Too much paperwork! For me, sound is at the basis of everything. I spend a lot of time in the studio, working on sound and music and generating sound, also a lot of field recordings – the last Editions Mego release was “A Small Prometheus” which was mainly the soundtrack to a dance work by Stephanie Lake with a focus on recordings of heat, and intensity.

How did you record heat?

There are a lot of ways to record heat. Some are obvious, and I like to start with an obvious premise because it’s that kernel that often leads to more interesting development. So I started with just the striking of a match and recordings of fire – which is not particularly radical, but it was quite beautiful to do it and to analyze those sounds and try to work with them compositionally.

The next experiment was to fill up a bath with water and put some bricks at the bottom to hold down a fire blanket, and then put hydrophones in the water, and shotgun microphones on top of the surface. Then I got some hot coals from a barbecue, and plunged the hot coals into the water. You get what you would expect [at first], which is a hiss, like when you put water over a hot pan. That’s an amazing attack anyway, but then as the hot rocks settled into the water – the recording is about 2 minutes long – suddenly it starts to sound like you’re at the beach, the sound of the sea and birds, even. It sounds really natural and organic, and strange. And from there it changes into these almost electronic tones, moving through the water. So that’s another way of recording heat or at least heat dissipating through another physical system.

Also, when I was on tour once, during that process, every hotel I stayed in I recorded the electric kettle. I did this because each one has a slightly different ramp time. They actually sound quite similar, but they take a different amount o time to come to the boil. It’s always this low, filtered white noise to begin with, and then it grows into a bubbling sound, then there’s the click – and it turns off. So each one has that form, but each takes a different path. So I recorded twenty of these kettles. The idea was that maybe I could transform them into some multi channel, massive kettle.

Like the hundred metronomes of Ligeti.

Exactly. And the rhythmic event would happen at the end, when they all click out in various timings. So those recordings formed the basis of a track from A Small Prometheus.

These days I’m working a lot with analog synthesizers. I just started an organization called MESS with my colleague Byron Scullin– that’s Melbourne Electronic Sound Studio. It’s a not for profit organization, a studio that’s set up for access, not for profit. Basically people become members, and gain access to an incredible collection of antique (and new) electronic musical instruments, things that individuals could never really afford, but we managed to find collectors and musicians willing to contribute their collections for public use.

We opened in April and it’s going really well. The online address is www.mess.foundation.

Ed.: Holy crap – dat collection. Swoon away!

Kaitlyn Aurelia Smith at MESS.

Sounds like an amazing library / museum.

I don’t like the word museum though, partly because there’s a problem with museums and electronic musical instruments particularly, because when an electronic musical instrument goes to a museum, the policy is that it never gets switched on.

That’s sad.

Yeah, it’s the death of it. Old synthesizers are like old cars, if you don’t start them, and play with them, they actually stop working. So the idea that they go into a museum and can’t be turned on just in case it breaks them makes no sense. What’s the point of looking at a synthesizer?

So MESS is definitely not a museum, in the sense that it is a collection of musical instruments that all function and work and are accessible to be played. They’re constantly being repaired; some are older than I am, and they need care! But it’s been a very rewarding experience to set that up. It’s taken a lot of the last couple of years of my life, actually.

Did you have a lot of artists in residency already?

We just had a short artist residency with Puce Mary. She came to the studio and made some really fantastic stuff. She came over just as I started this tour, so I only got to spend a day with her. We have other residencies planned; we’re definitely hosting people from all over the place. Chris Clark from WARP records is there quite regularly, because he lives some of his time in Melbourne. We also are lucky enough to have Keith Fullerton Whitman who lives in Melbourne now as well, so Melbourne is becoming like a place for great electronic sound making.

Last but not least, I wanted to ask about the evolution from the more apocalyptic music you were doing before, to the more technology-oriented, abstract or sensory. Is it a change of philosophy?

The one thing that nobody can avoid is getting old, and the difference between people is how they decide to do it. I am a strong believer in the fact that people change, as they move through life. So I definitely don’t have the same sonic energy to put out as I had when I was making those earlier records.

Was it more a rage impulse?

Not really, we (Anthony Pateras and I) used to have an incredibly good time making music, there was a real sense of joy. Even when we were making stuff that would be considered noise, maybe even bordering on harsh noise (laughs) we never really went there. To us, it was very ecstatic, in a way – it was a statement of life, not of the negation of life.

A lot of the stuff that I make now is different because that energy has shifted. I just finished a half-hour composition for a piece that I’m doing in Melbourne, where I have 16 lasers mounted on a skyscraper in the Melbourne CBD, and I shoot them into the city, like a constellation. I made a piece of music using a Buchla synthesizer, which you can download and listen to while you walk around the city as an active experience. That’s a meditative piece, and actually melancholic. That surprised me, because I wasn’t trying to make something melancholic, but with the Buchla you always start with an idea and end up somewhere completely different. You know, I’m also making some music now that might be considered quite popular, or tend towards that style as well – which I haven’t released yet.

Popular, in which way?

Music you can dance to, for example. If you come from where I came from, which is the avant-garde, noise community, sometimes putting a beat with something is like selling out, or doing something too easy. There is this idea that everything has to be difficult. I don’t believe that, I don’t believe that everything has to be complicated, anymore. And I think that’s one of the energies that I lost, the energy of radicalizing something for its own sake. And this is why I think it’s about youth actually, because I feel that when I was younger, that radical energy was just there, it was coming out, it wasn’t like a choice, or a thing we were trying to do, we were just doing that, and it made sense, and it felt right. If I was to try do that again now, I don’t think it would feel right, I think it would feel strange, and I think it would feel foreign to me now.

It’s like over years you get to different means of expressing that raw energy. I was listening to noise and black metal when I came across your work. And well, that is a very problematic music to enact in your everyday life, but I think what gets you most hooked is the ecstatic feeling to it.

Yes, that’s adrenaline. I realized something about noise when I read this quote that sound is the fastest sense. When you hear something, it’ is quicker than your vision – and the reason is that sound goes directly to your reptilian brain, so that’s why when you hear a loud noise you get that fright. And what happens to me when I listen to noise, or experience it and particularly when I used to perform it is you’re in a constant state of that adrenalized feeling. That’s a great feeling – and again, doesn’t have to be negative. Adrenaline is often seen as negative but it doesn’t have to be so, it’s quite exhilarating.