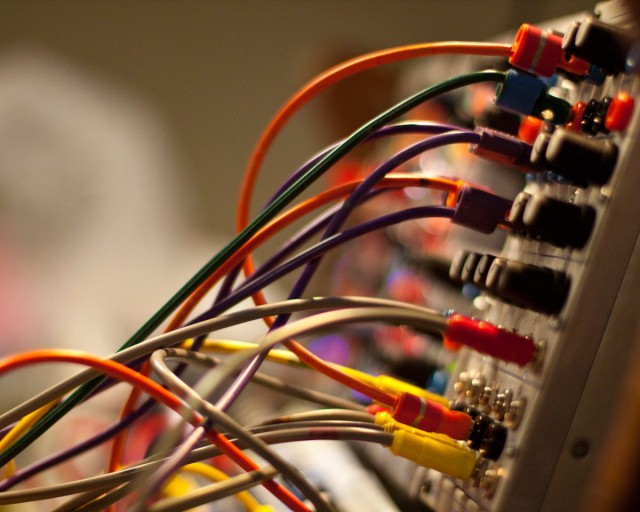

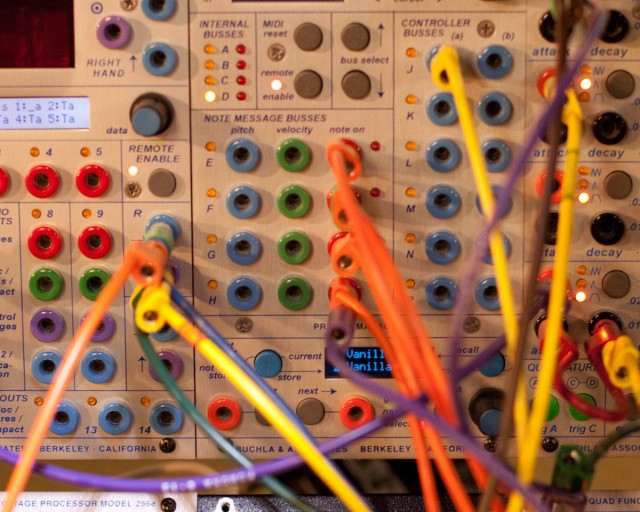

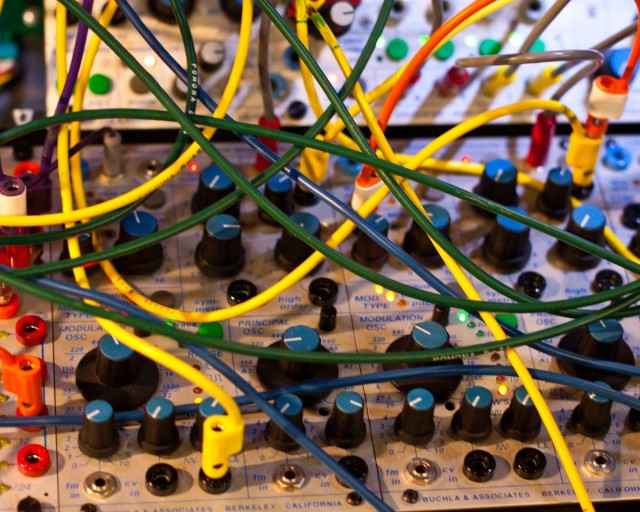

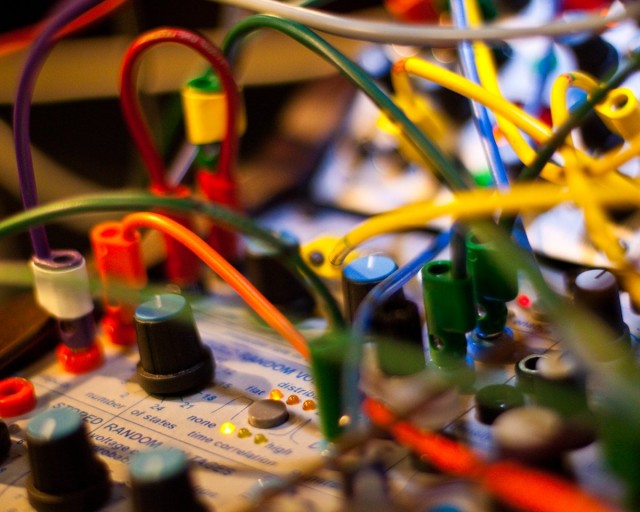

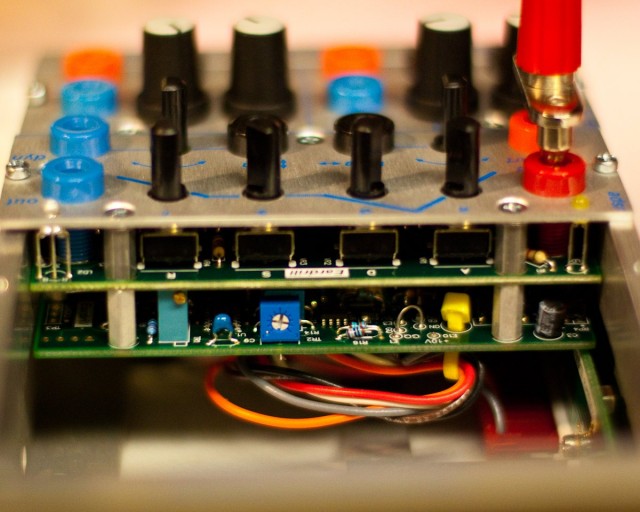

CDM guest and photographer Marsha Vdovin joins us for a photo essay. Given free reign to choose what she wanted to do, she visits a Buchla module maker. Photos can speak volumes, and here the beauty of Don Buchla’s synth designs come through, a decades-long legacy of open-ended, eminently-musical sound possibilities. So, too, does the craft of the custom Eardrill modules. Disclosure: while we loved both, a number of us preferred the Buchla 100-series modular to the Moog modular we had, learning synthesis for the first time back at my alma mater Sarah Lawrence. I’d love to see a Buchla versus Moog patch-off at Moogfest this year. Oh, and while I cheekily add this to our “Create Analog Music” series, the 200e is in fact a hybrid system. Analog and digital come together. It’s fitting.

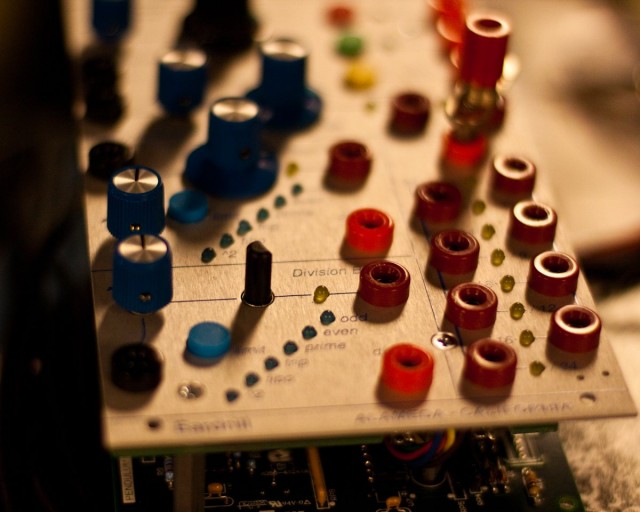

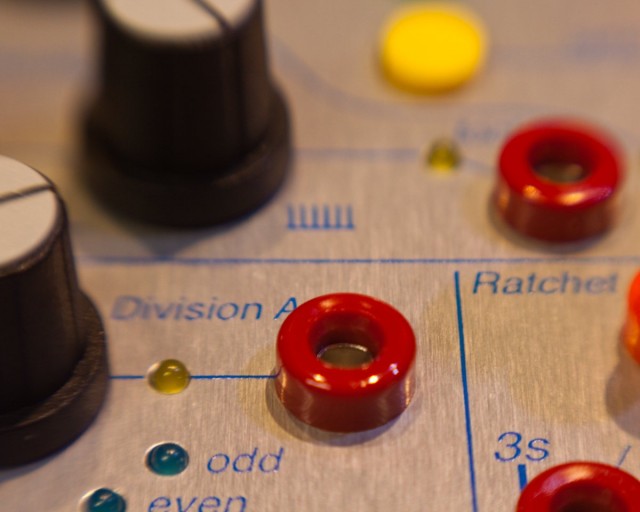

I recently visited my friend Chris Muir, a musician, engineer and all-around super-smart and fun person. Chris has a company called Eardrill and he handcrafts custom modules for Buchla 200 or 200e modular synths.

What was your first analog synth?

I learned on an ARP 2600, although the first one that I could call my own was an Oberheim SEM that I drilled out to bring out all the internal patch points. A band mate had a Minimoog in the dim, dark past, so I got to play with that quite a bit.

In college, I got introduced to the Buchla, and it was love at first sight. At the time, I couldn’t afford Buchla so I went with a Serge Modular, which at the time was known as the poor man’s Buchla.

I worked for Salamander Music Systems (SMS) in the late 1970s-1984, and really enjoyed working on making advanced synthesizers. I sold my Serge and got into a good-sized SMS system.

Why did you start making modules?

I worked in and out of the musical instrument industry for many years, then while waiting for a consulting gig to materialize, I thought it would be fun to get back into module making.

When I worked for Salamander, it was really fun seeing something go from an idea to reality. I love having a design on paper become three-dimensional “just” by working at it relentlessly. There’s something very satisfying about that.

Why do you use a Buchla 200?

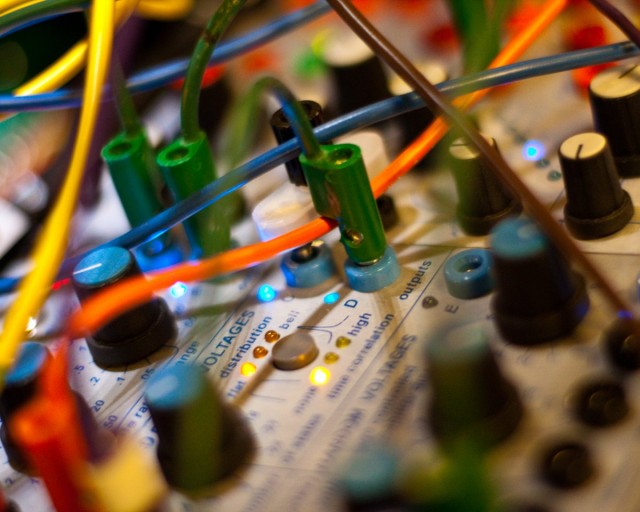

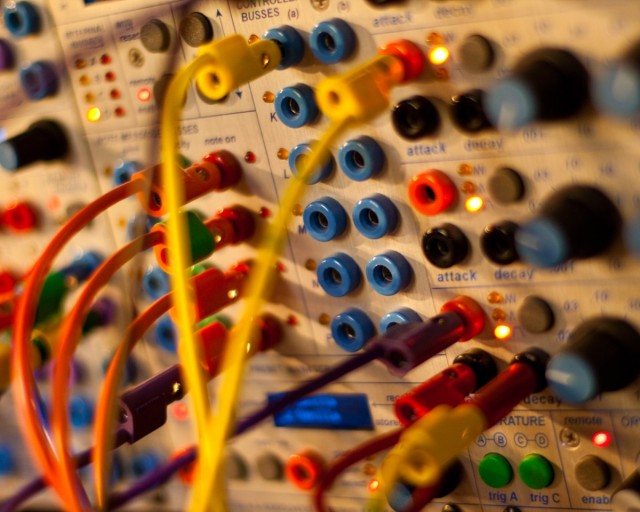

To me, the Buchla represents the road not taken. The question “what is a synthesizer” was largely answered in the marketplace by something resembling a Minimoog. Buchla was there at the beginning, following his own vision of what electronic instruments should be. The Buchla instruments emphasize workflow, and put a lot of musically interesting controls under your fingers. Most parameters on a Buchla can be voltage- controlled, so large-scale control structures can be realized. I resonate with the ideas behind it.

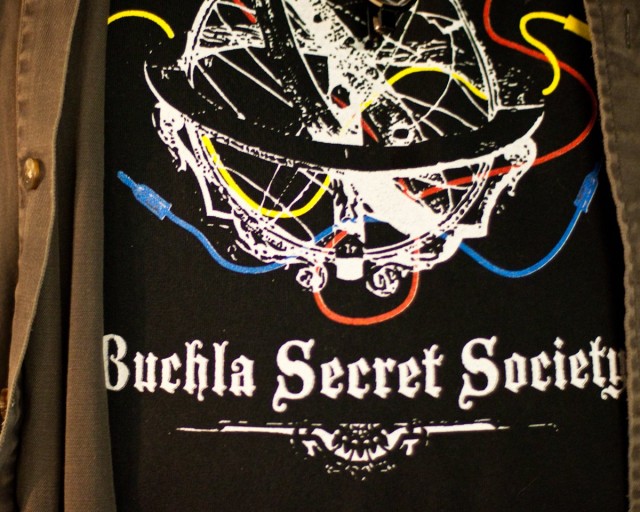

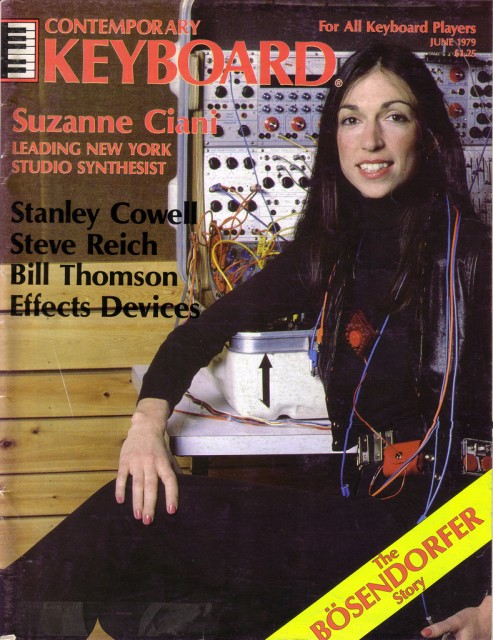

Buchla Love

Some more Buchla love seems an appropriate way to close this story. -Ed.