What you’re watching in the video above doesn’t involve cameras or motion sensors. It’s the kind of brain-to-machine, body-to-interaction interface most of us associate with science fiction. And while the technology has made the occasional appearance in unusual, niche commercial applications, it’s poised now to blow wide open for music – open as in free and open source.

Erasing the boundary between contracting a muscle in the bio-physical realm and producing electronic sound in the virtual realm is what Xth Sense is all about. Capturing biological data is all the rage these days, seen primarily in commercial form in products for fitness, but a growing trend in how we might make our computers accessories for our bodies as well as our minds. (Or is that the other way around?) This goes one step further: the biological becomes the interface.

Artist and teacher Marco Donnarumma took first prize with this project in the prestigious Guthman Musical Instrument Competition at Georgia Tech in the US. Born in Italy and based in Edinburgh, Scotland, Marco explains to us how the project works and why he took it up. It should whet your appetite as we await an open release for other musicians and tinkerers to try next month. (By the way, if you’re in the New York City area, Marco will be traveling to the US – a perfect chance to collaborate, meet, or set up a performance or workshop; shout if you’re interested.)

CDM: Tell us a bit about yourself. You’re working across disciplines, so how do you describe what you do?

Marco: People would call me a media and sound artist. I would say what I love is performing, but at the same time, I’m really curious about things. So, most of the time I end up coding my software, developing devices and now even designing wearable tech. Since some years now I work only with free and open source tools and this is naturally reflected in what I do and how I do it. (Or at least I hope so!)

I just got back from Atlanta, US, where the Xth Sense (XS) was awarded the first prize in the Margaret Guthman New Musical Instrument, as what they named the “world’s most innovative new musical instrument.” [See announcement from Georgia Tech.]

It’s an encouraging achievement and I’m still buzzing, specially because the other 20 finalists all presented great ideas. Overall, it has been an inspiring event, and I warmly recommend musicians and inventors to participate next year. My final performance:

Make sure to use a proper soundsystem [when watching the videos]; most of the sound spectrum lives between 20-60Hz.

Music for Flesh II live at Georgia Tech Center for Music Technology, Atlanta, USA, February 2012. Photo courtesy the artist.

You’re clenching your muscles, and something is happening – can you tell us how this XS system works?

Marco: My definition of it goes like “a biophysical framework for musical performance and responsive milieux.” In other words, it is a technology that extends some intrinsic sonic capabilities of the human body through a computer system that senses the physical energy released by muscle tissues.

I started developing it in September 2011 at the SLE, the Sound Lab at the Edinburgh University, and got it ready to go in March 2011. It has evolved a lot in many ways ever since.

The XS is composed of custom biophysical sensors and a custom software.

At the onset of a muscle contraction, energy is released in the form of acoustic sound. This is to say, similarly to the chord of a violin, each muscle tissue vibrates at specific frequencies and produces a sound (called Mechanomyographic signal, or MMG). It is not audible to human ear, but it is indeed a soundwave that resonates from the body.

The MMG data is quite different from locative data you can gather with accelerometers and the like; whereas the latter reports the consequence of a movement, the former directly represents the energy impulse that causes that movement. If you add to this a high sampling rate (up to 192.000Hz if your sound card supports it) and very low latency (measured at 2.3ms) you can see why the responsiveness of the XS can be highly expressive.

The XS sensors capture the low-frequency acoustic vibrations produced by a performer’s body and send them to the computer as an audio input. The XS software analyzes the MMG in order to extract the characteristics of the movements, such as dynamics of a single gesture, maximum amplitude of a series of gestures in time, etc.

These are fed to some algorithms that produce the control data (12 discrete and continuous variables for each sensor) to drive the sound processing of the original MMG.

Eventually, the system plays back both the raw muscle sounds (slightly transposed to become better audible, say about 50/60Hz) and the processed muscle sounds.

I like to term this model of performance biophysical music, in contrast with biomusic, which is based on the electrical impulses of muscles and brainwaves.

By differently contracting muscles (which has a different meaning than simply “moving”) one can create and sculpt musical material in real-time. One can design a specific gesture that produces a specific sonic result, what I call a sound-gesture. These can be composed in a score, or improvised, or also improvised on a more or less fixed score.

The XS software has also a sensing sequencing time-line: with a little machine learning (just implemented few days ago) the system understands when you’re still or moving, when you’re being fast or slow, and can use this data to change global parameters, functions or to play with the timing of events. For example, the computer can track your behaviour in time and wait for you to stop whatever you’re doing before switching to a different set of funcions.

The XS sensors are wearable devices, so the computer can be forgotten in a corner of the stage; the performer has complete freedom on stage, and the audience is not exposed to the technology, but rather to the expressivity of the performance. What I like most about the XS is that is a flexible and multi-modal instrument. One can use it to:

- capture and playback acoustic sounds of the body,

- control audio and video software on the computer, or

- capture body sounds and control them through the computer simultaneously.

This opens up an interesting perspective on the applications of the XS to musical performance, dance, theatre and interaction design. The XS can also be used only as a gestural controller, although I never use it exclusively this way. We have thousands of controllers out there.

Besides, I wanted the XS to be accessible, usable, hackable and redistributable. Unfortunately, the commercialized product dealing with biosignals are mostly not cheap and — most importantly — closed to the community. See the Emotiv products (US$299 Neuro Headset, not for developers), or the BioFlex (US$392.73). One could argue that the technology is complex, and that’s why those devices are expensive and closed. This could make sense, but who says we can’t produce new technologies that openly offer similar or new capabilities at a much lower cost?

The formal recognition of the XS as an innovative musical instrument and the growing effort of the community in producing DIY EEG, ECG and Biohacking devices are a clear statement in this sense. I find this movement encouraging and possibly indispensable nowadays, as the information technology industry is increasingly deploying biometric data for adverts and security systems. For the geeky ones there are some examples in a recent paper of mine for the 2012 CHI workshop on Liveness.

For those reasons, the XS hardware design has been implemented in the simplest form I could think of; the parts needed to build an XS sensor cost about £5 altogether and the schematics looks purposely dumb. The sensors can be worn on any parts of the body. I worked with dancers who wore them on the neck and legs, a colleague stuck one to his throat to capture the resonances of his voice, I use them on the arms or to capture the pumping of the blood flow and the heart rate.

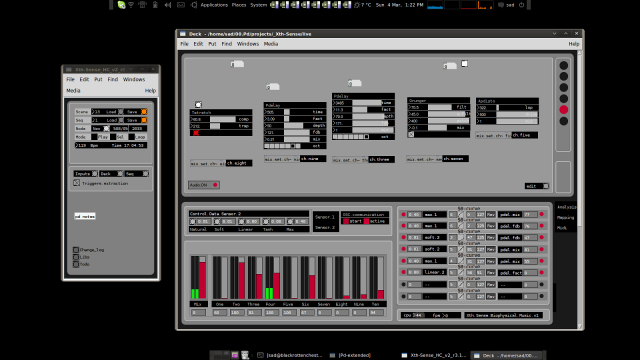

The XS software is free, based in Pd, aka Pure Data, and comes with a proper, user-friendly Graphical User Interface (GUI) and its own library, which includes over one hundred objects with help files. It is developed on Linux, and it’s Mac OS X compatible; I’m not developing for Windows, but some people got it working there too. A big thumb up goes to our wonderful Pd Community; if I had not been reading and learning through the Pd mailing list for the past 5 years I would have never been able to code this stuff.

The public release of the project will be in April. The source code, schematics, tutorials, will be freely available online, and there will be DIY kits for the lazier ones. I’m already collecting orders for the first batch of DIY kits, so if anybody is interested please, get in touch:

http://marcodonnarumma.com/contact

I do hope to see the system hacked and extended, especially because the sensors were initially built with the support of the folks at the Dorkbot ALBA/Edinburgh Hacklab. I’m also grateful to the community around me, friends, musicians, artists devs and researchers for contributing to the success of the project by giving feedback, inspiring and sharing (you know who you are!).

Thanks, Marco! We’ll be watching!

More on the Work

http://marcodonnarumma.com/works/xth-sense/

http://marcodonnarumma.com/works/music-for-flesh-ii/

http://res.marcodonnarumma.com/blog/

And the Edinburgh hack lab:

http://edinburghhacklab.com/

Biological Interfaces for Music

There isn’t space here to recount the various efforts to do this; Marco’s design to me is notable mainly in its simplicity and – hopefully, as we’ll see next month – accessibility to other users. I’ve seen a number of brain interfaces just in the past year, but perhaps someone with more experience on the topic would like to share; that could be a topic for another post.

Entirely unrelated to music, but here’s the oddest demo video I’ve seen of human-computer interfacing, which I happened to see today. (Well, unrelated to music until you come up with something this crazy. Go! I want to see your band playing with interactive animal ears.)

Scientific American’s blog tackles the question this week (bonus 80s sci-fi movie reference):

Brain-Machine Interfaces in Fact and Fiction

I’ve used up my Lawnmower Man reference quota for the month, so tune in in April.