In the words of Yogi Berra, the future ain’t what it used to be. Drawing from futurist philosophy and the machine aesthetic of bands like Kraftwerk, the moment at which techno comes into the world is a seminal birth in the creation of the age in which we live. Its creative energy is focused a the nexus of technology and music, set against the impoverished landscape of Detroit as America’s industrial urban centers implode. And while we’ve lost the people who could tell the story of the creation of jazz, the people who created techno continue to play.

We’re fortunate to get a rich look at this story, and pioneering artists like Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson, and Derrick May, from Wax Poetics, the terrific music lovers’ magazine. That publication devoted an issue to dance music, January/February 2011, issue 45, available as a back issue.

From that issue, Andy Thomas recounts the development of Detroit techno, through the eyes of the people who built it.

Subscribe to the Magazine

You can subscribe to Wax Poetics from the US or elsewhere in the world. As a special promotion for the appearance of this story on CDM, you can enter a code for a free issue when you do. Type in:

FREE ISSUE/CDM

You’ll just need to hurry; the offer expires in one week.

Subscribe to Wax Poetics

waxpoetics.com

ELECTRONIC ENIGMA: The myths and messages of Detroit techno

By Andy Thomas

Wax Poetics issue 45; reproduced by permission

“The music is just like Detroit, a complete mistake. It’s like George Clinton and Kraftwerk are stuck in an elevator with only a sequencer to keep them company,” Derrick May famously proclaims in the liner notes to the pivotal 1988 compilation Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit.

Through a series of interviews during this time, May and Belleville High School friends Juan Atkins and Kevin Saunderson helped both codify and mystify the electronic music of ’80s Detroit. In the process, the Belleville Three—as they became known—created a manifesto that reached far beyond the postindustrial streets that had inspired them. In Stuart Cosgrove’s article “Seventh City Techno” in the U.K.’s The Face magazine in the same year, Juan Atkins rips up the deep musical roots of the city as he looks to the future of Detroit as a landmark in the sonic imagination: “Within the last five years or so, the Detroit underground has been experimenting with technology, stretching it rather than simply using it. As the price of sequencers and synthesizers has dropped, so the experimentation has become more intense. Basically, we’re tired of hearing about being in love or falling out, tired of the R&B system, so a new progressive sound has emerged. We call it techno!” It’s been thirty years since writer Alvin Toffler coined the term “techno rebels” in his study of postindustrial society, The Third Wave. An avid reader of Toffler, Atkins did not have to think too hard for a name for this futuristic music when the journalists arrived to intellectualize the scene. But looking back almost a quarter of a century on, how much was techno actually a break from America’s Black musical heritage? And how discrete was it from the sonic experimentations bursting out of neighboring underground dance scenes?

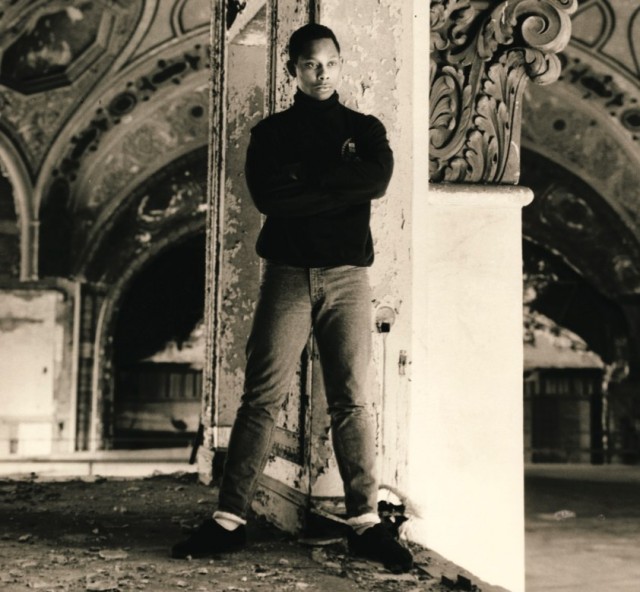

In a scene from the independent French documentary Universal Techno, Derrick May, surveying with camera in hand, snaps away at the worn grandeur of the disused Michigan Theatre like an inquisitive tourist. As his lens moves down the elegant arches, the image jolts as you witness the reality of the situation. “Inside this building was a theater, and they tore out the theater and they made a car park,” he laments. “So you are parking your car in a theater. And it’s fucking scary… I mean, look at these arches. They’ve been broken off, totally destroyed.” Visibly moved, he states with a quiet intensity: “Being a techno-electronic-futurist, high-tech musician, I totally believe in the future, but I also believe in a historic and well-kept past. I believe that there are some things that are important. Now maybe this is more important like this, because in this atmosphere, you can realize just how much people don’t care, how much they don’t respect—and it can make you realize how much you should respect.” This poignant scene from the documentary not only characterizes the planning decisions that have blighted Detroit but also typifies the devotion to the city by its musical futurists, who have sought sanctuary from the decimation through the soul of the machine.

“The general attitude here with the powers-that-be is that industry must die to make way for technology,” explains Juan Atkins, in the same film, sitting before a backdrop of empty buildings typical of inner-city Detroit. “The climate has definitely affected us, and I think that we probably wouldn’t have developed this sound in any other city in America… There is a certain atmosphere here that you can’t find in any other city that lends to the technological movement.” To feel the atmosphere of the city in the ’80s, you only have to look at some of the economics and the conditions that allowed a once prosperous town to crumble. No American city was as tied to one industry as Detroit was to car manufacturing. The realization of Henry Ford’s dream had led to a huge increase in industrial production. Between 1900 and 1930, Detroit’s population soared from less than 300,000 to over 1.5 million, the vast majority of the new workers employed in the car plants such as at Ford and General Motors. At the same time, under the direction of Albert Kahn, downtown Detroit became home to elegant structures like the art deco Fisher Building and cultural institutions such as the Detroit Institute of Arts. However, by the mid-’60s, just as the hits factory of Motown promised better times, the stark reality was that the automation of the car industry (from which the label took its name) and the movement of remaining plants outside of the city were ripping the heart out of Detroit’s center.The downturn became personal when Interstate 75 ripped apart the cultural hub of the Black Bottom neighborhood, Detroit’s own Harlem. With the economics compounded by increasing police oppression, the tensions boiled to the surface, and in July 1967, what be- came known as the Twelfth Street riots resulted in the death of forty-three people and the destruction of over 1,500 buildings. It was in Detroit’s Cobo Hall where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. gave an earlier version of his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. But that dream seemed a long way off, and by the mid- ’70s, Detroit’s center had become a post-urban ghost town with boarded-up shops and crumbling buildings. This backdrop, though, would inspire an alternative culture whose influence would be felt far and wide—as new technology aroused a bold new vision of the future.

It’s a romantic image perhaps, but one that rang true for any young music lover brought up in the Detroit area in the early ’80s—teenagers hiding under the covers on a school night listening to the life-changing signals being transmitted by Charles Johnson, a DJ known as the Electrifying Mojo, whose Midnight Funk Association radio show can rightly claim to have shaped the social and cultural development of a generation of music lovers in southeastern Michigan. “Mojo’s show was monumental in every single way you can imagine,” reflects Derrick May nearly thirty years on. “It was unique. FM radio was still very, very new and in its experimental stage. It was free and open, and anyone could listen to it. And a guy like Mojo came on the radio to do what he wanted to do, how he wanted to do it.” The music he played was radical and far-reaching, mixing up Parliament-Funkadelic, Prince, and Zapp with the alternative rock of the B-52s and Talking Heads, and importantly, the alien electronic music of Kraftwerk and other Euro- pean futurists like Telex and Japan’s Yellow Magic Orchestra. “He was more album orientated,” adds Juan Atkins. “You could hear him play half an hour of James Brown, and then after that, play half an hour of Peter Frampton. You know what I’m say- ing? He would go off on tangents like that.”

While the authorities did their best to break up the community, The Midnight Funk Association responded with music as a weapon, and a communal force. Harold Mansfield, whose Midnight Funk Association website is dedicated to the memory of the show, recalls how it united all those who listened: “At the top of the show, Mojo opened membership to the MFA, and members new and old were asked to stand up to show solidarity [with the immortal line: ‘Will the members of the Midnight Funk Association please rise’]. If you were driving, you were to flash your headlights. If you were at home, you turned on your porch light. If you were in bed listening to the show, you were required to dance on your back. And every night for years, people did it. To become a card-carrying member of the MFA, listeners wrote into the radio station and would receive their official ID card.”

Kevin Saunderson recalls how the friends eagerly consumed the music and messages from their radios in their suburban bedrooms: “It was kind of like a cult. We would listen to him religiously every night. He provided the youth with a positive direction and a new kind of energy.” From leafy Belleville, the three friends took a studious pleasure in analyzing the music. “We used to sit back and philosophize about what these people thought about when they made their music,” Derrick May says in Simon Reynolds’s book Generation Ecstasy. “We’d sit back with the lights off and listen to records by Kraftwerk and Funkadelic and Parliament and Bootsy and Yellow Magic Orchestra.” May now recalls, “We thought it was really cool and almost animated. We’d go to the record shops and look at the sleeves and be entranced by the artwork alone, and we’d just fantasize about what the records would sound like.”

Juan Atkins had already glimpsed the future when he heard the Mothership land over the airwaves with his music-loving grandmother who raised him: “I first heard Parliament-Funkadelic on the radio, tracks like ‘Funky Dollar Bill’ and the Mag- got Brain album… I think I was in elementary school when I first heard ‘Loose Booty’ [off the visionary 1972 LP America Eats Its Young]… The first time I actually saw anyone play a Minimoog or Korg MS-10 was Bernie Worrell.” While Detroit techno would stake a claim for a bold new future, it could be argued that it was also continuing a line of Afrofuturism that reached back to not only P-Funk but also to the other- worldly music of everyone from Sun Ra to Lee Perry. And rather than doing away with the “R&B system” under a post- soul future, cats like Juan Atkins were actually traveling the same progressive path as eminent voyagers like Stevie Wonder and Herbie Hancock; “Nobu” (a track from Herbie’s 1974 LP Dedication, recorded live in Tokyo nearly ten years before his prescient electro-jazz LP Future Shock) was “techno before the event that opens up a new plateau in today’s electronics,” according to Kodwo Eshun in his book More Brilliant than the Sun.

Despite acknowledging a great debt to this Black musical heritage, when Atkins bought his first piece of electronic equipment (a Korg MS-10 from the back room of a shop where his grandmother was having her Hammond B-3 organ repaired), it was to the mechanical soul of urban Germany that he looked. “I was really mesmerized by the precision of their music; everything was really robotic,” he explains on first hearing Kraftwerk. “Man—a light went on in my head.” While Kedwo Eshun recognizes techno’s debt to the Black futurism so evident in the progressive fusion of “Nobu,” he also notes in his book that for Atkins and his associates, “Kraftwerk are to techno what Muddy Waters is to the Rolling Stones, the authentic, the original, the real.” In truth, techno’s futuristic path probably began somewhere between Düsseldorf and

Detroit. In Dan Sicko’s book Techno Rebels, Kraftwerk’s Karl Bartos suggests as much when he explains the origins of their own influences: “We were all fans of American music: soul, the whole Tamla/Motown thing… We always tried to make an American rhythm feel, with a European approach to harmony and melody.”

The turn of the ’80s had seen kids in Detroit’s Black middle- class neighborhoods make up for the lack of cultural activi- ties in the city by creating their own network of parties, where aspirational fashions were the order of the day. “The scene was made up of lower-middle-class and upper-working-class Black people, basically preppy college kids wanting to be different,” remembers Saunderson. “They dressed a certain way and thought they were more important than they were.” Derrick May, whose first experience of clubbing was through the athletics club where he was a member, agrees: “It was really a highfalutin thing, really just for kids who lived in a certain community. Rich Black kids from places like Palmer Woods and Indian Village.” However pretentious and cliquey the scene might have been, it revolved around some forward-thinking music. “Although it was college based, the music was very progressive,” recalls Saunderson. “A mix of disco with lots of European stuff, especially all the Italian.”

The scene was epitomized by the influential party Charivari, where the soundtrack was a diverse mix of European and American dance forms. As Sicko explains in his book, European new wave and Italo disco “became the most popular music of the high school set.” The writer goes on to make the case that Italian dance groups such as Kano were actually every bit as important to the development of the early techno sound as Kraftwerk and Yellow Magic Orchestra. Witness the archive footage from The Scene, Detroit’s take on Soul Train, and you’ll see how huge Italo disco was for Black dancers in the city in the early ’80s. Such was the influence that what is often credited as the first techno record, “Sharevari” (produced by a Number of Names, a group of regulars off the high school scene) borrowed heavily from the B-side to Kano’s hit “I’m Ready.” “Detroit DJs would work two copies of ‘Holly Dolly,’ repeating the sparse intro over and over again and doubling up on the chorus,” explains Sicko. “A Number of Names mimicked this interpretation.”

At the same time around 1981, as the high school scene dominated Detroit nightlife, May and Atkins joined forces with their friend Eddie “Flashin” Fowlkes and started the DJ and party collective Deep Space Soundworks, which Saunderson would later join in ’84. With competition intense, the friends had to learn quickly both in terms of technical skills and also branding. May recalls to Sicko how their parties were as conceptual as the music they were playing: “We had amazing flyers back then, [which contained] these subliminal messages of an alternative way of thinking. We were trying to attract people that wanted to be alternative and wanted to be different.”

At the same time as A Number of Names was concocting its sonic landmark, Atkins had spent 1980 experimenting with the equipment his friend Rick Davis, a Vietnam veteran, had collected as an avant-garde electronic musician with a penchant for numerology and mysticism. “I went into his room, and it was like going into a spaceship,” Atkins recalls. “All you could see was the LED lights flashing. It was like I’d stepped into a whole new dimension.” Taking the name Cybotron from a term used by Alvin Toffler, the pair firmly saw themselves as techno rebels providing the soundtrack to an alternative future—where the people reclaimed technology for the benefit of the community.

While the pricing of electronic keyboards in the ’70s had been out of reach for all but the most established of musicians, by the early ’80s, the speed of technological advancements meant keyboards and synthesizers were quickly outdated. All of a sudden, drum machines and synthesizers became afford- able, and Atkins and his peers became fascinated by them. “I just liked the weird sounds,” he says, “the UFO and spaceship sounds you could make. So I was mainly into the synthesizer not so much for musical stuff but more for effects. But then I realized that it was dependent on how you tune the filters. You could tune the filter to make it sound like drums, snare sounds, or a hi-hat. So I would just combine all these sounds and ping- pong between my cassette deck.” But it wasn’t just Detroit’s young music obsessives who were accessing this cheap technology. Listen to Cybotron’s early records like “Clear” and “Alleys of Your Mind,” and you are reminded not only of their debt to Kraftwerk and Funkadelic but also of the similarities with the electronic music coming out of New York’s outer boroughs. Atkins was in New York City when Afrika Bambaataa and the Soul Sonic Force burst across the airwaves like a futuristic flash. “It was a very bittersweet type of thing,” he tells writer Sheryl Garratt in her book Adventures in Wonderland: A Decade of Club Culture, “seeing something along the lines of what I was doing go national like that.” While New York claimed the electro crown, the stark machine soul of Cybotron would be an important building block for Detroit techno, helping to dis- tinguish it from the sonic reverberations of mid-’80s Chicago. “That was the beginning for me,” reckons Saunderson. “Right there with that electro sound [with] which we would go on to build on and create our own thing.”

Although much has been made of the intellectualization of Detroit techno, in truth, the music of the early pioneers was made for the feet rather than the head. While the Belleville Three did take an academic approach to the consumption of music, they were all avid clubbers who had been inspired by Ken Collier, the godfather of Detroit dance music and, in particular, the city’s gay club scene. “He had a mix show on WDRQ,” recalls Derrick May, “and Juan came to me and said, ‘Hey, man, there’s this guy on the radio, and you’ve got to hear what he’s doing—he’s mixing records on the radio.” While Collier is considered to be something of an underground disco and house-music legend whose name evokes reverence in anyone who heard him spin, his name is often missing in the history of dance music in America. “It’s because it’s Detroit and the fact that it’s not one of the major music markets. And it’s also this very superficial, very, very jaded country and the way it sees things,” suggests May. “Our media decides to leave out the facts and doesn’t even try to find out what is the real story, what is the scene behind the scene, who was really important.”The truth is that Collier’s time behind the decks at clubs like Chessmate and Todd’s (alongside his brother Greg) in the late ’70s and early ’80s, as well as his later tenure at Club Heaven, were as important for Detroit as Ron Hardy’s tenure at the Music Box in Chicago or Larry Levan’s at the Paradise Garage in New York. “I would say Ken was important to the whole ecosystem of the music in Detroit,” May states thought- fully. “Without him, Darryl Shannon would not have existed. Without him, Delano Smith would not be here.”Shannon was an influential progressive DJ renowned for his mix of music at parties like Charivari, while Smith was another much-overlooked figure who played alongside his mentor Collier at both L’Uomo and the Downstairs Pub. “Without [Collier],” May continues, “there are music scenes that would not have happened, because he opened the doors for all those guys to learn how to be DJs.”Chez Damier,who had arrived in Detroit from his hometown of Chicago, also sees Collier as a pivotal figure in the city’s club scene. “He was very, very important to dance music in Detroit,” he states. “Because he had the gay kids as well as the straight kids—so he inspired everyone, really.”

Derrick May also regularly made the trip to Chicago, where Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles were bringing down the walls at the Music Box and the Power Plant respectively. “Frankie was really a turning point in my life,” May explains to Sicko. “When I heard him play, and I saw the way people reacted, danced, and sang to the song… This vision of making a moment this euphoric…it changed me.” However, the energy of Ron Hardy had even more of an impact on the aspiring DJ: “That blew me away. The first time I went to the Music Box, I lost my mind, I truly did. I was dancing like crazy, I was emotional, and almost in tears. I had never felt that power and emotion from the human soul all at once. All these people were feeling the same thing. It was as if they had been touched by the Holy Ghost… To hear the crowd screaming and calling Ron Hardy’s name, to go in there the first time and to wit- ness these people the way they were dancing and screaming his name. And to see Ron with no shirt on and playing with his eyes closed, just in it, and lost in the music. Man, it was the most important moment of my young life towards develop- ing and becoming a musician and DJ… How he slipped and twisted records and the edits he did and all the shit he was doing—it was psychotic.”

Detroit’s musical pioneers maintained close ties to their neighbors. Chez Damier, who was raised in Chicago but became a key figure in the Detroit techno scene, explains: “The dance music from Detroit and Chicago both came from the soulful disco sounds coming out of New York combined with the electronic music from Europe. At the same time, both cities have such a strong Black musical tradition that it was inevitable that when this new technology became affordable, they would both give birth to such strong electronic dance music.” Ron Hardy would use Detroit tracks in his sets, alongside those of the European futurists who had inspired them. And while the argument continues about which city laid down the first electronic dance tracks, Saunderson admits that ultimately the scenes developed in tandem: “At the time, I think we were really running neck and neck with Chicago. We had a relationship with most of them, you know, Farley [ Jackmaster Funk], Chip E., most of the guys. And so when we started to take our records there, they would all play them.” Chez Damier recalls dropping off Juan Atkins’s first solo release with Hardy. “We brought the test pressing of ‘No UFO’s’ to CODs where Ron Hardy was playing, and to our surprise, he played both sides. And we completely freaked out.” Such were the ties that during one of their trips to Chicago, Derrick May gave Frankie Knuckles the 909 drum machine that he’d use to create beats to bolster old disco records at the Power Plant and that would be featured on some of the first house productions by the likes of Chip E.

At the same time as Chicago’s early house pioneers had the infamous Trax label to release their DIY beat tracks, Atkins used “No UFO’s” to launch his own small imprint, Metroplex. There was a vision and direction to his art that inspired those around him, in particular a young May. “If Atkins was the prophet, the one to tap into the unseen and unheard possibilities of electronic music, Derrick May was the high priest who brought them about with forceful incarnations,” claims Sicko. In 1986, May launched Transmat, taking its name from one of Atkins’s techno-speak terms and originally planned as a subsidiary of Metroplex. “Juan has been the most integral part of the whole thing; without him it really doesn’t happen,” May fondly admits in Sicko’s book.

While “No UFO’s,” released under the name Model 500, sat somewhere between the electro of Cybotron and the jack- ing DIY music of mid-’80s Chicago, May launched Transmat with a track that really started to define a new sound for Detroit. Released under Rhythim Is Rhythim in 1987, May’s “Nude Photo” (co-written by Thomas Barnett) “represented a totally different approach from that taken by Chicago house— closer to the vest and definitely more personal,” writes Sicko. Saunderson is eager to give credit where it’s due for the dis- tinctive sound of early techno: “I think Mojo influenced us greatly. We had a more European sound, and that came from him. He opened our ears and made us believe we could play this music… I mean, if you listen to [my first release under the Kreem moniker] ‘Triangle of Love,’ it’s really a New Order bass line. It’s got the same chord progression.”

If anyone was to epitomize the sound of early Detroit techno, it was Derrick May. While “Beyond the Dance” furthered the stark atmospherics of “Nude Photo,” his next track, “Strings of Life” (co-written with Michael James), revealed a classicism and refinement that placed the electronic music of the city apart from the more raw, beats-driven sound of early Chicago house. Drawing incredible warmth from the cold- ness of the machine, May’s early productions as Rhythim Is Rhythim were as haunting as they were uplifting—creating a fitting soundtrack to Detroit’s post-urbanization. At the same time, if one wants to hear where the jazz of Detroit went after labels like Tribe, one only has to lend an ear to the man who has been called, maybe somewhat lazily, “the Miles Davis of techno.”

If the appetite of May and Atkins for high-energy tracks and stark beats had been the result of nights dancing at the Music Box, it was at New York’s hallowed Paradise Garage where Saunderson had received his education. “The Garage influenced me subconsciously,” he explains. “When I went into this big room and heard that huge sound system, it changed the way I heard the music. When you listened to the radio, you heard things like ‘Good Times’ and ‘Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now,’ but at the Garage, it would sound different because of the way Larry [Levan] played it. He would just keep the mu- sic going and stretched it out, playing these incredible vocal tracks.” Although releases on Saunderson’s own KMS label and under his Reese moniker could be as deep and dark as any of the early techno tracks (with the brooding “Reese bass” becoming a staple sound in drum and bass), his love of New York garage and what became known as “deep house” brought out the soul in the young producer. “I had always loved the great divas like Chaka Khan and Jocelyn Brown,” Saunderson continues. “And hearing Larry play the music in that way made me want to make underground Detroit music but with vocals, just using the tools I was used to instead of the full band on those records I loved from the Garage.” Just as instrumental tracks like “Strings of Life” became anthems in the fields and warehouses of England during the late-’80s acid-house boom, Saunderson’s soul-drenched releases “Good Life” and “Big Fun” (under the Inner City moniker) stormed the clubs and the charts across Europe. “It happened so quickly,” recalls Saunderson, who became a regular at Spectrum in London and the Hacienda in Manchester when he toured with Inner City in the U.K.

Such was the boom in Detroit’s electronic music scene that 1486–1492 Gratiot—the street where the studios of Metroplex, Transmat, and KMS were located—became known as “Techno Boulevard,” as the city’s music scene experienced a boom not seen since the days of Motown. Interestingly, it was Motown fanatic Neil Rushton from Birmingham, England, who was to make the journey to Detroit to check out the scene and to instigate the release of the first and most influential techno compilation, the aforementioned Techno! The New Dance Sound of Detroit on the Virgin subsidiary 10 Records. Sheryl Garratt recalls in her book that when Rushton arrived back at Derrick May’s home studio loaded with soul 45s, the young host had to tell his guest to “turn the crap off.” As Rushton explains, “Mute Records [English label home to Depeche Mode and Yazoo] had been much more of an influence on them, than say Stax.” But it was this northern-soul lover with the help of eager British journalists that broke Detroit techno to the masses. “He has done so much for us, and I think he kind of gets knocked out of the loop a bit,” says May thoughtfully. “The guy discovered us. We were making music, but he brought us together and unified us and gave us the opportunity to attack the world and send our message out.”

In the same year that techno was exploding onto the dance floors of Europe, the scene finally had a place to call home with the opening of a new club at 1315 Broadway, the Music Institute. “I think we captured magic in a bottle,” states May. “The timing was perfect. I had my radio show and had really honed my skills as a DJ. Jeff Mills was doing his thing. Kevin, Juan, and myself were making those records. All this was happening at the same time, and then the club opened… It was unbelievable.” Opened by George Baker, Chez Damier, and Alton Miller in the spring of 1988, the club became a sanctuary for Detroit’s alternative community. “It had a profound effect on the city’s development, culturally,” says May, who like all of Detroit’s electronic music makers had been waiting for a truly egalitarian space for their culture to grow. “The MI was important because it took our scene to the next level,” adds Saunderson. “[With] all that stuff that had been happening in New York and Chicago for years, it gave us our own version of that. It was definitely our Music Box or Garage.”

A former coat-check boy at the MI and now producer and label owner of NDATL Muzik—which has just released a series of old unreleased MI classics—Kai Alcé goes one step further: “Well, at that time, there was no ‘techno’ scene really; just a few house/club parties thrown by party groups such as Charivari and other groups like it. But as far as for Derrick and those who were about to create what we now know as techno, there was no better testing ground.” Kai vividly recalls the excitement of those formative days: “Fri- days after school, I would go down to the club and we’d go through all the promos sent to the club and to KMS, which was down the block. Around midnight, the cool kids would start showing up in the parking lot and chilling, drinking, smoking, doing whatever in their cars. The line would some- times be long but always worth the wait… As you walked through the door, you saw the famous sign that is now the graphic on the first MI 12-inch. Then a right and quick left, and you are now in the future!”

Friday nights at the MI would open with D Wynn, Saunderson, or Atkins before May took to the decks at the height of his art. “Mayday was the star of the show,” enthuses DJ/ producer and MI regular Alan Oldham on the Hyperreal web- site. “Many times, he’d play tracks right off a Fostex two-track recorder that he’d just cut hours before at his studio, some- thing I never got over. He’d beat mix between the reel-to-reel and 1200s and back, using the pitch control on the reel. He’d cut, edit and destroy other people’s tracks, too, as he did with his fucked-up psycho re-edit of the MI theme ‘We Call It Aciiiieeed’ by D-Mob.” In an interview with Andy Battaglia in the A.V.Club, Carl Craig explains how the younger generation were inspired: “If he wasn’t Derrick May the producer and DJ, he would have been Reverend Derrick May, because he was so spiritual at the time, and into how the music related to what he felt and what he was doing—how the music can change the world… So there was a lot of teaching there, whether he was doing it on purpose or not.”

Chez Damier, who took care of Saturdays with fellow DJ Alton Miller, recalls the importance of the club to Detroit’s next wave of producers: “It was very much needed in Detroit at the time. Because it was a juice bar, it allowed kids to come in and experience the music. And through that, it raised a whole new crop of people.” Kai Alcé remembers how the club be- came a hotbed for Detroit techno’s second wave of producers and DJs: “Seeing folks like Carl Craig, Jay Denham, Kenny Larkin, Eddie Fowlkes, and Anthony Shakir on any given night and hearing them come up with their own sounds, but all stemming from this one vibe, was amazing.”

At the same time as the MI created a home for Detroit’s alternative arts scene, the likes of Derrick May grew increas- ingly opposed to how their music was being consumed in some quarters. “I don’t even like to use the term ‘techno’ because it’s been bastardized and prostituted in every form you can possibly imagine,” he explains in Generation Ecstasy, being particularly turned off by the heavy drug use on the European rave scene. Eddie Fowlkes, who had been a con- stant companion of the Belleville Three throughout the ’80s, went so far as to title his 1996 album Black Technosoul to reconstruct the links.

If the approximation of techno became in many cases a watered-down or misrepresented version of the raw electronic soul of the original pioneers, back in Detroit, the second wave went deep. At the head of the pack, Carl Craig took the jazz influences that ran through the work of Derrick May to the next level with releases on his own Planet E label such as Innnerzone Orchestra’s “At Les” and “Bug in the Bassbin,” a journey that would lead to his recent collaboration with elders from Tribe Records.

While Music Institute regulars Richie Hawtin and John Acquaviva’s Plus 8 label continued in the vein of Transmat and Metroplex, the ’90s also saw a more hard-core form of techno both in sound and appearance emerge from Detroit. If Der- rick May was the Miles Davis of techno, Mike Banks was its Archie Shepp. Rallying against the commercialization of their culture, Underground Resistance, the label Banks started with Jeff Mills, became a breeding ground for militant yet moving electronic music. Retreating deep into the underground, UR brought some much needed mystique to a scene that was in danger of suffering vertigo after its sudden ascent. “There’s a very strong, individualistic mentality here in Detroit,” the elusive Mike Banks explains in a rare interview in 1992. “You develop it without even noticing. I didn’t notice until I went overseas, where everyone has several really close, dear friends. Here, it’s like Vietnam—I’m not getting close to anyone.” The UR uniform became as militant as their music with Banks’s regulation army boots and flight jackets drawing comparisons with another crew fighting the power through music. The Un- derground Resistance collective created no-holds-barred, syn- apse-crushing slabs of electronic music with names like “Riot” and “The Punisher,” and rather than celebrating their success, the makers decamped to their Detroit bunkers to radicalize their art.

Equally as suspicious of the industry and the commodifying of their culture were producers like Kenny Dixon Jr. (aka Moodymann) and the Three Chairs collective of Theo Parrish, Rick Wilhite, and Marcellus Pittman, whose deep productions of the mid-’90s represented for many what was a third wave of Detroit electronic music. As dedicated to preserving the arts in their hometown as the pioneers of original Detroit techno, these fiercely independent music makers would take Black electronic dance music back to its roots. As Theo Parrish claims, “The medicine in the dance is originally African.” At a time when much techno and house was being commercialized in the same way that R&B had been in the ’60s, figures like these were essential in reclaiming the soul of Black dance music. Whereas the original pioneers of electronic music in Detroit were sometimes penned in by the myth that had been created around their music, the understandably press-shy third wave refused to be boxed by media-friendly titles, producing instead what the Art Ensemble of Chicago termed just “great Black music.” But at the same time, in the music of Theo Parrish and Kenny Dixon Jr. and new heads like Omar S and Kyle Hall, we are hearing Black electronic funk that could only have come from Detroit.

As for the Belleville Three, they remain in Detroit and continue to produce breathtakingly raw and soulful electronic music both in the studio and behind the decks. While Detroit techno has, more than any other dance music, found itself intellectualized and analyzed to the point of distraction, the original pioneers have never lost their focus on what is, at the end of the day, music to move your soul and make you sweat. And like many Detroit music makers, they remain fiercely loyal to the hometown that shaped them. With Detroit “being isolated from the rest of the popular world, that whole pop culture didn’t really have a big impact. So there was none of that Andy Warhol–style phenomena,” concludes Derrick May. “The common man of Detroit, the working stiff, didn’t know anything about Warhol or Salvador Dalí, didn’t grow up having any off-Broadway productions; he didn’t have that. Detroit has had it [in the past], but the latter-twentieth-century man didn’t have it. So I think the impact of what happened is totally tied to the fact that it’s a city of improvisation. And that improvisation is more or less tied to an impoverished community that has had to find new ways of entertainment and new ways of survival. And I think you have to say that creates a subculture. It means that people have to look another way to find some sort of level of enjoyment, entertainment. Some sort of outlet, some sort of euphoria.”

-Andy Thomas

Playlist

Wax Poetics assembled a playlist for this issue, relevant both to this article and, well, with some good listening in general. Look it up and enjoy – or stream free and buy directly from their site.

Do It (‘Til You’re Satisfied) – B.T. Express

Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (JM 4AM Mix Pt. 1) – Inner Life

Dance and Shake Your Tambourine – Universal Robot Band

Hunk Of Heaven – Lemuria

Don’t Take My Shadow (A Tom Moulton Mix) [Extended] (A Tom Moulton Mix – Extended Vocal) – Kings Go Forth

Slipped Disc – Lizzy Mercier Descloux

Your Life – Konk

Crusader – Knightlife

Love Me Like This (Nonsense Dub) – Floating Points

Let’s Clean Up The Ghetto – Philadelphia International All-Stars