Cymatic ripple from flight404 on Vimeo.

It’s a beautiful age emerging for people making art with code. Tools like Processing and OpenFrameworks are as much about a philosophy and way of life as a specific tool. They’re not only about free and open code, but lightweight syntax, pulling together libraries that make media “just work,” and getting artists from just “tinkering” to making things happen, expressing ideas as quickly and efficiently as possible.

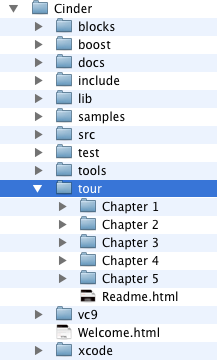

Robert Hodgin, Andrew Bell, and The Barbarian Group have been working on their own C++-based framework that’s at the core of the stunning work they’ve been doing. The site is currently private, but I decided rather than sit on the news (or procrastinate CDM’s own coverage), I’d give you a first look.

Updated: the site is now up and public!

http://libcinder.org/

Andrew Bell describes the project thusly:

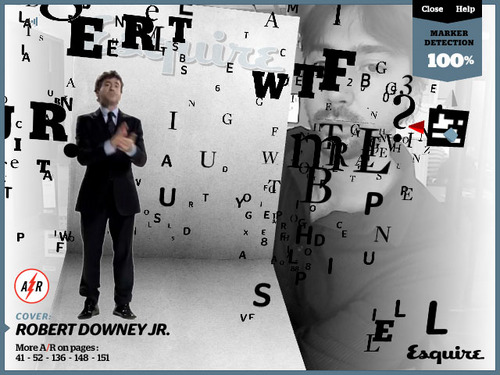

Cinder is the cross-platform C++ library we’ve been using for our client work at TBG for a while now – things like our iTunes visualizers, augmented reality project for Esquire magazine, and various art installations were all created in it. We are releasing it under the BSD license, so you can use it for both open source and closed, commercial development. It will be hosted on github soon, but you can download the packaged releases from the site now.

These are early days (this being our first release) so there are plenty of rough edges, but we’d love to hear what you think…

Project originator Andrew also writes back with some answers. Naturally, we’ll have more to look at as this is released. (We should also re-connect with the Processing and OpenFrameworks projects, too, perhaps even asking some of the same questions; as I say, the larger context and community matters as much as the particular tools.)

Peter: Can you talk a little bit about how this framework has evolved?

Andrew: Sure – Cinder began life as the in-house creative coding framework for The Barbarian Group. We originally developed it in conjunction with our Magnetosphere iTunes visualizer, to help us port Robert Hodgin’s music visualization experiments out of Processing. Soon other Barbarians got involved, which has been one of the huge advantages we’ve enjoyed – having TBG’s awesome development staff hacking on it has really accelerated Cinder’s development. Also we had a big boost from people I know through my background writing code for visual fx. I’ve had the very humbling opportunity to work with people who are or were at places like ILM, Rhythm & Hues, Psyop, The Mill and others. Many friends and former coworkers of mine have contributed advice or code to Cinder along the way. Their perspective has been invaluable, and Cinder would not be nearly as strong without their help. The visual effects and motion graphics world is one that doesn’t get a ton of attention from the mainstream creative coding community, in part because they are required to be much more quiet about their work. But some of the most extraordinary coders in the business are toiling away in that relatively closed world.

Our design philosophy behind Cinder has been to create the C++ framework that Robert (who when we started had written about 15 hours worth of C++) wanted to use, but also that I wanted to use (having written about 15 years worth). On the surface that seems sort of impossible, but there’s a happy coincidence you discover when you get into it. A beginning C++ programmer knows there are dark corners to avoid, but he’s not quite sure what they are. And someone who’s written as many C++ bugs as I have knows all about those dark corners, knows his own deep, personal failings as a coder, and wants a library that prevents him from having to ever worry about them again. I’m actually pretty proud of how close we are to that goal with Cinder.

Rembrandt Peale, portrait of Rubens Peale from flight404 on Vimeo.

What are your plans for it for the future?

Well, we’re just getting started here, so some of the core features like documentation are in real need of attention. Also our iPhone/iPad support is brand new and there’s a ton of features we want to cover there. We’ve got different developers interested in or already working on QuickTime exporting, OpenCL and CUDA support, a more sophisticated typographic engine, and more advanced 3D model and animation import/export. Beta users have already shipped Cinder projects which integrate OpenCV, Box2D and Bullet physics, but a priority is writing high quality bridges between those libraries and Cinder. I just unboxed a new multitouch panel tonight, so I’ll be working on adding Cinder support for that starting when I hit “send” on this email. Also on the long-term list are Linux support and a DirectX backend. That’s the stuff off the top of my head – I’m sure I’m forgetting things.

How do you expect others may get involved?

Well, going forward, our intention is quite simply to build a living, breathing community around Cinder. Kind of incredibly, TBG has turned control of Cinder over to the larger world of open source. If you ask me, that was a very bold move for a for-profit company, and my hat is off to the management for making it. The hope is that Cinder will become a rallying point for this sort of collaboration amongst not only individuals but also other companies doing creative coding work. Thus far, the response has been unbelievably encouraging.

We are now on github, so anybody can submit patches, and we are absolutely open to all kinds of contributions. One of our goals is for API designs to be thoroughly vetted by the community. We know from experience how hard it is to nail a good design out of the gate, so the hope is that Cinder will foster a collaborative community where users really examine, discuss and improve a design collectively instead of just committing the first design straight into the repository. Git is a great tool for facilitating that as well.

Also I mentioned creating bridges to 3rd party libraries, which is one of the most important ways we see others getting involved. We want to make sure Cinder remains lightweight and relatively free of external dependencies, and the techniques we use to integrate with other libraries are really key to achieving that goal. We’re hoping the first official integrations with OpenCV and Bullet will help the community develop some collective wisdom on how best to do it. And we’ve got some nice C++ strategies, several of which are already implemented behind the scenes in Cinder, to allow some really slick integration of 3rd party code without requiring users who don’t require something to be weighed down by it. Plenty more to come on this front.

What are some of the unique capabilities it has that have made it work in your work?

I think Cinder’s proudest moment to date was the augmented reality issue we did for Esquire magazine. That thing had an unreal number of moving parts. Tons of custom GLSL shaders, dynamic textures, QuickTime movies decompressing on a hardware accelerated path, a custom codec to let us do alpha channels on the fly with h.264 video, a custom-coded replication of Maya’s animation scene graph, OpenCV face detection, webcam capture, not to mention augmented reality marker detection, all often running simultaneously, frequently on multiple threads. We were able to get it running on tons of Macs and PCs out in the real world as a completely self-contained, installerless app and (to my knowledge) it doesn’t leak at all – not memory, not GL textures or other resources. And this despite the completely insane schedule it was developed under, with a team of coders working with very little sleep, some of whom were brand new to Cinder, is probably the strongest testimony to Cinder’s strengths. I’m not gonna lie – we’re pretty proud of how it held up.

How would you compare Cinder to something like (C++ framework, also geared for artists) OpenFrameworks?

Well let me caveat all this by saying that it’s been a little while since I studied OF in detail. I think it goes without saying that OF has some very sharp minds behind it. Also we’re friends with many of its core community. We have a ton of respect for the job those guys have done in terms of bringing C++ as a tool for creative coding to a much wider audience. They have also done an amazing job creating a bridge that that feels familiar for the Processing community in particular.

Ed.: Note that all these tools are friendly, so while the likes of Adobe and Apple trade barbs, back in the free software community, these developers mostly trade slaps on the back – and OF creators have already expressed their support for Cinder. There are clearly a lot of shared larger goals. -PK

There are clearly some overlaps between the two – obviously both are C++ libraries for creative coding, and there’d be a reasonable amount of intersection if you were to make a Venn diagram of their feature sets. We support roughly the same platforms, though OF supports older versions of Mac OS X than we do, and already has Linux support. However if you look at code that achieves roughly the same thing in both, you’ll find they have pretty different underlying design philosophies.

I think that looking at how the two libraries handle a normal task like loading an image into an OpenGL texture makes a good example. Starting with OF, you use the ofImage class’s loadImage() function to get things started. OF uses the FreeImage library, which is an open source library that supports loading around 30 or so different file formats – a pretty formidable number. So in OF, if you load an image say on the Mac, as a user you ask OF, “hey – I need you to open up whatever.png.” Then OF goes and asks FreeImage to load the file, which in turn does some of its own work and then decides to ask libpng (which is baked in to FreeImage) to handle it, then libpng does some of its own thinking, asks the operating system to do some disk I/O etc, and ultimately you get your PNG back as a collection of pixels. But it turns out Mac OS X (and Windows, and the iPhone OS) already know how to handle all the file formats most of us will ever need. Cinder makes use of these platform-native capabilities automatically. So in Cinder, you call the function (unsurprisingly also called) loadImage(), and it knows how to politely ask the operating system to load the file directly. This means if your operating system gets an upgrade, or a bug fix, or a security update, or learns about a new file format, all Cinder apps automatically benefit from it. This also means Cinder apps can be much lighter weight, since we don’t have to ship a bunch of additional libraries or the code to load file formats you never use with your app. As a final thought on this point, Cinder is designed so that if you do need to use an additional library for loading some unusual file format, you can integrate it as a first-class citizen, without modifying Cinder itself. The loading mechanism allows outside code to seamlessly integrate with functions like loadImage() just like Cinder’s own code does. We think designs like this will lead to some incredibly powerful addons for Cinder.

Continuing with the example, it turns out that ofImage contains both a memory-based representation as well as an optional OpenGL texture. In Cinder, we create a gl::Texture using the result of loadImage() as the constructor parameter, so it looks about like this:

gl::Texture myTexture( loadImage( "whatever.png" ) );

A big advantage there is that loadImage() and the constructor for gl::Texture know how to sort out between them an optimal representation based on the file itself, and without requiring an in-memory intermediary. So Cinder can do some very slick things automatically. For example, if your PNG happens to have 16-bit data (because it’s a normal map, for example) gl::Texture() can tell and will allocate an appropriate OpenGL representation so you don’t lose important data. It can do that for floating point high dynamic range images, as well as grayscale images. loadImage() also knows about things like whether your alpha is premultiplied or not. Some of these types of features are only important for advanced applications, so their absence from OF isn’t a big deal to some of its users. But for beginners, it’s nice to know they are happening automatically – Cinder provides a lot of power for free.

Continuing in the vein of image I/O, if you have the URL to an image you’d like to load over the network, that’s quite easy in Cinder too.

gl::Texture myTexture( loadImage( loadUrl( "http://libcinder.org/whatever.png" ) ) );

Pretty simple, consistent code – and all those earlier benefits apply equally to an image coming down from the network.

Going back to the design philosophy we were talking about earlier, things like proper exceptions, namespaces, modern memory management techniques like shared_ptr, etc. are not only the kinds of features experienced C++ users expect to see – in practice they actually make life easier for beginners as well. To be fair, there’s a bit more for a new C++ programmer to get their heads around initially, but our experience has shown people doing creative coding are plenty smart to handle it, and they take to features like those incredibly quickly.

Now all that said, it’s important to keep in mind that we also just released our very first version today, while OF has been out for a good while now. Many of these ideas are subtle – they don’t show up in the bulleted feature lists, and some of them take first-hand experience with both libraries to identify. Quite frankly, we’ve got a long way to go. We are definitely excited about where things already are, but where Cinder is heading is far more interesting.

Addition/Subtraction from flight404 on Vimeo.

Thanks, Andrew, Robert, and to everyone at The Barbarian Group – congratulations on this first release. Stay tuned; we’ll have more news soon, and talk to Robert more about some of the art-making and creative process behind working with this tool.