The transformation of expression in digital form is not the magical outgrowth of some unseen force, nor the studied assemblage of minds to tackle a high-priority, high-profile problem (as was nuclear fission). It is the result of a handful of tinkerers, working on “what-if” research scenarios with little money or priority from their employers. They had no clear commercial application, indeed with no view of the radical transformation of culture they were about to unleash. The revolution, in other words, was a clever, challenging hack pulled off by people who were tenacious and smart about making stuff. And because so few did so much, you can actually learn their names and meet the people who made your tools possible.

Photographer David Friedman – a veteran photog from NYC who has a stunning series of portraits of inventors on his portfolio site – here visits Steven Sasson, the man who gave us the digital photo camera.

Inventor Portrait: Steven Sasson (Via Daring Fireball)

For yet more insights (if less artfully shot), see a 2010 interview by Kodak. Video:

Sasson, a Brooklyn-born electrical engineer, was given a simple challenge at Kodak. Could you make a camera out of solid state components and a CCD? We know the answer to that question in hindsight, of course. But at the time, it was no minor challenge. As Sasson told the Kodak company’s Plugged In blog in 2008:

It was a very small effort that started out as a general investigation of the imaging properties of CCD imagers that were just becoming available for experimentation. I thought it would be very interesting if I could build a still imaging camera around this new imager. From there I went to an all-digital implementation idea with the dream of demonstrating a camera that had no moving mechanical parts. I had no idea in the beginning how difficult it was to make this work, and if I knew, I might not have attempted it! It was a very small project with almost no budget and very few people knew we were working on it. We even had to clean out an unused back laboratory for some space. The situation was just about perfect to try something crazy.

See:

A Kodak Moment with Steve Sasson [Kodak Plugged In]

Steve Sasson & the World’s First Digital Camera at Chautauqua [Kodak A Thousand Words]

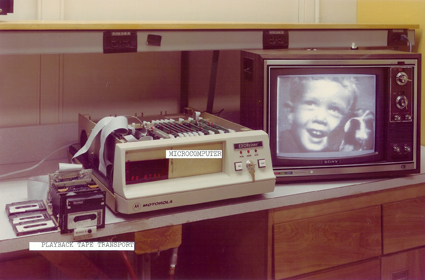

The result was a clunky but surprisingly functional camera. Yes, it recorded images to tape. And yes, Sasson even considered the quantity of exposures on a roll of film in limiting its storage capacity. But all the fundamentals of the modern camera were there, and the picture even looked decent.

It’s hard to fathom both the challenge of the task – or the momentous moment that would come, and just how far it would eventually lead. From the same interview:

I remember questioning my sanity for even thinking that I could ever get this to work. The CCD device was extremely temperamental, the timing of all the digital circuits had to be worked out by hand-drawn timing diagrams and the microprocessor used in the playback unit had to be programmed in assembler language. There were many days I wished I had taken a much smaller bite at this apple and perhaps just done a bench experiment measuring the parameters of a CCD in a test fixture. However, I had the support of two enormously talented technicians, Bob Deyager and Jim Schueckler. This project would not have been a success without them. I remember working day after day in the lab with Jim as we battled the demons in the prototype camera. I think we kept each other going. With a lot of luck and a great deal of help from many members of the laboratory we finally reached our goal of taking and displaying our first picture in December 1975. I remember being very happy and breathing a big sigh of relief that all of it worked.

And here’s what the first image looked like:

It’s also a sobering lesson in the power of disruptive technology. Kodak, in a tiny project with nearly no budget and no real strategic intention, unwittingly sowed the seeds of the end of their own company’s dominance in imaging. Disruptions don’t always come from without, in other words – sometimes they come from within. (Hmmm… actually, that’s a terrible argument for supporting research, so think of it another way: imagine where Kodak would have wound up had someone else developed digital photography first.) This, in turn, could explain why Kodak was painfully slow to develop the technology. (Whether that would have made their place in the digital world to come better or worse, I’ll leave you to decide.)

The story of Sasson is perhaps as revealing as the story of his camera. Here is a man who first-hand created one of the most significant inventions in modern technology – easily an Edison or Tesla of the 1970s. Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs are far better known, even though Woz didn’t invent the personal computer and Jobs wasn’t an engineer. Yet Sasson is relatively obscure. In fact, it wasn’t until Kodak themselves and a local newspaper picked up the story in 2001 that even most technologists knew that Sasson was the inventor of digital imaging as we now know it.

Of course, to really appreciate the motion aspect of this – and the origins of the CCD itself – you have to go back a little further.

The Birth of Digital Imaging: the CCD at Bell

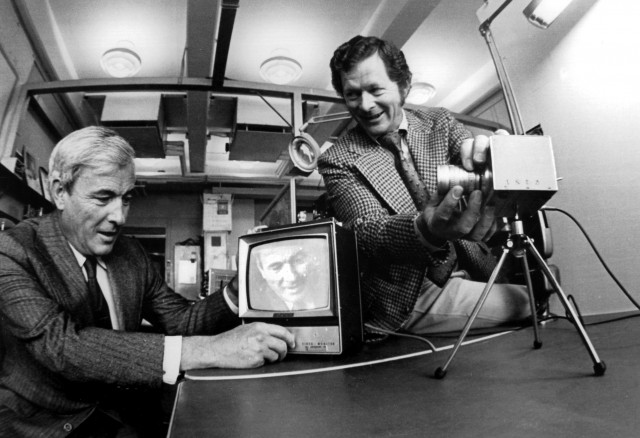

Without the Charged Coupled Device (CCD), neither digital photos nor video would be possible. And, bizarrely, video actually preceded the still image. Bell Labs, now Alcatel-Lucent, notes that their engineers, George Smith and Willard Boyle, deserve credit for creating the first digital video camera and the first working CCD. It was this invention that truly marks the move from film, from the chemical capture of photography, to a format that would work with digital.

In the fall of 1969 – the same season in which humanity first landed on the moon – they sketched out the ideas. By 1970, they had the first CCD video camera. By 1975, it was broadcast quality.

The technology arguably went on to do something that even overshadows the moon landing in achievement: with the images from space telescopes like the Hubble Space Telescope, photography not only changed perception, but changed our fundamental view of the universe in which we live.

Here’s a thought: between Max Mathews – creator of the first digital synthesizer – and Sasson and the Bell Labs CCD team, you have most of the content of these two sites. Add in Bernard Gordon, creator of the UNIVAC and the modern (high-speed) digital-to-analog converter, and Ivan Sutherland’s real-time vector graphics on Sketchpad, and you’ve got pretty much the whole deal. Sadly, a lot of the research environments that created such work – like Bell Labs – no longer exist, in favor of bringing products to market.

No disrespect to the Jobs and Gates of the world, but I hope in the long run the history of some of these original pioneers becomes better known. If we don’t begin to chronicle that history now, in this generation, it could be lost forever.

If such things interest you, amateur photo historian Rodger L. Carter’s site has a great look at the gradual evolution of all of the components on modern digital cameras. Surprisingly, a lot of it happened in the 1970s, if in piecemeal fashion:

http://www.digicamhistory.com/1970s.html