Complaining about pop music is probably the safest form of musical clickbait imaginable. After all, who isn’t annoyed by at least some earworm, some teeny-bopper celeb? If you long for still more of that, we have another white guy shouting at a camera about it – and, to be fair, some of this is reasonably funny. There’s just one problem: is the argument that music is getting progressively worse actually true – or even asking the most relevant questions?

First, let’s have a watch of the film:

The thesis that pop music is terrible and getting worse is not terrifically difficult to argue if you so choose, but Paul Joseph Watson takes up something that ought to read as more provocative right in the one-line description:

“The music industry is brainwashing us into liking terrible songs.”

I initially thought that the “brainwash” reference would have something to do with the production of pop songs – maybe something like the “four chord phenomenon,” where many chart-toppers have the same major triadic harmonic progression (with the same voicing, no less). Listen:

To me as a composer, this was always fascinating. In fact, rather than a criticism, you could watch the above video as something of a challenge – how do you fit in a harmonic structure so narrow, but stand apart? (Bonus irony points: “Love the Way You Lie” was written by Skylar Grey as an ode to the abusive relationship she had with the music industry.)

But the video isn’t about that. It’s actually a common refrain of complaints. On their own, each of them is factual. But let’s put them in context – most significantly, in the context of a pop industry that is partly collapsing, and partly re-aligning.

One at a time.

Lyrics are getting dumber. The loudest shouting involves pop lyrics getting dumber, based on a widely-shared study of “lyric intelligence.” I find these numbers utterly fascinating, if taken as a grain of salt. But apart from the sample size (a decade’s worth of Billboard chart toppers), we have to first consider the metric itself.

Almost everywhere I’ve seen the study quoted, it’s been presented in a profoundly misleading way. The data Seatsmart displays and compares is from the Flesch–Kincaid readability test, specifically the grade level score. You can do the same thing the Seatsmart writer did, by pasting stuff into a free website.

What the Flesch–Kincaid grade level actually does is weight text by density – density of syllables per word, and words per sentence. On some level, this could suggest something about the relative braininess of lyrics, but probably not in a terribly useful way. That is, Steven Sondheim will rank higher than Katy Perry, but – you knew that already. (“A wedding? What’s a wedding? It’s a prehistoric ritual where everybody promises fidelity forever which is maybe the most horri–” I’ll stop.)

But having greater syllable and word density doesn’t make something smarter, any more than food having more ingredients necessarily makes it better. Flesh-Kincaid has been criticized for being a poor study of actual readability even in its original context. It certainly was never intended to measure lyrics, which are sung and heard, since it was produced to measure text that’s read.

If you really want to defend the Seatsmart article, then congratulations, because you just became a fan of Nickleback and country music, who score highest in the story. CDM’s homepage currently scores only grade 4.5, which explains why we’re so damned popular with pre-teens. I won’t even start with the body of Classical music that repeats “Ave Maria” over and over again.

Or consider Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham, which scores an impossibly low -1.3 thanks to its nearly exclusive use of one-syllable words. Sure, it’s a kids book, technically – but as poetry, the person able to write like that has to be pretty darned smart. And that’s the whole point.

You’re certainly welcome to argue that pop lyrics are dumb or even dumber. But using the measure the US military used in the 1970s to grade the difficulty of their technical manuals – sorry, that’s just stupid.

Finally, as my last piece of evidence, I point you to the 1963 classic “Surfin’ Bird (Bird Is The Word)” as my choice of dumbest song lyrics (hilariously) of all time. Surfin’ Bird squeaks out grade level 2.6 on the F-K index, thanks to repeating the word “bird” in each line so many times and fleeting multi-syllabic action from the words “surfin'” and “everybody.” Try all you might, 21st century music industry, I think you’ll never get dumber. (Wait, now maybe I have argued that pop music has gotten worse, if 1963 was its peak.)

The talent you see aren’t the producers / writers aren’t producing. I’ll call this the “let’s pick on Taylor Swift again” measure.

On its surface, it’s true – many hit pop songs have separate credits for producer and writer. And indeed, the article quoted in the video is a fascinating read:

Hit Charade:

Meet the bald Norwegians and other unknowns who actually create the songs that top the charts [The Atlantic]

Since these writers dominate the charts, it is fair to say those charts are becoming less diverse. And it means that the talent you see aren’t necessarily writing their own songs.

What’s puzzling to me is the idea that this is a new phenomenon. Burt Bacharach has some 73 US and 52 UK Top 40 hits. Some composers have more hits than others. (Before Bacharach, there was Bach.) In fact, the real point here is that the writers are unknown.

And let’s come back to Taylor Swift, treated with derision in this video in this very example. I’m no Taylor Swift fanboy, but whether I like her songs or not does not entitle me to my own set of facts. And in fact what Taylor Swift has contributed to her records appears to be a significant amount of writing. Rather than random YouTube video contributors, you can ask someone like Imogen Heap – who effuses that Swift is in fact a significant creative force in her top hits. Imogen Heap is herself an example that artists can and do choose to write and produce their own music. (Imogen even does her own mixing, and she has two Grammy nominations and a win.)

Also, while Swift’s 1989 isn’t really my taste, songwriting and production are in fact different qualities. I recently had a thoroughly enjoyable listen to a set of Ryan Adams covers of that album, because the unplugged renditions let the songwriting come through differently.

Listen to the one track that Taylor herself wrote solo. I suppose it backs up the argument that pop production values can drown a track – no argument there. But it undermines the idea that Taylor can’t write. It’s an achingly beautiful song. It’s unmistakably a pop ballad, but sometimes those can be lovely.

Pop is getting more homogenous and louder and worse. Now, here, there may be a case to be made. The video above refers to a 2012 Spanish study that found in a larger dataset evidence that both timbral and harmonic complexity and diversity had weakened from 1955 to 2010.

Also, I think few producers would argue that the “loudness wars” have been damaging to music by over-compressing dynamic range, which by definition will remove dynamic contrast. Simply put, over-simplifying music’s dynamic range is subtracting information from a recording. The simple truth is, humans like things to sound louder – even those of us with sophisticated ears. But a good mastering engineer strikes a careful balance between overall loudness and dynamic information, one missing in a lot of top-of-the-charts pop music.

Remember that we’ve been talking about the loudness wars for a long time. Their rise came with the rise of corporate-owned terrestrial radio. I’m optimistic that we live in an age when young producers can get their hands on superb digital compression software and learn to master tracks properly (and work with capable mastering engineers).

But is music getting worse?

Here’s the crux of the problem. Many of the trends identified in the video are totally fair – and many are widely annoying.

But some of the trends missing from this (and many other) arguments are also important.

Pop music production is becoming more international. Whereas pop was traditionally dominated by decision makers in the US and UK, the future points elsewhere – South Korea’s Gangnam Style suggesting the tip of the iceberg as far as breakout hits from elsewhere in the world.

Traditional pop is threatened. There’s an unspoken implication in rants like the one above: pop music is getting worse, and the unwashed, stupid masses are lapping it up. The problem is, pop music is not the top-selling genre in the major US market (rock and country beat it by far, depending on how you divide up rock), and sales trends are all over the place. Pop sales went up in 2014, but the overall trend (like the rest of the industry) is down.

One way to interpret the dumbing down of pop music is as a survival mechanism, as sales come under greater pressure.

Artists are making their own choices. Whatever algorithm-driven, brickwall-compressed tunes are sitting at the top of the charts, that may say little about the trends across music making in general.

It makes sense that songs vying for big sales and chart-topping hits are composed and engineered in ways that makes them work on what’s left of broadcast media. If you landed from another planet and wanted to make it big there, it would make sense you’d go for very generic and very loud and put an attractive person as your celebrity.

Other channels, though, tell a different story. If you’re trying to make it on YouTube and social media, you better have a good gimmick. (See OK GO.) If you’re trying to make it live, finding a unique niche matters – and that’s a bigger driver as music sales dry up.

I think the bigger trend to watch than what makes pop work is what makes licensed music work. Look for artists to embrace quirky timbres, more dynamic range, and cinematic qualities as they vie for licensing on film, TV, video games, and the like. These all represent opposite musical directions from the ones the video above chooses to target.

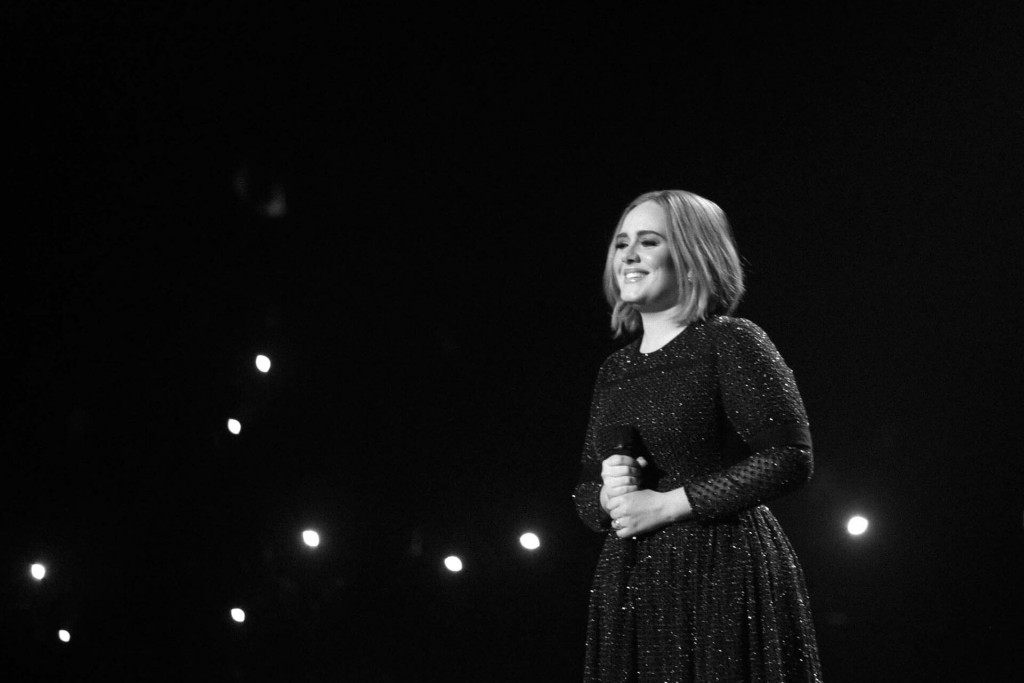

The new winners in pop look different. This video leaves out the one big champion of pop sales recently – with good reason, because she flies in the face of the whole argument.

Adele is the new face of success, co-writing her own music and getting sweeping accolades at an astounding rate – count nine Grammies and an Oscar (while juggling mothering a baby boy) by the age of 24.

She’s not old news, either. In fact, as of yesterday, ’25’ continued to top the charts, having been the best-selling album of 2015. Is her music too dumb, or too loud, or part of some secretive Norwegian conspiracy? I don’t think so.

It is collaborative, but pop music has always been collaborative. The Beatles were not a solo act. But they’re white English guys, so unlike female artists, they aren’t accused of any shenanigans even though George Martin defined their sound.

Music production itself is poised to become more diverse. To argue the history of the music industry is a meritocracy – the “better in the old days” argument – is supremely questionable. This is an industry with a long and ugly history of payola and racism, pay-for-play and segregated charts. It’s also an industry that was long dominated by the United States and the UK.

There is a darker side to a lot of this. Count the number of times “pop music is destroying the world” rants point to female artists or people of color, while using older white guys as the “grand old days” examples, and then decide whether you want some of these people on your side – even with some legitimate gripes about awful pop songs you would rightfully like to avoid. In the video above, in fact, one slide derides Beyoncé’s “Run the World” versus Bohemian Rhapsody. Now, what do you suppose would bother the video’s producer about Beyoncé’s lyrics?

In the USA, certainly, the fact that Rihanna is the most marketable celebrity suggests that the biggest shift isn’t in musical content, but a shift from white men to women of color that would before have been all but impossible. (And that’s to say nothing of the invading Koreans, or whomever turns out to be next.) That’s relevant in the context of this week’s criticism of the Oscars in Hollywood; the US formerly could market Elvis and the Beatles to an extent a differing extent than contemporary African-American artists.

Ranting about music you hate – that remains totally legitimate. But then the challenge should be to make sure that new people get opportunities.

Pop music on its own is not drowning out originality. But just as getting stuck on commercial success absolutely can destroy originality, so can getting stuck in the past. If anything, the Internet is proving that finding and promoting originality is a challenge. Rather than rant about what’s at the top of the charts, we should champion what’s failing to chart at all.

And don’t worry about how many chord changes or syllables you’ve got. Just turn off that brickwall limiter, please.