The blank screen. The half-finished project. The project that wants to be done.

We talk a lot about machines and plug-ins, dials and patch cords, tools and techniques. But the reality is, the most essential moments of the process go beyond that. They’re the moments when we switch on that central technology of our brain and creativity. And, very often, they crash and require a restart.

So it’s about time to start talking about the process of how we make music – even more so when that process is in some sense inseparable from the technology we use, whether the time-tested “technology” of music tradition or the latest Max for Live patch we’ve attempted to make work in a track.

Making Music is a book published, improbably, by Ableton. Sold out in its first paper run, with digital shortly on the way, it has already proven that there’s a hunger for creative tomes that harmonize with our tech-enabled world. Making the book Making Music is a story unto itself. Ableton’s Dennis DeSantis joins CDM to explain his own experience – and what happens when he gets stuck like the rest of us.

Do you still get stuck creatively sometimes? When? Did writing this help you find any new routes out of that?

I definitely do, and I also did while writing this book, which felt very meta. At this point, though, I’ve spent so much time thinking about the causes and solutions of my creative blocks that I can almost always blame pure procrastination or laziness if I’m stuck now. If I’m not getting work done, it’s probably because I’d simply rather be doing something else. Unless I’m faced with a deadline, I’ll usually just go do the other thing for a while.

I don’t think I uncovered anything new about my own process while writing this book. For the most part, it’s just a catalog of the kinds of things I think about anyway when making music. But I do think that the act of actually putting them down on paper forced me to think about them in a more streamlined, focused way.

You come, as I do, from a training in music composition and theory. To me, a lot of that clearly informs what you’re doing here. Where did that classical training inform what’s here? Is there a translation process for people who didn’t come from that technique and language – but who might benefit from the ideas?

The most obvious place is in the chapters that are heavily devoted to music theory. I mostly just thought about stripping away everything except the absolute most essential components. When I learned harmony it was via things like four-part chorale exercises, which I think is completely unnecessary for the way electronic musicians are working today, and probably unnecessary for learning how harmony works in general. In the context of the traditional conservatory model of harmony instruction, the chapters in my book probably look too stripped down. But I’ve heard from a number of early readers that they finally “get” the concept of functional harmony for the first time, and I’d like to think this validates my approach.

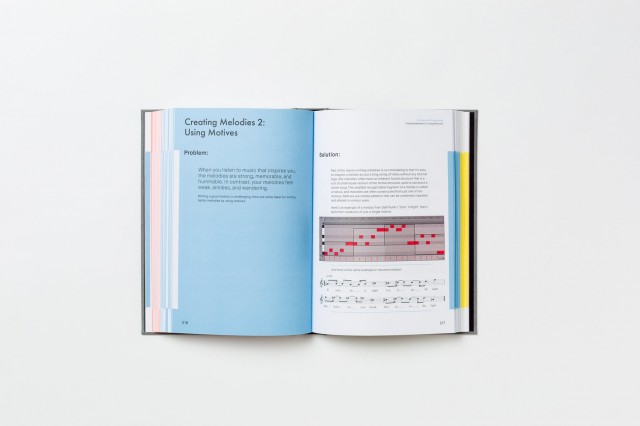

Besides the theory-heavy chapters, there are a number of more abstract concepts I learned from traditional composition training, about topics like motivic development, creating variations to expand a small amount of material into something larger, etc. These ideas are general purpose enough that I think they can be presented to people who are outside of the world of classical training, and without all of the baggage that comes from also having to learn 800 years of music to be able to cite relevant examples. It’s not actually necessary to study Mozart string quartets to figure out how good melodic writing works; you can find it in Daft Punk tracks.

You say you’ve now gone from classical music to house and techno. Why that transition, what’s new about working in those idioms versus classical work – and would you say the tech has played a role in that shift for you?

Well, I don’t think it’s an open door/shut door kind of situation. I haven’t turned my back on anything, and I’m always open to writing more concert music if the project feels right. But in general, I found that I was just way more interested in what was happening in electronic music, both at a musical level and at a cultural one. I gradually started to have more and more experiences with concert music where I felt like the little kid in the story “The Emperor’s New Clothes”—and this was even true when listening to my own concert music, which, with a few exceptions, is mostly not very good.

I don’t think tech played a role for me as much as my realization that I wasn’t particularly interested in the interpretation layer that’s implicit in any composer/performer relationship. When you’re writing for instruments played by other people, you’re subject to their own physical and artistic wishes and limitations. You provide notated music that conveys an extremely limited amount of information and what you get back is one possible performance, filtered through those people and their instruments. In very special cases, you get back something that’s better than what you imagined. But the rest of the time, you don’t

On the other hand, I can get exactly what I want when writing music for machines. If I want to tweak a kick drum sound for nine hours, I can do that without making someone else suffer. There’s no need for me to compromise anything, ever. For me, this is a much more appealing way to spend creative time. Right now, I’m just fundamentally much more interested in the kinds of musical things machines can do than the kinds of musical things people can do. That’s not to say I don’t like to hear a great band play great music sometimes. But I’m not so interested in them playing my music.

People may be surprised that Ableton Live really isn’t ever explicitly mentioned in the book, to the point of avoiding it. But then it’s there in the images. What was Live’s role in this book?

Live is the DAW I use for my own work, so it’s naturally what I gravitated to for the screenshots. The ideas really are meant to be equipment-agnostic, although I’ve been using Live for so long that it’s hard for me to have an outsider’s sense of how much its inherent workflows have influenced the way I think about music now. I do think anyone making music with machines can get something out of this book, whether they use Live or not.

Your examples here seem to oscillate between larger theoretical ideas and, sometimes, very specific practical ideas. Sometimes they’re recipes, sometimes broader concepts. How did you approach that? How did you organize these different levels? (Oblique Strategies appears to be an influence in some ways… Fux? Rameau? Cage?)

It’s pretty unorganized, actually, or at least it was while writing. I tried to sort and order things by general concept only after finishing writing. What I did figure out fairly early on was that I wanted to segment things into the three big phases of actual work: beginning, progressing, and finishing. I think these phases have their own unique sets of problems and solutions, and it felt like they should be separated. Beyond that, things are loosely grouped based on their discussion of broad musical concepts like melody, harmony, rhythm, and form.

Oblique Strategies, of course, looms large over any project like this. But what I really wanted to do was something not at all oblique. I wanted simple, concrete problems with simple, concrete solutions; direct strategies.

It’s funny, two of the people I know who have been really good at speaking to electronic musical practice and do that for Ableton have been you and Dave Hill, Jr. (Dave’s now at iZotope) – and you’re both percussionists. Does that experience playing rhythm physically inform what you do?

For me, I guess it does, and many of the chapters are specifically about drumming concepts. One of the things I like to do in my own music is to play little rhythmic games—uneven loops, un-synced automation gestures, polyrhythms, etc. These aren’t concepts that are inherently “about” drumming, but I guess drummers tend to think about patterns and pattern relationships more than some other musicians.

I can’t speak for Dave, although certainly some of his ability to speak eloquently comes from him being a genuinely smart, thoughtful guy. He’s also a great drummer, although I have no idea how much this plays into his thinking about electronic music. I should ask him, because it’s an interesting question.

Some of these challenges are to do with theory and musicianship, some with expressing ideas with the technology. Is there a distinction between those, areas where they pull apart? Do they all blur?

At this point, it all blurs for me, although my overarching goal with this book was to write something that was decidedly not about technology. I wrote the book to address what I see as a huge imbalance between the amount of good resources available on the music side versus the technology side. There are so many tutorials about how to use tools, and so few about how to make music with them. This book is an attempt to remedy that, and I hope there will be more like it. I know there are people out there who can tackle this topic from different perspectives, and I’d love to read what they have to say.

Your day job, as it were, is support at Ableton. Tell us a little bit about what you do. And what’s your day like?

Not really support, but rather documentation. I’m not actually on the phones with customers. I write the manual and other tutorials for Live and Push, as well as helping out with some marketing writing. Sometimes I help on the product design side as well.

How did you find the time to make music while writing this book and working at Ableton?

Honestly, I barely did, which I guess calls into question whether I’m qualified to be writing a book like this at all! I did only a little bit of music in 2014. But now that the book is out, I hope to find more time for it this year.

Hope you do, too, Dennis – I want to hear it, apart from Ableton! Thanks! Check out the book here – and follow CDM on Facebook for news of when the digital edition becomes available.

https://makingmusic.ableton.com/