Sony’s Walkman turned 40 earlier this month. But look to the TC-50 before it for some of the technology and usability innovations that changed the world – and joined the Apollo mission – plus a glimpse of where music might boldly go next.

Sony’s story will sound familiar to a lot of today’s sound DIYers, synth makers, and Eurorack inventors. The operation began with a cheap disused space and a few people learning on the job by repairing electronics. The company might be known for transforming cassettes, but earlier projects involved a rice cooker and an electric cushion.

But long before Apple, it was Sony that introduced the world – and especially the lucrative American market – to the idea of miniaturized portable electronics. That included the TR series transistor radio. (Oh, note the other similarity – yes, it’s a safe bet that Roland’s Western-friendly brand name and XX-NNN product names are inspired by the likes of Sony and Sanyo.)

And that brings us to the TC series cassette recorders. There’s really a lot in these devices that predicts not only the Walkman, but devices like the iPhone, as well. As with transistor radios, miniaturized electronics enable a design that becomes personal and portable, which changes the whole relationship of user to device.

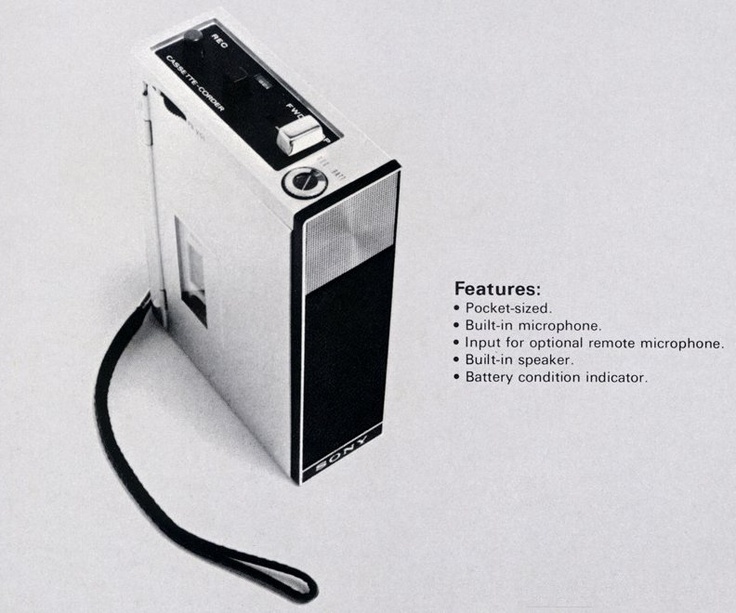

The 1968 TC-50 looks elegant and modern even by today’s standards. It combines a number of key innovations that make that possible – not necessarily invented by Sony or by the TC-50, but combined in a single product in a way that transforms that technology into user experience:

Integrated circuits. ICs are what has brought us the entire consumer electronics – and musical electronics – revolution. The chip replaces whole circuits of separate components. On the TC-50, that lets the design revolve around the user’s hand, the controls, the mic, and the cassette – everything else more or less disappears. Sony began in the 50s designing its own components, thanks to tech it had licensed from Bell.

Compact component mounting. This is actually equally as big a deal – each component’s mounts are also reduced, which further miniaturizes the design.

Built-in microphone. This is the innovation that’s the reason the TC-50 went into space – and while we take it for granted now, it’s what cleared a pathway for the likes of the iPhone. Sony’s custom mic design is small, integrated with the device, but still records high-quality audio. When NASA equipped its astronauts with the TC-50, it was for personal memo recording, not mix tapes (though more on the latter in a moment). That personal functionality also establishes the handheld device as a portable companion. If that seems a stretch when talking about the iPhone (even with “phone” in the title), I might also observe that Apple has told me its Voice Memos app is one of its most popular.

One-handed, wireless operation. Here’s the other big innovation that brings it all together. The entire design – placement and operation of buttons, form factor – is built to enable one-handed operation. Just as with so many accessibility innovations, that in turn yields unexpected advantages. In the case of the TC-50, it meant astronauts could record audio while wearing their bulky spacesuit gloves, starting with Apollo 7 and most famously on the Apollo 11 moon voyage. That kind of usability thinking would go on to inspire companies like Apple, and it’s always worth revisiting. (When I worked on WretchUp with Mouse on Mars, I did a lot of adjustment work with Andi to design gestural controls that you could use with a single hand, and even without looking closely at the device, for onstage use.)

Natural industrial design, focused on materials. You can almost hear Jony Ive marveling at the luxurious, exposed “aluminium” – and yes, years before he met Ive, Steve Jobs also saw Sony as a personal design inspiration (alongside Braun and Mercedes-Benz). The TC-50 came too soon to benefit from the 21st Century’s economy of scale, so you can bet the “luxury” of that aluminum surface had a price tag attached. But Sony excelled at modern adoption of these material processes, which had allowed it to work with companies like watchmaker Bulova back to the TR-55 transistor radio. And so it is that today’s smartphones also telegraph their use of strong materials. See also this excellent story on the 1972 TC-55, which starts to look more like a Walkman, and moves public perception from “cheap plastic” to “fine metal.”

Apollo and the TC-50

NASA astronauts definitely used portable cassette recorders, the Sony TC-50 being one. They also made famous use of a modified Hasselblad 70mm film camera, including on the lunar landing during Apollo 11 (see National Air and Space Museum).

I found some differing accounts of which missions the recorder was aboard. Sony themselves note the TC-50 debuted on Apollo 7, the mission that was the first Apollo to carry a crew (and the first human spaceflight mission after the conclusion of Gemini and the tragic Apollo 1 launchpad fire). The TC-50 also got pretty close to the moon on Apollo 10, the key mission that simulated the lunar descent.

From the accounts I’ve read, it sounds as though there was a TC-50 on Apollo 11, but it probably didn’t go “to the moon” in that it seems it stayed aboard the Apollo Command Module, not the Lunar Module that made the trip to the moon’s surface. And Buzz Aldrin did request a mix of music for the trip, dubbed to the compact cassette format of the TC-50.

Vanity Fair learned the details of the Apollo 11 mixtape from record exec Mickey Kapp in an interview late last year:

Music on the Moon: Meet Mickey Kapp, Master of Apollo 11’s Astro-Mixtapes

They made the essential playlist for Spotify, natch:

One Aldrin favorite, now featured in the upcoming documentary on the mission, is this poignant – and self-critical, self-aware, hardly jingoistic – John Stewart release:

There’s nothing particularly cosmic in the mix; the choices are sentimental, personal. When they go to the lunar theme, they’re lush and romantic as much as trippy. And they’re singular; this isn’t background music. I think that says something about our connection to music, something that generative tunes or machine learning are unlikely ever to replace – they’re still, you know, songs.

The mix for Buzz was made in a living room, reports VF, complete with mistakes. That’s something that’s been unquestionably lost, and even at the time must have stood in contrast to the mission-critical clockwork of a space mission.

I wonder, though, if the TC-50 doesn’t point us to a fresh perspective on music. Right now, so much of our thinking about how music should be shared is stuck in the past. Whether lamenting the loss of tangible media and record stores, or defending them by stalwartly DJing with “vinyl only” sets, the whole conversation is framed by what was.

The TC-50, apart from having been aboard humankind’s most audacious mission yet out of our planet’s orbit, isn’t bound by any of that past. It’s informed by watchmaking-quality metals and the iteration of electronics. But it’s designed anew around the best quality of each of those disciplines. It looks familiar and inevitable to us only because we are the children of the age it shaped.

That is to say, maybe the first and most reasonable answer to the question of “what should music listening look like in the future” might well be I don’t know. The people at Sony didn’t know right away. They cut their teeth on rice cookers in the wreckage of a ruined empire, dug deep into the latest advances from Bell in the USA, and spent incalculable hours just disassembling someone else’s electronics, and putting them back together so they worked again. Sony’s first introduction to the cassette was hitting on a technology that improved on primitive wire recorders they’d seen in military use. Apollo for its part was built on iterations from missiles and ran on computers whose memory was woven together, literally, by textile workers.

We live in an era that values fast answers and quick financial returns, but the very breakthroughs that make those people so rich weren’t brainstormed in a coworking center on a whiteboard by someone microdosing LSD. They were crafted over years through hands-on, sweat and tears work on physical materials and engineering.

Maybe we don’t need new devices or new physical media for sound – that’s possible. We’ll certainly need devices to record sound and to play music; anything that must be touched can’t simply be streamed.

I suspect, too, that we may see new devices for listening, built around new developments in immersive sound.

I also think it’s telling that the TC-50 was a recording and creation device as well as listening device, and that those functions were ultimately linked. The smartphone fits that mold, of course – but other as-yet-undreamt-of devices could go there, as well, in ways the smartphone can’t.

So why not return to some of that day-in, day-out engineering and craft to find the next big thing?

Some of the TC-50s still work, too:

Image at top – Dave Scott peeks out of the Apollo 10 Command Module, in this photo shot by Rusty Schweickart as the Lunar Module was docked, in a “dress rehearsal” of Apollo 11. Photo: NASA.

PS – I have no idea what kind of audio or film equipment was used aboard Soviet missions of this period, so maybe my Russian friends or space buffs can answer that.