Defining and re-imagining performance with computers and technology is an ongoing theme of this site. In a special guest column, artist Primus Luta goes deeper into that question with some of our favorite artists to look at practical and philosophical dimensions of playing electronics.

Today, the fruits of electronic musical labor can be heard in every corner of culture, from academic to niche to popular. Still, there remains a perceptual disconnect between traditional and electronic music, especially in the context of performance. With traditional instruments, performance proficiency can be measured as a physical accomplishment. Electronic performance, on the other hand, is generally understood as music made by computers. That poses a question: if the music is being made by the machines, what exactly does the musician do? To find out, I talked with some of the best electronic performers on the road, and got a glimpse of what exactly is going on behind the screen.

Live Rig: Mark de Clive-Lowe

From the Studio to the Stage

Historically, performance long preceded recorded music. Early recordings weren’t what we think of today as studio productions, but rather recordings of performances. Electronic music is a bit of an anomaly. While some early electronic compositions were created for live performance, most electronic music today begins with a recording.

Translating the high production values heard on a record into a live performance isn’t an easy task. It isn’t always possible to recreate the same aesthetic on stage, but it is important to make the connection.

“We can multi-track sounds in the studio,” explains 8 Bit Weapon, “but live, you are stuck with all the limitations the vintage computers, consoles and sound chips have to offer. So we have to trim down parts or add parts that are recorded by recreating them live.”

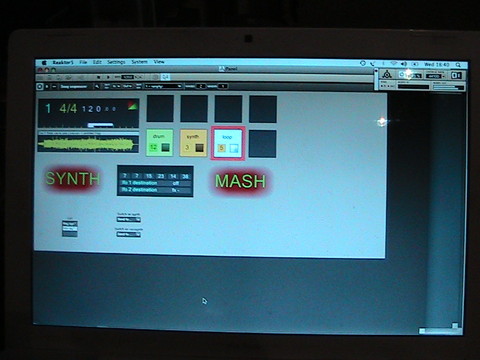

For Richard Devine, assembling the live performance begins in the studio with “trying to translate all the programmed MIDI data and song transitions into Ableton [Live]. Ableton is running the pieces of my tracks. I have hundreds of audio clips running in session view.” Onstage, this allows Devine to “mix and match breaks, intros, or builds for different tracks, and even manipulate how those are played if I select them. I can really do anything with the arrangement of the original track. It is now total remixing and producing on the fly.”

What this means for electronic performance is the ability to condense what could be days of production work into a performance piece of a few minutes. “It’s really similar to my studio process, on fast-forward!” says Mark de Clive-Lowe.

“We create tracks in the studio in the normal fashion,” says J Tonal of The Flying Skulls. “They get broken up in to drum and bass parts, which get played live on the MPC, melody and lead parts which get played on the MS2000, and samples and other melody parts which get broken down into [Ableton] Live clips and played from [an M-Audio] Trigger Finger.” These pieces are then used live to create what they call deconstruxions.

As Mark de Clive-Lowe explains, “the idea of reinterpreting and translating the same pieces to different audiences with different bands and setups is nothing new.” In other words, rearranging electronic music for performance contexts does have its roots in a larger musical tradition.

For some, this has resulted in working to restore the historical role of performance as the heart of a recording. “The experience of participating in a musical happening is ephemeral and never translates to a record,” says Tim Exile. “I have developed a number of paths of improvisation which you could consider scores… these are adaptive positive feedback responses to features of the musical environments I’ve been in. These features can be very local, such as the slight manufacturing error in one of the buttons on the control surfaces causing it to be slightly harder to hit to be sure of pressing it, to the very wide, such as the proliferation of a new genre changing the way audiences categorize and respond to certain musical structures.”

This interplay of the studio and performance feeds the creative loop to take a new shape each time the artist goes on stage. “Most of my studio output is mellow,” says Daedelus. “Most performances are riotous or at least dance-able. So finding relationships and movement in my own output is quite fun, and leads to disaster in the best nights.”

Is It Live Or Memorex?

When it comes to electronic music performance, is the music is being performed or played? As technology like Ableton Live evolves, the line between the two may blur to the point of irrelevance. As Tim Exile explains, “the discussion lies more in the boundaries between performance of compositions and improvisation. Most of what I see being played live these days seems of the live arrangement variation, focusing mostly on compression or expansion of set arrangements in response to the environment. This is live and adaptive and of the same genus as the style of performance exercised in DJing.”

Whatever the prepared sources, this adaptive style is undeniably a performance. “I can’t always reproduce the same exact show twice now,” says Richard Devine. “There are now so many different variables that can change or be manipulated.”

“I employ a lot of pre-made loops,” says Daedlus. “In some regards the legos are in a large box and I try to make spaceships or castles accordingly.”

“There are a lot of our songs that have a prerecorded studio version,” says J Tonal. “That gets played for about two minutes, and then we switch it up into a deconstruction and play a live remixed version of the same song.” Over top of backing tracks from their songs, Seth and Michelle of 8 Bit Weapon “play the Commodore 64 and 128 live like pianos, and use the Apple IIc as a mono synth in the same fashion. The Game Boy can do very basic live sounds and sequences.”

The Nucleus

At the center of any musical performance is the instrument. For electronic music, that instrument is the live rig. That rig can be a single laptop or an intricate hybrid of hardware and software; the possible configurations are limitless. Combining controllers, sound sources, mixing, and effects determines the breadth of available sound. The shape the rig takes becomes the defining point for the artist.

No matter how large, most rigs contain a center – a nucleus from which the soundscape is derived. For Daedelus that nucleus is the monome. “My preoccupation is with the Monome,” he explains, “especially MLR and added goodies tailored for use. I find it the most freeing from linear shackles, figuartive handcuffs, and my own preconceptions. It is improvisatory in the same way jamming in a jazz ensamble is, but with samples.”

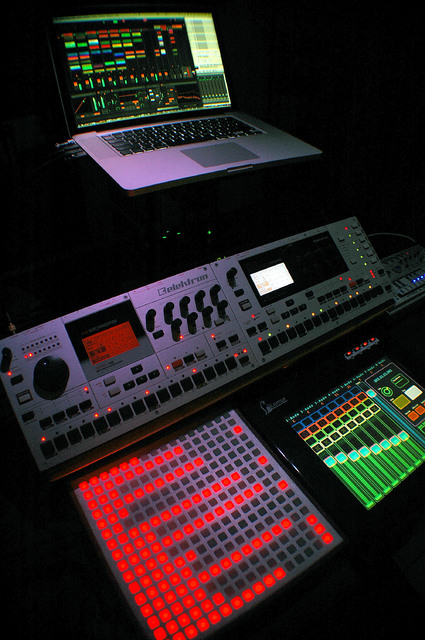

Even if your rig is multi-faceted, the improvisational aspect is essential. As Richard Devine explains, his hybrid rig provides “maximum flexibility to change anything at any point in my show.” At the center is a MacBook Pro running Ableton Live 8 which syncs his three primary controllers. “The Monome is dedicated to doing random FM synth triggering with Max, and the MonoMachine is doing lots of synth and baselines, while the Machine Drum handles the huge analogue kick drums, and skeletal backbone percussion.”

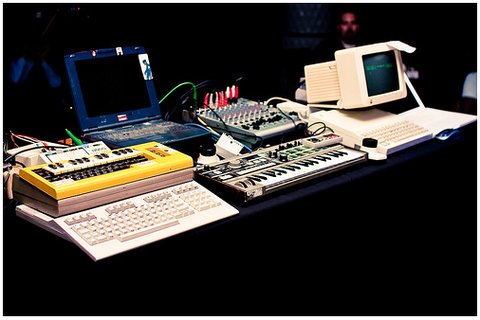

Equally complex is the hybrid rig of 8 Bit Weapon. There’s still a laptop, but along with it they have “a Commodore 64 computer, a Commodore 128 computer, a Game Boy, a Apple IIc computer, Elektron Sid Station [containing a C64 sound chip], Nintendo Entertainment System, KORG microKORG vocoder, and a 12-channel mixer.”

While a laptop does all of the number crunching for Tim Exile, the true center of his rig is his two Behringer BCR2000’s and one BCF2000. “The 2-way control is perfectly implemented, and there are hacks around that allow you to use every single button on the surface. I’ve made my own context-sensitive control for layer switching in Reaktor. Pretty much all the state info I need is right there on the controllers.”

Mark de Clive-Lowe’s rig may look like that of a keyboardist with a Rhodes, Clavinet, and other synths. But what he calls “the heart of the show” is the MPC3000 he uses to program beats live. “The tactile interface means i can really get into playing the drum machine like an instrument.”

For The Flying Skulls, each performer takes different instrumental roles. Bringing those instruments together is the Rane Empath. “It operates like a master mixing console for several elements of the show: Snareface on the MPC, Jerome on the MS2000, and a channel from Live running on J Tonal’s laptop.” Using the Empath’s Flex-FX, they “get real-time access to over 100 effects that can be applied to any or all of the channels with touch-sensitive parameter control.”

Audience: Engaged

There is always the need to engage the audience. “This is crucial,” says Richard Devine. “You have to somehow connect with them. I usually try to play some songs that people know, and of course try to play out lots of new material that hasn’t been heard. I like to program large builds and breaks to take the audience on a roller coaster ride, if you will.”

Leading the audience through the performance is no easy task with all the variables in a complex rig, but getting the audience to link the performance to what they are hearing aurally is its own reward.

“Movement is as important as sound in this respect,” says Tim Exile. “I’ve noticed that audiences respond well when they make connections between movements and sounds which they’ve never made before. So if they can see you directly controlling a sound structure which they’d only heard devoid from its kinetic correlate before (a lot of electronic sounds) then they will have a transformative experience.”

“They are seeing a full studio production created at break-neck speed live on stage in front of them,” says Mark de Cliv-Lowe. “They go on a journey via the music – the rhythm, the harmony and the melody.”

Artists can adapt the journey by feeding off the audience. “They are the ocean currents,” says Daedelus muses. “Fighting directly against [them] is useless. I mean, you can tack the ship against the prevailing winds, but you don’t get very far. I like having a direction, but watching and listening and being willing to go elsewhere.”

This doesn’t eliminate the value of more traditional ways of audience engagement. “Definitely always have a mic to talk to yer crowd,” advises J Tonal. “We like to make sure the audience is on the same page as us,” 8 Bit Weapon shares. “We check in from time to time between songs using fun banter.” There is always room in any musical performance for fun banter, but Daedelus warns, “never let audience members try to speak to you in drug-addled states during performance. It is a careless whisper, no Wham reference.”

There Will Be FAIL

With all of the amazing things we’ve been able to do with technology, we’ve yet to perfect the anti-fail science. If only repairing a crashed hard drive were as simple as changing a guitar string.

“I’ve had MPC’s blow up and melt down right before and during gigs,” recalls Mark de Clive-Lowe. “I have played many shows,” says Richard Devine, “where my computer had crashed right before I was to play or I had some hardware sync problems.”

“We have sent the Sidstation back to Sweden for repairs 2 or 3 times,” 8 Bit Weapon recalls. “A drunk club patron tore it right off the stage and it slammed on the floor.”

Managing these inevitable situations is as much a part of the performance as anything else. “The biggest skill for a live performer,” Mark de Clive-Lowe says, “is to be able to take a mistake and flip it so it was never a mistake.” “When you have only a short amount of time to play — when something goes wrong, you have to have a back up plan, which may be having another computer ready to go on standby or another piece of hardware that you can use to play,” says Richard Devine. “There is nothing worse then flying around the world to play a show and running into technical problems.”

But perhaps the absolute worst scenario is, as Tim Exile says, “not being in the right mood. There’s very little you can do about that. There are no other mistakes.”

Primus Luta is a musician, technologist and a writer. When not working to finish his Heads Project, he’s trying to convince himself he’s got it in him to write that book he always wanted to write.

Primus Luta’s blog on noisepages, featuring computer music performance techniques, Plogue Bidule tips, and a lot more:

http://plpheads.createdigitalmusic.com/

See the companion video gallery for this story, featuring live performances from the artists interviewed. [about to be posted]