By the 1990s, the notion that computer software could be a means of delivering interactive digital art more personally was enjoying a Renaissance. This was the age of the Voyager CD-ROM, which catered to new multimedia PCs and Macs with titles from the likes of Laurie Anderson and Morton Subotnick, the decade in which Brian Eno released Generative Music as software and Monolake – before Ableton – included a Max/MSP patch with an album. But the reach of these experiments was doomed to be relatively limited.

Now, of course, things are different. First, we saw some widely-available audiovisual toys, coinciding in particular with the debut of the iTunes App Store. But now, those fairly one-dimensional experiments are beginning to blossom into something else. When these particular gadgets and app stores are forgotten, the question is whether those aesthetic adventures, the personalization of the digital art experience, will endure.

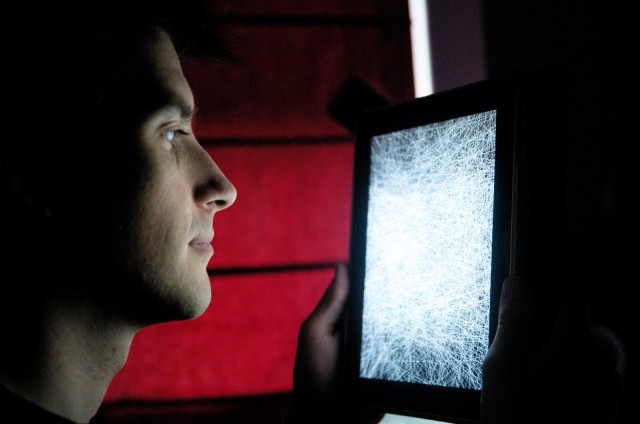

Joshue Ott, co-creator of Thicket for iOS, points to a review of that application on Apple’s App Store. “I always want to touch the masterpieces in museums,” a user says in that review. “I’ll use Thicket instead of getting arrested!”

“It’s the democratization of our own performance works,” muses Ott. “It’s a way people can play along with us,” he says. “We’re constantly creating processes to create sound and music; it’s what we’ve done for ten years or so,” chimes in Ott’s creative partner, Morgan Packard. “Now people can own the processes, not just the results.”

Ott and creative partner Packard have long each been visual and music performers, respectively. That meant what it has traditionally meant: the artist gets up in front of an audience, the real work hidden behind an onstage laptop. With Thicket, by contrast, the raw materials of that performance became embodied in the software itself, and thus in the hands of the audience, who can double as performer. At first, this software included only a simple mode or two, each with a specific sound, musical ambience, and visual look. Even in those versions, Thicket made some appearances in an occasional gallery show or performance – the app you download could also be the art.

As Thicket has added modes, though, it has evolved in a kind of platform of its own. Ott and Packard produce new works that can be distributed as in-app purchases (more on how they contend with that in a bit). The sum total of those modes has created a massive audiovisual playground, a compendium of ideas and aesthetic.

A new version released this week adds three new modes, seen in the video at top here, building atop modes added in late December. For the first time, you can use Thicket on an iPhone and not just an iPad; it’s a Universal app. Screenshot sharing is available, too. But the addition of all these modes, unveiled with a “reboot” of the app at the end of last year, represents a shift in thinking as these artists and developers reevaluated what it was they were doing.

“We found that the modes were becoming so different, so much deeper,” says Ott:

We were having such fun using it as a big sketchbook that we decided to ditch the ‘rotate to change modes’ system so that we could handle lots of modes, rather than just four or five. The modes in Thicket reboot are completely new, and each one is a lot more complex than the older modes. They’re all very different, and each have separate methodologies behind how you control them. We’re playing with different concepts in user interaction design, searching for the right intuitive feel to make a true audiovisual instrument (among quite a few other things).

In other words, if you haven’t played with Thicket lately, it’s a different animal. It’s a Long Play album to the first version’s single cut. The work is immersive, too; you can transmit video output via HDMI or VGA on the iPad, and get up to 1920×1200 HD output, with no menu intervening. (One of the many significant current drawbacks of Android for the moment for artists: the move to a soft menu on Android tablets means menu detritus that never goes away. Artists were intensely relieved this week when Apple’s new iPad kept its signature, dedicated hardware menu button.)

Morgan Packard says he has some strong feelings about why this kind of experience has value in his work:

I’d say where we both overlap is our shared interest in how abstract sound and picture, plus interactivity, all can work together. Thicket is a bit of a research sketchbook for us. There’s something very magical about just twiddling your fingers and having sound and visuals spring to life. Frankly, we don’t entirely understand this medium yet. But we like not knowing, trying to understand it in different ways.

The gestural thing is huge with us, and is at the core of what thicket is. It’s partly why I’m a bit resistant to the idea of layering features on to Thicket. Of all the different people who give us feedback, I get the most gratification from parents of special needs kids.The non-fiddly, large-motor interaction style is very accessible to a huge range of minds and hands. I want to explore this more, to give people new ways of feeling expressive and creative with movement and gesture. In my mind, that’s what’s really special about what we’re doing.

The duo did get a chance to try the app with people with different user needs. Ott explains:

Morgan and I actually toured a special needs school earlier this year and observed autistic kids using Thicket. A very special music teacher is using Thicket (among a couple of other technologies) to teach the kids music, and had found that it seemed to really empower them. He offered to let us visit and we happily agreed… really really amazing experience.

As Subotnick hoped years ago in “All My Hummingbirds Have Alibis” for Voyager, the distribution of art as software can create a new kind of “chamber” art, in which the work is personal, enjoyed by a few people. It can be a family or a couple of friends on a couch.

Of course, somewhere in all of this, these artists are looking for revenue in order to be able to devote the massive amounts of development and testing time the application demands. (Neither has quit day jobs, which means finding a way to devote resources to development.) Thicket easily climbed in download counts, but only after the application was made free. In-app purchases have been a tough mountain to climb, but have at least allowed some revenue to trickle in; the challenge was finding a way to make them appealing to users, says Ott:

I think in general people hate In-App Purchasing (IAP), because, in general, I think IAP is usually not handled so well. We have thought a lot about how to show people exactly what they are buying before they buy it, and I’m really pleased with what we’ve come up with. Every mode in the new Thicket has a pre-recorded “demo” of one of us playing the mode. Before you buy a mode you can watch this demo, learn what the mode can do, watch someone use it in an interesting way, and decide if that’s something you’re interested in or not. You can of course watch the demos even after you’ve purchased the mode (and the free Sinemorph mode also includes a demo as well). The demos are a great way for us to show users different tricks and techniques.

So the reboot is really about making Thicket a platform rather than just a single art piece. Something that we can keep adding to (with a financial structure that makes sense for us to keep adding to). Something that we can start collaborating with other artists on – we are talking to a couple of different people about releasing modes within the Thicket system. So yeah, that’s what the platform part is. We’re really excited about it, and what it will become in the future.

But these concerns aside, the developers aren’t just creating Thicket for users; they’re building something they use themselves. As Josh explains:

I’ve performed with Thicket now a couple of times, once at the excellent SONiC festival, and another at Issue Project Room in a program curated by Ryan Lott (AKA Son Lux), and have started to really feel like it has the potential to be a new form of audiovisual instrument. I want to see more stuff like it- things that generate graphics and audio intertwined, and I want to continue to explore these relationships in different ways. I’m actually pretty excited about performing with Thicket more, and I think doing so will push it even further in that direction.

“That’s really what an audiovisual instrument is to me,” says Ott. “It’s something that you can bang on and make something interesting, but you can touch it subtly, as well, to shape it, to express with it. That’s what I want to make. We’re right at the beginning of that exploration, and I think we have something that is a promising vehicle for it.”

You can try out the new Thicket now, as seen in CDM Apps:

Thicket @ CDM Apps

[Says iPad, is actually now Universal. PS – music and beauty flow from my fingers all the time – no app needed – but I’m glad now the rest of you get the chance.]