How do you visualize the invisible? How do expose a process with multiple parameters in a way that’s straightforward and musically intuitive? Can messing about with granular sound feel like touching that sound – something untouchable?

Music’s ephemeral, unseeable quality, and the ways we approach sound in computer music in similarly abstract ways, are part of the pleasure of making noise. But working out how to then design around that can be equally satisfying. That’s why it’s wonderful to see work like the upcoming Borderlands for iPad and desktop. It solves a problem familiar to computer users – designing an interface for a granular playback instrument – but does so in a way that’s uncommonly clear. And with free code and research sharing, it could help inspire other projects, too.

Its creator also reminds, us, though, that the impetus for all of this can be the quest for beautiful sound.

Creator Chris Carlson is publishing source code and a presentation for the NIME [New Interfaces for Musical Expression] conference. But this isn’t just an academic problem or a fun design exercise: he also uses this tool in performance, so the design is informed by those needs. (I’m especially attuned to this particular problem, as I was recently mucking about with a Pd patch of mine that did similar things, working out how to perform with it and what the interface should look like. I know I’m not alone, either.)

The basic function of the app: load up a selection of audio clips, and the software distributes them graphically in the interface. Next:

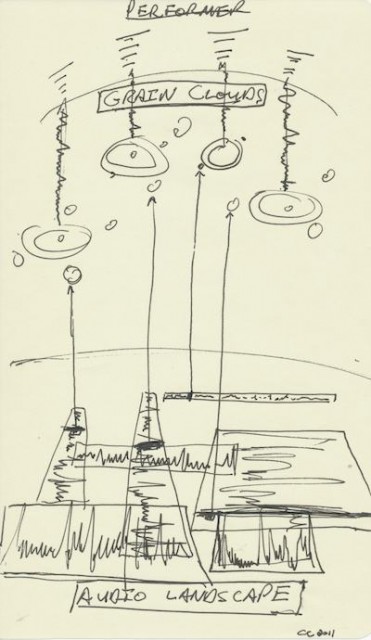

A “grain cloud” may be added to the screen under the current mouse position with the press of a key. This cloud has an internal timing system that triggers individual grain voices in sequence. The user has control over the number of grain voices in a cloud, the overlap of these grains, the duration, the pitch, the window/envelope, and the extent of random motion in the XY plane. By selecting a cloud and moving it over a rectangle, the sound contained in the rectangle will be sampled at the relative position of each grain voice as it is triggered. By moving the cloud in along the dimension of the rectangle that is orthogonal to the time dimension, the amplitude of the resulting grain bursts changes.

You can see how Chris is imagining this conceptually in a sketch he shares on his site:

An extended demo shows in greater detail how this all works:

Chris is a second-year Master’s student at Stanford University’s Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics [CCRMA] in California. The iPad version is coming soon, but you can get started with the Linux and Mac versions right away, and even join a SoundCloud group to share what you’re making. You’ll find all the details, and links to source code, on the CCRMA site. (And if someone feels like building this on Windows, you can save Chris the trouble.)

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~carlsonc/256a/Borderlands/index.html

I also love this Max Mathews quote Chris shares as inspiration:

Max Mathews, in a lecture delivered at Stanford in the fall of 2010

“Any sound that the human ear can hear can be made by a sequence of digits. And that’s a true theorem. Most of the sounds that you make, shall we say randomly are either uninteresting, or horrible, or downright dangerous to your hearing. There’s an awful lot to be learned on how to make sounds that are beautiful.”

Beyond the technology, beyond this design I admire, anything that sends you on the path to making beautiful sound seems to be a worthy exercise. It’s a challenge you can face every day and never grow tired.

http://modulationindex.com/ [Chris’ site, with more information]

Thanks to Ingmar Koch (Dr. Walker) for the tip!