As the transformation of music heats up, the discussions are heating up, too.

Case in point: yesterday’s report on Eternify certainly earned some angry responses.

I was of the opinion that Eternify was a decent gimmick – a way of showing just how small fees from streamed music are. Imagine if the music you bought only got a fraction of a cent to the artist each time you played it. I don’t think there’s practically an album in my collection I’ve listened to enough times that streaming fees would add up to purchase fees.

Now, does that mean that Spotify or Apple Music are the end of music? Not necessarily. It’s clear that the industry built around record labels hasn’t always served artists well. (Cough. Understatement.) Streaming services offer more questions. What sort of access will artists have to getting their music on these services directly – even bypassing a label? What sort of control will they have once it’s there? How can they help people find their music, and what sort of data about listeners can they collect?

In other words, we’re entering a more multi-dimensional industry. Instead of focusing on the actual purchase price of a recording, or even a per-play license fee in the conventional collections model, the game now is really about what the total value of a service is to artists.

Remember that I noted that not only was the lion’s share of streaming revenue going to labels, but it seemed those same labels were blowing most of that income on marketing. It’s not just a question of how much revenue music earns. It’s a question of how much you have to pay to get that revenue in the first place – expenses versus income being business 101.

But to anyone who said that Eternify was cheating – you’re absolutely right. (I thought it was sort of obvious that you couldn’t effectively use this to make cash, but maybe not.) I was politely informed my multiple sources that at best, it wouldn’t earn anyone any money, and at worst, it could get music or users banned. And sure enough, it was promptly shut down.

That brings us back to what Spotify actually can do.

One of the weirder applications showed up in my inbox today. Get ready for CDM – Create Dating Music.

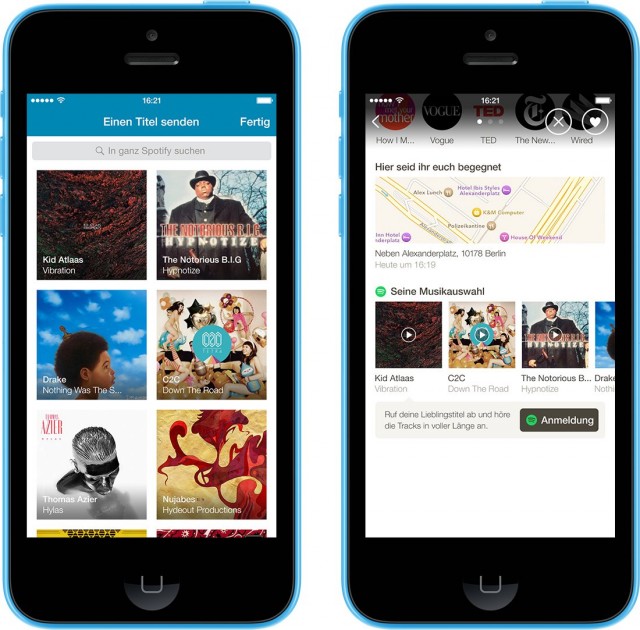

Happn, a Paris startup that lets you anonymously message random people you see on the street (not at all creepy), now lets you send music to those people.

Now, this may or may not be the future of dating.

But if you’ve been following the lead-up to the roll-out of Apple Music, seeing this might lead you to some other questions.

First, regarding Apple music specifically:

1. Will Apple Music integrate with other apps? Apple Music lacks an API. And that means, at least from the developer / music hacker perspective, it’s a heck of a lot less interesting than other apps. Sure, Happn’s application might be a bit silly, but this is the beauty of developing stuff: you can try silly ideas, crazy ideas, and eventually might stumble on a great idea. It doesn’t necessarily lock out Apple Music integration with other apps, though – maybe Apple will allow the use of Android intents or iOS’ Share function.

2. Are people overestimating Apple’s ability to unseat Spotify? Spotify has already become synonymous with streaming music. And that means people have assembled friends, playlists, collections, and listening habits – none of which can be transferred to Apple Music. I think Apple’s effort here, and the Beats acquisition, are partly admissions that even one of the world’s biggest companies can face real competition on the level Internet playing field.

And streaming more generally…

3. Could new applications mean people listen to more music? Streaming fees are paltry, it’s true. But even if Eternify’s application was dumb and eventually shut down, it does illustrate another point. In the post-album world, you might have the same music in more places. It might be in games, it might be in dating apps. It might be that you go to a cafe and finally get to determine which music you hear, jukebox style. Generate more apps, and capture more data about what’s played, and collection fees could become more relevant to independent artists.

4. Could revenue come from places other than playback fees and purchase price? Here’s where things get really interesting – slash – mysterious. Having grown up, most of us, in the age of vinyl records and tapes and CDs, we tend to think of the musical album as the product – the thing you buy. But if music becomes a service, that may not be the case at all. As many have predicted, this might lead people to purchase of other stuff, from swag to concerts. Even that, though, takes a traditional view. Someone may find a different direction entirely, once the music itself is flowing wherever you want. (Remember that ring tones were briefly big business, so you never know what business models people may make work.)

5. How can listeners feel they’re connecting most directly with artists? I think this is the biggest question of all. Apple paid a lot of attention to this in their Apple Music announcement, but much of that had to do with artists giving away still more stuff for free. From Kickstarter to Bandcamp to Etsy to Vimeo purchases to boutique synths, the Internet has again and again demonstrated that people are often more willing to invest money in something they love if they feel that money goes directly to the person who made what they’re buying.

Well, in the meantime, I’m going to keep using Bandcamp, iTunes purchases, Beatport, and direct stores to buy downloads.