Forget about whether anyone is going to listen to that release, let alone whether you’ll make money. Finishing is a beautiful feeling. Something happens when you get to that phase of adjusting the final mix, bouncing for mastering.

For many of us, that last step involves a stereo bounce. But I think it’s high time to start thinking in terms of stems (both in the lowercase, and the all-caps STEMS Native Instruments is keen for you to use).

Stems, lowercase, are terrifically useful if you want to be able to involve others in remixing your work. (Or if you yourself want to make remixes later.) And in everything other than Traktor, some number of stem files can be added to a multitrack environment for live sets. That includes hardware with multitrack playback capability, and things like Ableton Live or FL Studio or anywhere you may organize a live set.

STEMS, in caps, are still for now limited largely to Traktor for playback. (Correction: one exception is Flow 8 Deck – see bottom – interesting new DJ software that I hope to review, plus on mobile DJ Player Pro.) But that might still be enough reason for you to take a few moments to produce them.

I’m putting the two together because it’s kind of stupidly simple to produce both stems and STEMS at the same time.

STEMS and the rule of four

We’ll take into consideration Native Instruments’ format STEMS, because it can be a useful template for stems in general.

The important thing about STEMS as a format is, you only get four stereo stems. This is a way for NI to standardize, and to make file size and controller mapping more manageable. Now, before you get up in arms, I think four is a very good number to start with.

STEMS by default suggests “drums, bass, synths, vox” as the four stems. The idea is to swap out whatever you may need for your particular track – it could be “accordion, jaw harp, found sound, humpback whale” or something in between.

But I find it useful to start with this template, because my goal in producing stems (now lowercase) is to simplify. If I’m using the stems myself, simplifying generally keeps some coherence to what I’m working with. If I’m sharing them with someone else, that becomes even more important. (Lesson learned: when you make too many tracks and then hand them over to someone to remix, what you get tends to be… a production that sounds nothing like your original track.)

Now, once starting with four, you may find that five is really a better number – so then you can still divide out the stems for use separately from STEMS.

Finishing with stems

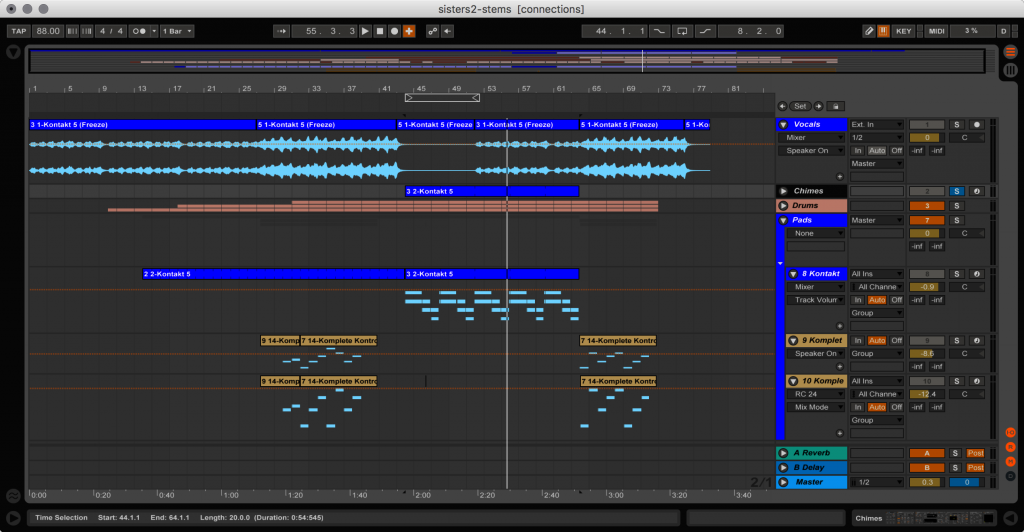

Here’s the bit I like. In Ableton Live, for instance, grouping tracks involves first dragging tracks together so they’re in a logical order, then assigning them to groups. Once grouped, of course, you can easily solo individual stems to hear how they sound on their own.

I like this part of the process because it tends to be a good chance to reevaluate the mix and (erm, in my case) clean out a bunch of illogical and extra tracks that get accumulated during the composition process. Having watched other people work, I notice a lot of us get into similar habits.

Why producing STEMS is a good idea

Disclaimer: having praised STEMS in the past as a format, I really have no idea whether it’ll catch on in the real world as far as the music market goes.

There are plenty of obstacles to STEMS getting any (cough) traction. STEMS purchases now cost more than individual stereo tracks. That might seem like a good opportunity for more revenue, but I expect some purchasers are economizing by just ignoring it. And I think the average DJ still has no clue about STEMS – what they are, why they’d want them, or how to use them. Stereo files still remain the lingua franca – they work on USB sticks and CDJs, they’re what you’re likely to get as a demo/promo, and so on.

But your job isn’t necessarily to predict the future of DJing. So here’s why you might give them a go anyway:

1. You can probably master STEMS for free – and submit them accordingly. I was pleasantly surprised to discover this is the case with my mastering engineer of choice, Berlin’s Cem and Jammin Masters. (Maybe being across the river from Native Instruments doesn’t hurt.) You’ll see some mastering partners already on the STEMS site. And if not —

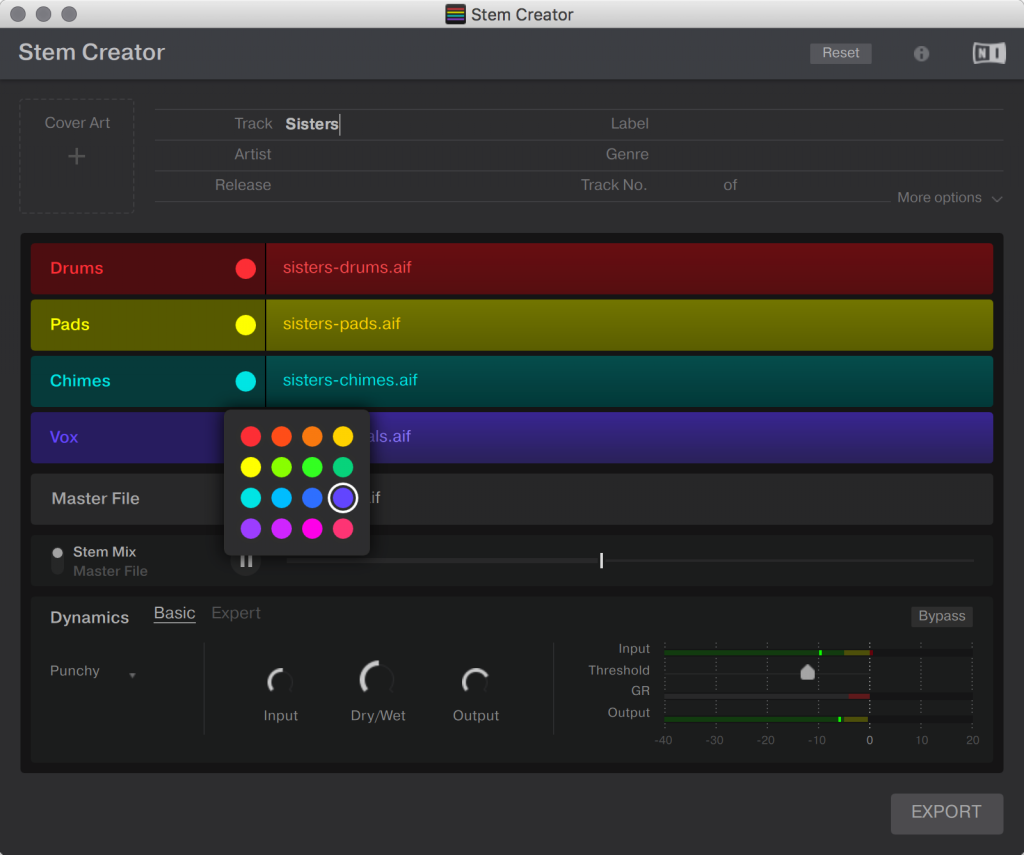

2. Doing it yourself is pretty easy, too. NI has made the StemCreator tool idiot-proof. Drag and drop your four stems files, plus your stereo mix, and you can A/B them until the mix of the stems is just as loud as a master. This alone ought to give you reason to try STEMS (see item #4), because I suspect often the reason producers DJ or play live with the stereo master is that it sounds louder. Here, all the dynamics tools are built in and you can solve the mix in a few moments.

3. They’re easy to distribute. All the major online stores have STEMS support now, and they’re easy enough to offer up as standard downloads in Bandcamp, etc., too.

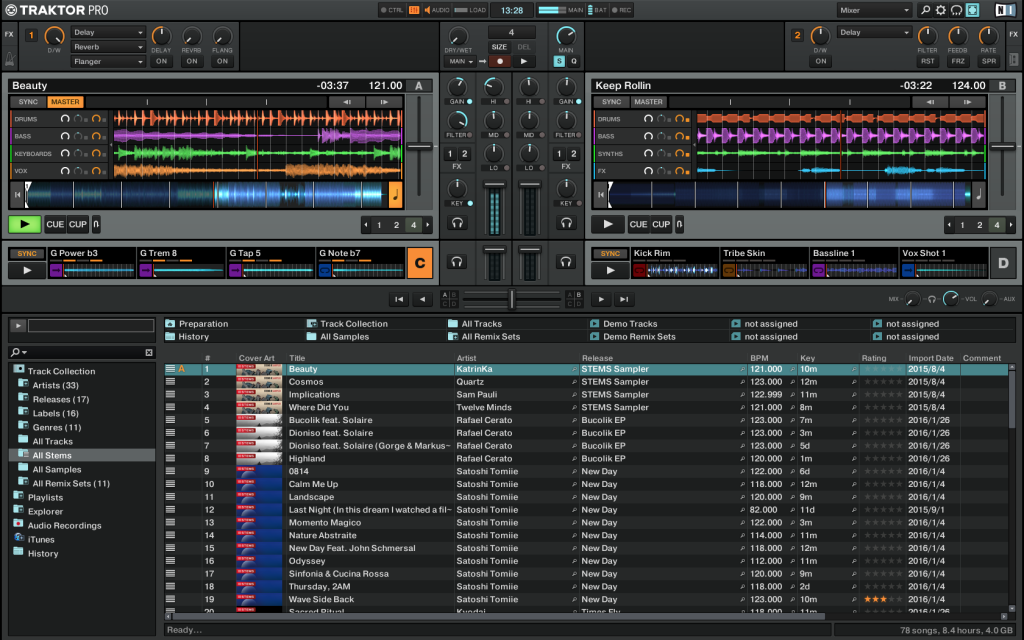

4. If you have Traktor (or another of a couple supported players), you owe it to yourself to give it a try. Oddly, I have been listening to DJ legend Mijk van Dijk evangelize this on Facebook. Whether or not you want to use anyone else’s STEMS, using your own STEMS in Traktor is a revelation. It’s a terrifically easy way to pull apart your own music and blend it with a DJ set, far easier than the clunky ways of doing this in Ableton Live. I love Live – it just isn’t designed for this particular task. And watching producers try to force it to do something it isn’t good at, watching over shoulders in DJ booths, I find kind of painful.

Again, if you’re not sharing your tracks or you don’t use Traktor, you can safely ignore STEMS (and stick to “stems” lowercase). But for anyone doing distribution or working with Traktor, for now, it’s something you can do “for free” and with minimum time involved.

NI are making STEMS easier to use

This week was a good week for STEMS in Traktor, thanks to a Traktor update and accompanying promotion:

- Now you can see STEMS on screen. Pictured, above. Previously, the waveform view in Traktor stupidly showed only the stereo mix. Without a D2 or S8 hardware, the content of STEMS was invisible. That’s now fixed in the latest free Traktor update – finally. I don’t encourage staring at your laptop while you play, but this is still welcome.

- And it works with the S4. Again, previously mappings worked only on the D2 and S8. Now the S4 works, too, out of the box. Good. But you don’t have an S4?

- You can map any controller you want. I love my tiny Faderfox controllers, and I’m fancying doing some DIY hardware. You probably have a controller you want to use. Now, also under the heading “finally,” you can assign any hardware you want, so STEMS isn’t just about making you buy some new NI box.

- And you get a bunch of tracks for free. This isn’t the Maschine integration a lot of us dream of, but at least you get 1.5GB of building blocks from various genres to use to try STEMS.

- Plus a coupon and some videos. NI also are offering a discount off online stores to buy more STEMS (if you’re into that), and some videos.

Have a look at how this works:

To me, the really big draw, though, is producers being able to work with their own materials. So some producers I’ve talked to are using STEMS just as an additional way of getting their own loops and content into Traktor – not even stems of complete tracks, per se.

More info on that special:

http://www.native-instruments.com/en/specials/stems-for-all/

STEMS beyond Traktor

There’s a role for a format like STEMS to do more than plain audio stems could do on their own. With an actual format for exchanging files, you can ensure consistent playback, hardware mapping, and dynamic levels. That is the potential power of STEMS as a “standard” – and there’s some benefit if it works in more than just Native Instruments products.

The format itself is not proprietary; it’s already a standard container format and encoding, as I’ve written before. And that’s a good first step. But to fully support STEMS, software needs to be able to play back the mix of the individual stem tracks so they sound consistent with the stereo mix.

The reason for the moment STEMS support is primarily in Native Instruments products is because third parties are awaiting an SDK that allows them to do that easily. The SDK will provide the same dynamic processing components, so that your mix sounds the same regardless of which tool you’re using.

In a statement to CDM, Native Instruments tells us that SDK is near release:

“NI is very close to have a release of the SDK. We have given out the SDK to a few selected 3rd parties as a first step – including manufacturers of DJ software and hardware. We have already received a very promising amount of inquiries around the SDK, not just from developers, but also from educational facilities. In the next weeks, we will distribute the SDK to more and more development teams around the world.”

That’s promising news, for a couple of reasons. The indication that partners are already involved suggests that we could soon see STEMS as a interoperable format across other players in the industry. And the public availability of an SDK opens up the possibility of surprise applications for STEMS beyond that. (iOS developers, for instance, have proven a versatile bunch.)

In the meantime, demonstrating that the file format is open, there are a couple of (unsupported) apps with STEMS support, as readers pointed out: DJ Player Pro on iOS and Flow 8 Deck on desktop. But a full SDK would make implementation more consistent and predictable.

It’s too soon to judge until that SDK is available or other partner announcements are made, but we’ll be watching.

And of course, this means that preparing STEMS files now could make them more useful later. Let us know if you do that, and any interesting ways you find of working with STEMS or just “stems” – and if you have other questions.