Electronic sound is in theory a limitless blank canvas. Iannis Xenakis and his work imagine what image of sound could fill that page – and leaves a legacy that’s still radical today.

Now, we get a view of those multi-faceted possibilities from an array of angles, in a new book from the legendary ZKM Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, Germany. The book is available digitally, for free, as downloadable PDF (along with other archival materials). These accompany the print edition, just released today.

From Xenakis’s UPIC to Graphic Notation Today

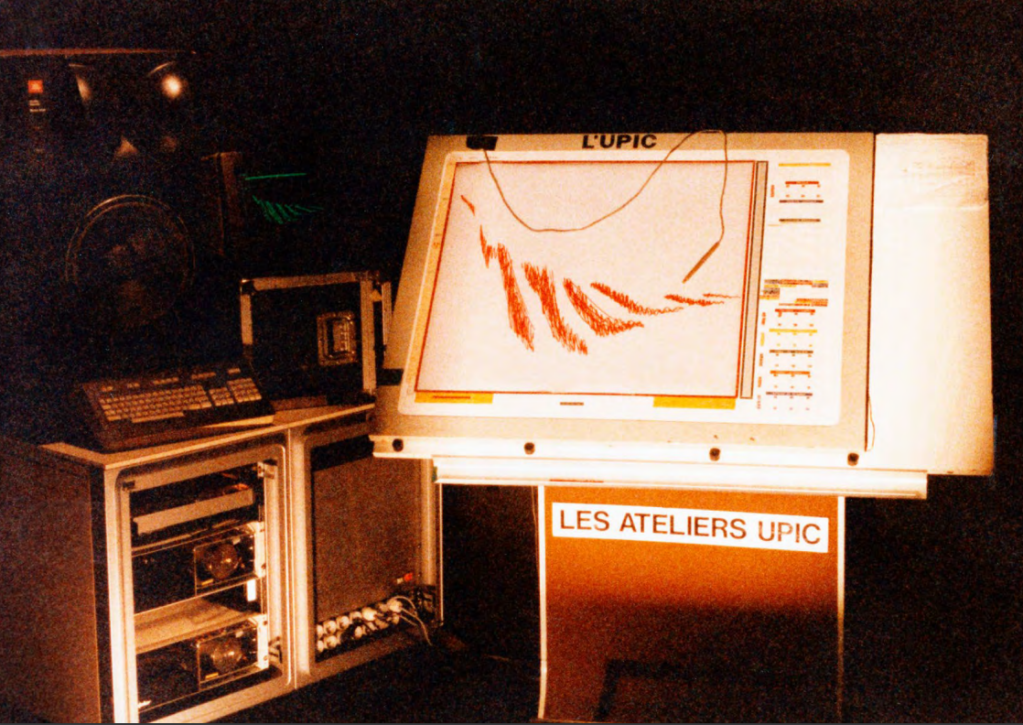

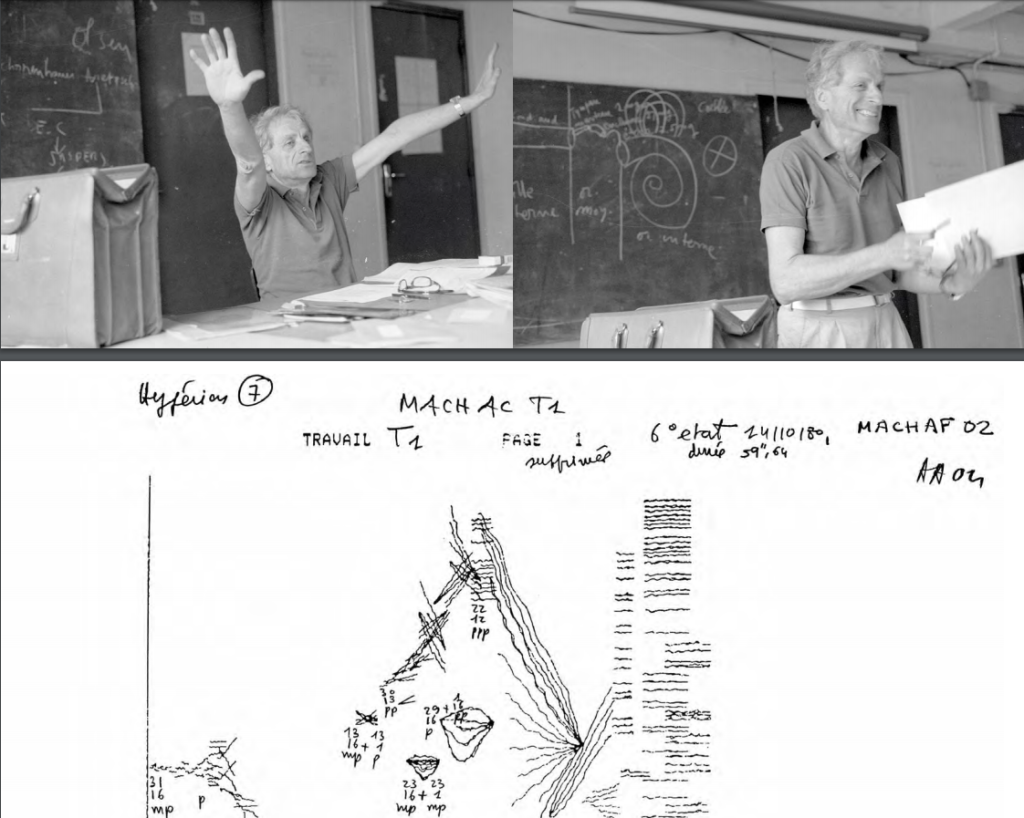

If you don’t know the UPIC, it’s hard to overstate the importance of this invention, originally seen in 1977, whose impact touched everyone from Risset to Aphex Twin. Its breakthrough was to let the composer draw with sound – paint with the tablet, and the results are synthesized in pitch and time. We’re actually so used to the concept now that it might even be tough to see this as an invention. But thanks to Xenakis’ larger compositional work and the extensive writing and teaching he did and other instigated, any real odyssey into the world of the UPIC winds up being a saga into digital art and sonic interface, how to make and teach them.

The book is a journey through graphic notation and visual interfaces for music across nations and decades, as well as a comprehensive look at Xenakis’ own work, and its influence and use in education. There’s a star-studded media art editor lineup helming the project – ZKM’s iconic artist/curator/theorist Peter Weibel, pioneering composer/electronic musician Ludger Brümmer and musician and Xenakis scholar Sharon Kanach.

Kanach’s work is already familiar to any Xenakis nuts – not only did she work closely with Xenakis himself, and translated his writing, but co-authored with him the other must-have Xenakis text, Musique de l’Architecture (2008) along with working on editing enough texts to fill … well, a building, actually.

In another decade, all of this might be seen as archaic academic stuff. But now we live in a world where experimental sounds and post-tonal timbres sing and scream into dance music charts and popular music. We see visual interfaces – once confined to Xenakis’ unique machinery – as commonplace as we do a music stand or manuscript paper, if not more so. They’re on computers and free software and iPads and phones, recognizable by people on the streets in every populated continent.

And in the meantime, the aficionados of Xenakis and graphic notation have taken those once-marginal ideas about image, interface, and graphic music and brought them to apps and schoolkids. That poetry is accessible to everyone.

ZKM’s tome begins its story with the origins of the UPIC, the strangely ahead-of-its-time machine Xenakis engineered with a “musical drawing board” that could blur the line between score and interface. You can read the book as a complete background on the history of that instrument and its influences.

But the full context is here, too. And what makes it special is that this is not just a detached theoretical text, but written by people who have gotten their hands on the machines.

Andrey Smirnov, best known for his intensive background and advocacy of early Soviet experiments in graphic music, weaves together a rich yet breezy overview of the interconnections of ideas around the globe in graphic sound. Smirnov’s prose is uniquely readable in part because it easily switches between the mechanical engineering reality of these machines and their more philosophical, even spiritual conception – without missing a beat, either way.

Guy Médigue, who worked on this machinery in the 70s, gives an accessible but comprehensive explanation of everything from acoustics to technology in his essay. It’s a class in a chapter. It’s also worth watching him speak at ZKM, apologizing for his English, yet lucid in everything he says:

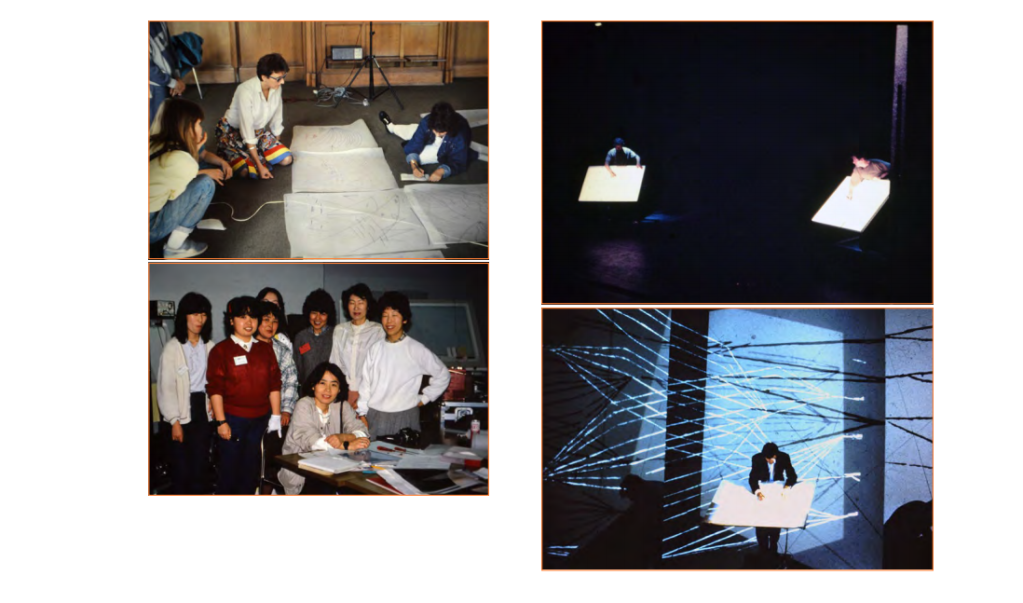

There’s also the perspective of composers and teachers – teachers of composers and teachers of kids – for a view of technique and pedagogy. It’s a chance to see this not only as a monolithic composer and machine, but a set of ideas that grew out of it and continue to travel.

And there are deep conversations about institutions, resources, and the challenges of supporting experimental music invention inside the society. Katerina Tsioukra aand Dimitris Kamrotos describe the ups and downs over the history of UPIC and its experiments in the composer’s father-and motherland, Greece. Too often it seems those conversations aren’t translated or that international audiences simply disregard them. Now, with Europe in new crisis, it seems an essential time to examine these fragile links. It’s important reading for anyone working in nonprofits, cultural diplomacy, curation, and the like.

Pointing the way to the future, roughly half the text is devoted to exploring the ideas the UPIC presented, and its relevance to new interfaces and composition and the larger world. Kiyoshi Furukawa investigates utopia, artwork, and architecture. Chikashi Miyama builds as convincing a family tree and conceptual map as I’ve ever seen, compromising the UPIC canvas and other graphic interface and digital art idioms, as well as the various UPIC descendants, like IanniX and UPISketch. (Julian Scordato goes deep into IanniX, for someone wanting to try this hands-on now in software.)

This topic could easily become deeply academic, but writers like Victoria Simon make it visceral – connecting to the composer’s own personal views. Her essay on the tactile begins with this challenge from the composer:

“It is necessary to relearn how to touch sound with one’s fingers. That is the heart of music, its essence!” –Xenakis

This was 1951-53, long before the Dynabook, let alone the iPad… and it just as easily could be viewed as an admonition to get more tactile still.

I can’t wait to read thoroughly. Marcin Pietruszewski’s “digital instrument as an artifact” sums up about half of what I’ve ever tried to work on in the title, so… there’s that.

The site is accompanied by music examples, too – fantastic avant-garde sounds that many readers of this site will love. Oh and – if you happen to be in lockdown with someone who’s getting on your nerves, and that person is not into avant-garde sounds, nothing says “oh, I really should catch up on my exercise routine with some headphones on” like blasting Eua’on’ome. (Hey, I’m just performing a public service here. You’re welcome.)

But it’s a joy to have this arrive now. Nothing can pierce the darkness or fight loneliness quite like sound and ideas. I hope it reaches some new shores.

https://zkm.de/en/from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today

https://zkm.de/en/event/2020/04/book-release-from-xenakiss-upic-to-graphic-notation-today