How did the Minimoog take shape – and set the course of synthesizer and musical instrument history? Among many revelations in JoE Silva’s The Minimoog Book for BJOOKS, we learn how the synth’s early prototypes evolved into the instrument we know today. Read the excerpt here.

Michelle Moog-Koussa collected a crucial document that provides a missing link in that story. It’s about the transformation of the Model B into the Model C – the evolution of the panel into the iconic design that has shaped synths to this day. But it’s about more than that. You see the collaboration of Bob Moog with Bill Hemsath. You get a greater sense of Bob’s vision for the instrument and synths more broadly – looking to horizons even beyond those the Minimoog would reach. And you get to see the thought process as the instrument came into being.

“When you hold it in your hands, there is an undeniable sense of the extraordinary historical significance held within its pages,” Michelle told me about the document.

It’s also a perfect example of the importance of the Bob Moog Foundation. Their archival and educational work reaches across music, engineering, science, and creativity. And it’s a testament to Michelle’s vision and dedication, too – and why we’re indebted to her as well as her father.

You can support that work. As I write this, there’s another 24 hours or so to enter the Bob Moog Foundation raffle for a unique $20,000 Eurorack modular system and some other prizes. Or any time you can try membership and the shop.

And if you’re quick, you can get a signed copy of The Minimoog Book signed by JoE Silva:

That book is a synth adventure. If you think you knew the Minimoog, its builders, its history, and the artists who played it – I mean, I thought I knew at least some of that, and flipping through the book, I began to grasp how much more there is to discover.

On to the excerpt – courtesy Bjooks.

Images and historical documents courtesy of the Moog Family Archives. All images and historical content reproduced with the permission of the Moog Family Archives and Bjooks; text courtesy Bjooks.

Excerpted from JoE Silva – The Minimoog Book. All photos by Bryan Redding. (Document photos by the Bob Moog Foundation.)

Michelle Moog-Koussa at work with the archives. Courtesy of the Moog Family Archives and Bjooks. Photos Bryan Redding.

The Missing Link

When Michelle Moog-Koussa got a call from a family member asking if she wanted several boxes of random paperwork found in her father’s office after he passed, there was zero hesitation on her part. She was quite used to preserving and examining her father’s papers to determine if they should be added to the Bob Moog Foundation Archive.

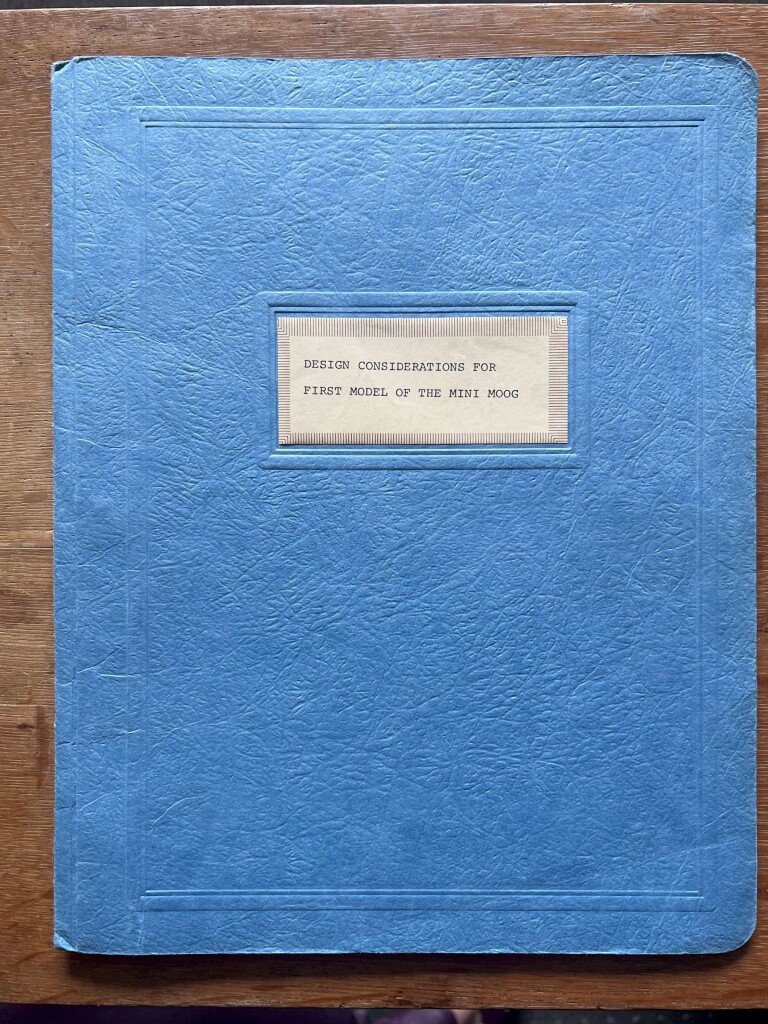

Still, once she took possession of the materials, she couldn’t have anticipated the thin blue binder that she pulled from one of the cardboard containers:

“DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS FOR FIRST MODEL OF THE MINI MOOG”

The document cover. Courtesy of the Moog Family Archives.

She knew it existed and had seen it at least once before, but finding it in her father’s papers came as a total surprise. This was clearly a unicorn – an internal document about one of modern music’s most prominent instruments, written before the company had even settled on the spelling of the name.

“The first model of the Mini Moog is an electronic musical instrument which incorporates many features of studio model synthesizers. The circuit components are made available to the musician in such a way that he is able to combine them in a large number of ways to form a large variety of sounds.”

This statement of intent had been hammered onto frail onionskin paper almost 50 years before Michelle had discovered it, but it was all there – a complete discussion of how the circuitry should come together, what accessories the synth could connect to, and how musicians could interact with it.

“The first model of the Mini Moog is an electronic musical instrument which incorporates many features of studio model synthesizers.”

“DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS FOR FIRST MODEL OF THE MINI MOOG,” 1970.

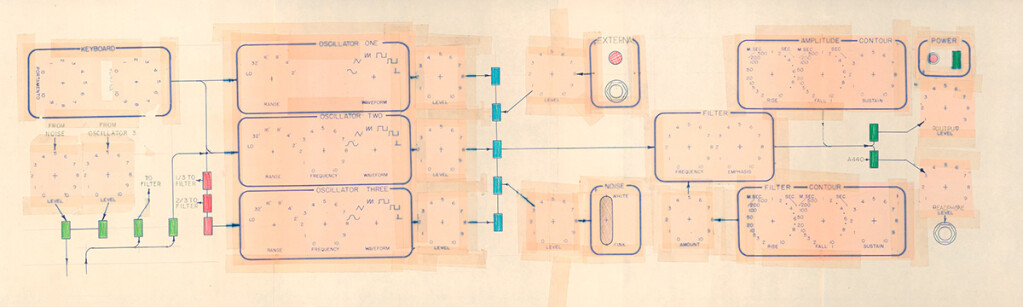

While the document’s taped-together foldout diagram [below] shows a layout somewhere between the Model B and Model C, nearly half the document is an extensive description of the new keyboard’s features, which closely match those of a Model C. Initially, the design called for at least two sliders on the left side of the keyboard to be used for pitch control and modulation, in conjunction with two “doorbell” style buttons to engage portamento and sustain. A third and fourth slider were proposed to respectively control brightness and loudness. Other suggestions included controls mounted below the keys, as on an organ, and collapsible “legs or stands” so that it could be accommodated on top of another keyboard or stand on its own.

Fold-out diagram of Minimoog panel layout. Courtesy of the Moog Family Archives.

Additionally, the design document forecasts the possibility of two versions of the synth, one for professionals and one for “quasi-professional entertainers… who will constitute the largest single market.” In all capital letters, the document also stipulates that there be “NOTHING DELICATE OR VULNERABLE” about the synth, so that it could withstand the rigors of regular use in a live setting.

As to the overall appearance of the synth, Moog was fine with the pro model coming across as “flashy and showy, perhaps even a little vulgar” while the home model should “have a suggestion of adventure, like a Rolls Royce Convertible.”

All told, the hope was that all of this could be done for about $25 per pro unit, of which they estimated selling between 500 and 5000, while the fancier home unit might sell between 100 and 500 units and hopefully cost the company no more than $50. Plans for two to four more instruments in the line, including a two-tiered five-octave version and a percussion instrument, are also mentioned – with projected delivery as early as the following year.

Model A. Image courtesy Bjooks and EMEAPP.

A modest proposal – but for what?

It’s not entirely clear what the document was created for in the first place. It might have been a spec overview for internal use, or one that R. A. Moog may have intended for an outside company under hire to produce the final product – hence the detailed specifications, and also this statement:

“This won’t be an easy job, and will have to be done with constant consultation with our engineering department.”

A likely possibility is that this was a pitch to entice potential investors (like Bill Waytena). Language is chosen to make the new instrument seem an attractive proposition, especially the projected sales: 5000 units or more, even though internal projections were more like 200 (p. 46).

Furthermore, there are no date references in the document, no mention of “after building two prototypes…” or the like, to indicate when in the Minimoog’s timeline this document was put together.

However, it’s a fair assumption that because of the radical design shift between the Model B and C, what was forecast across these nine pages occurred after Bill Hemsath and Bob Moog – who are both given credit as having prepared the document – had sat down and given serious consideration to how a finished version of the Mini would look and function.

Bob was not a collector. There was no secret room, he didn’t have a garage stuffed with old modular synths and circuit boards, and considering the rocky path his exit had been from his old company, it wouldn’t have been terribly surprising if he hadn’t held onto many career artifacts from the past. Yet this design document came along with him through the decades – despite any initial reluctance he might have had about going ahead with the Minimoog project when it was presented to him.

When the Model D was resurrected by Moog Music in 2016, it was important to the company that the 21st-century Minimoog met the same exacting standards as the original. Despite a few small tweaks, they chose not to go too far beyond the design that had been laid out more than 50 years ago in this slim blue binder – because those ideas, like those thin pages, had not yellowed with age.

Model B. Image courtesy Bjooks and EMEAPP.

A draft for the control panel interface

The last page of the blue binder is the foldout diagram above. It clearly shows a mockup of the proposed instrument’s front panel, with various graphic elements cut out and taped to the paper and colored pencils used for marking similar functions – like the blue mixer switches.

The Modifiers section has familiar knobs for Tuning and Portamento (later renamed Glide), and two separate knobs for introducing Oscillator 3 and Noise modulation, which would eventually be replaced by a single Modulation Mix knob.

The Oscillators offer identical waveforms, including a sine wave and without the saw/triangle option. The modulation and keyboard tracking switches haven’t been moved to their final places yet.

Finally, while the red Overload light on the External Input is shown prominently in the location it would have on the Model C, the input jack itself is located on the front panel rather than the rear.

A side-by-side comparison of the front panels of the Model B (above) and Model C (below) clearly shows how the foldout diagram represents a crucial step between the old design and the new, changing some features and moving others to arrive at the Minimoog’s iconic front panel design.

Model C. Image courtesy Bjooks and EMEAPP.

A surprise announcement

It’s almost certain that the design document was completed before or during the Summer of 1970, because of the publicity that came later in the year about upcoming events.

Bob’s comfort level with the coming additions to his product line must have been on a gradual rise, because in the run-up to Dick Hyman’s MoMA concert in August, the company openly acknowledged those changes to Billboard, the US music industry’s leading trade magazine.

Under the headline “Mini-Moog to Be Unveiled at Museum,” the news article pointed out that the “mini-Moog – ‘a synthesizer the size of an electric office typewriter,’ invented by Dr. Robert Moog, will be unveiled Aug. 20 at a concert in the Museum of Modern Art.”

The piece went on to say that the new instrument would go on to retail for about $1500 and that it would be “the first of several models.” Other details, including specifics about the types of features the new keyboard would have (tunable keyboard/oscillators, white/pink noise…) were laid out and concluded with Moog’s proclamation that:

“It’s a compact system, employing all the basic tools used in electronic music composition.”

The news may have been buried on Page 8, but the word was out. Not that everyone in Bob’s circle was in on the changes: Walter Sear, Moog’s first and biggest sales rep, apparently knew nothing about what was going on in Trumansburg, even though he was actually slated to help engineer Dick Hyman’s MoMA performance.

“A synthesizer the size of an electric office typewriter,’ invented by Dr. Robert Moog, will be unveiled Aug. 20 at a concert in the Museum of Modern Art.”

Billboard, 1970.

Model D – serial #1001. Image courtesy Bjooks and EMEAPP.

Successes of the past, dreams of the future

In his interview on Pacifica Radio, Bob didn’t just talk about the new portable performance synthesizer he was proposing. He also touched on past accomplishments as a prelude to his synthesizers’ future development.

“Last year we gave a couple of concert demonstrations that were exploratory in nature, in which our standard synthesizers were equipped with preset program boxes which enabled the musicians to play and change rapidly from one tone color to another without going through the patch cord changes and control setting changes.

“What is actually needed is a series of specialized synthesizers designed for live performance. These synthesizers would include the capability of calling upon any combination of control settings and patchings that could be pre-programmed to the device… calling upon these instantly by pressing one button, say. It would also involve manual controllers, such as keyboards that were sensitive to as many directions as the hand could move, not just up and down. Finally, it would be stable and accurate so that it wouldn’t have to constantly be retuned.”

“What is actually needed is a series of specialized synthesizers designed for live performance.”

Bob Moog, Pacifica Radio interview, 1970

While some of those advancements were years away in technological terms, the design document hinted at the possibilities, painting an exciting picture of the future.

Thanks to Kim and Michelle for making this excerpt happen – and a huge debt to JoE Silva for this spectacular tome. Here’s Michelle talking about getting to discover her father and his work:

Those incredible Minimoog images come from another great platform – the Pennsylvania-based nonprofit Electronic Music Education and Preservation Project (EMEAPP). Let’s include one more – this is Herb Deutsch’s Minimoog, from the Bob Moog Foundation collection.