Let’s face it: the initial audience for the first version of music tech is often the developers.

That impulse to build something for yourself is a perfectly reasonable one. But music technology is constantly producing new ways of creating music, and that means it has to learn quickly. Unlike, say, a guitar, it can’t build on centuries of experience.

And if the industry and music technology community are to consider how to reach more people, why not go beyond just average markets? Why not open up music making to people who have been left out? If music making is an essential human passion, fulfilling a need to self-expression, that means not just allowing casual use or making toys. It means really finding what can make tools work for people who might otherwise be ignored.

As the NIME (New Interfaces for Musical Expression) conference is underway in London, it’s a perfect time to catch up with our friend Ashley Elsdon. Best known to readers here as the man behind Palm Sounds, a herald of mobile tech that preceded even the iPhone (hence the name), he’s got a different project here. It involves mobile tech, but with a new goal in mind.

SoundLab focuses on those with different abilities – particularly learning disabilities – and tries to make all these tools work for them. The results are encouraging – and, very often, futuristic. It might hold some answers to how to make better-designed musical instruments for everyone. Ashley here explains the project to CDM. Here he is… -Ed.

SoundLab Forms a Mission

Making musical expression accessible to a much wider audience is something I’ve been passionate about for many years, and it’s something that I believe is fundamental to the mobile music community. So when I got asked to be involved in a year-long project to research how to improve access to creative digital tools for people with learning disabilities, I obviously jumped at the opportunity.

The project is called SoundLab. It is focused on finding simple and effective ways to help people with learning disabilities to express themselves musically and collaborate with other people using readily available musical technologies. That’s quite a broad remit, especially over less than a year, but I’ll explain more about what the project is trying to achieve as we go and hopefully it’ll all make sense.

2013, SoundLab in pilot …

SoundLab is a much-expanded version of a project I worked on in 2013. Last year’s work was more focused on using iPad apps, and it culminated in SoundLab being a part of a huge event called the Beautiful Octopus Club at the Royal Festival Hall on London’s South Bank.

The 2013 event went far better than we’d expected, which presented some issues. We’d expected users to want to play with our different configurations of iPads for just a few minutes at a time. However, this was not the case. At some points, we had queues to come in and play. So I think it would be fair to say that we’d underestimated the appeal of this kind of music making, and we certainly underestimated the range of people who were keen to try out what we had on offer.

SoundLab 2014

This year is much bigger and has a much wider scope than our pilot last year. As previously mentioned, SoundLab has a very broad scope. So our first step will be to evaluate a number of technologies, from gestural controllers to iPad and other touch-based devices together with a wide range of apps and other enabling software. The goal is to work out what the best and most appropriate combinations and configurations of technologies are for different groups of users and in different working environments. We’ll do this through both closed workshops and larger public events, such as the Beautiful Octopus club.

The first step is to arrive at a matrix of configurations that shows the best available hardware and software for any given combination of users and environment. Then, we’ll start to look at how we can build a software framework to enable educators and facilitators to make the best use of these technologies without having to be a technical expert. In addition, we’ll create a best-practice guide that will be available to anyone with an interest.

So that’s the plan. We started in May and we’ve already held two workshops, and we’ve learnt a lot already about the interfaces we were using. We’ve launched our new website makeyoursoundlab.org, and we’ve had great responses from companies who want to be involved in supporting our work.

IK Multimedia sent us loads of iPad stands for our workshops and also their new iRing controllers, which have already been really popular. We’ve been promised two Synth Kits from littleBits who really saw the value in what we’re trying to achieve, and Moog are sending us three of their amazing new Thereminis which are going to be really useful in our workshops and also in our public events.

If you’d like to be involved by donating hardware or software, please do get in touch using the contact form on our site. The sooner we hear from you, the better, as we’re running our workshops all over the summer and so ideally we have new equipment to test with our users as soon as possible.

If you want to keep up to date with what we’re doing, you can use the news blog on our site and we should have a Twitter account up and running soon, too. Hopefully we’ll be able to update CDM around the autumn with how we’re getting on.

CDM: What are some of the target users? (That is, what sort of accessibility are we talking?) Who have been some of the participants?

When we ran SoundLab last year, we ran a series of workshops with users with a wide range of abilities, both physical and learning abilities. Our target user groups are adults with learning disabilities, but what’s really important to understand is that as you develop improved methods of providing access and interaction for someone with learning disabilities, you in turn benefit a much wider group of users, by providing better accessibility and simplicity of use.

What are some of the actual apps / tools you’re using, apart from the donated ones you mentioned?

So far we’ve been using a number of hardware interfaces in the early stages of the project. We’ve experimented with:

- Leap Motion

- Gametrak, a now-defunct 3D controller

- [Microsoft] Kinect

- IK Multimedia’s gestural controller iRing

We’ve also found a number of iPad apps work especially well. These being:

What has been different about these applications from others that aren’t focused on accessibility? Can you give any concrete examples of how you’ve tailored music making to a particular person?

In terms of the apps above, they stand out for a number of reasons. Apps like Thumbjam and Bebot can be played with no understanding of the app; a user can create sounds that provide them with a positive experience in no time at all. This is similar with Loopseque, although with this app, we’ve used it as a backbone in a ‘digital band’ setting. Loopseque worked well as again its interface required no extended learning and also provided immediate visual feedback for the user. This was especially useful in a busy live event, as we had a large number of people coming through and using apps with no experience of either music making apps or, often, of iPads, either.

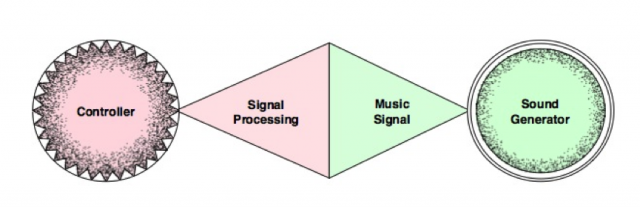

In our current project, our end objective is to be able to provide a kind of middleware for music interaction software. A layer that can be used by educators and facilitators to easily combine physical technologies such as Kinect, iRing, etc. to a machine learning layer that can pass data on to any sound source.

See image for an explanation, schematically:

For more:

http://www.makeyoursoundlab.org

http://www.palmsounds.net/2014/05/pictures-from-sound-lab-1.html

Thanks, Ashley! We’ll be keenly interested to follow this one! And we look forward to reader feedback, whether you’re a developer or user, whether you’ve done user testing like this before or have specialization in this field and have done similar work, or whether you yourself or someone you know have accessibility requirements you’d like to see addressed. -CDM