In fragmented materials and process-based performance interventions, this year’s Berlin Atonal exhibition seems to breathe life into debris, a deconstruction of ruined objects. But most striking of all is the work of sound artist Rabon Aibo. With mechanical constructions, he makes the cavernous Kraftwerk power plant into an instrument – and makes use of gas canisters that resonate with dark moments in both Kurdish and German histories.

Photo: Helge Mundt.

To me, it was one of the most moving moments I’ve had in Kraftwerk – as hard-hitting emotionally as sonically. Sound interventions for Rabon’s work occur earlier in the afternoon, but an array of mechanical percussive devices come to life just following Romeo Castellucci’s video art meditation on fascism and aggression, unsubtly titled The Third Reich. As the din of that piece subsides, solenoids scattered through Kraftwerk’s industrial architecture tap and clang away at metal beams.

Kraftwerk’s architecture is so resonant, its reverberation so pronounced, that delicate sounds tend to be easily drowned out. The “playing the building” notion may be familiar – think back to David Byrne’s 2005 installations in Sweden and a disused NYC ferry terminal. But what’s unique is Rabon’s sensitivity to the history of his objects — and his craft in making these fragile sounds clear in a space that would easily swallow them.

It is as though the skeleton of the building is rattling to life – the clatter of the bones of the structure. The gas canisters stand in a spotlight like sentinels, casting shadows across the floor in almost human silhouettes. And there in a prominent position at the center of the flow of audience from ground floor to the stage, they silently confront the public.

Rabon wrote about his work to us in the midst of dances of installation setup and tending to batteries.

Photo: Anna Eskandar.

CDM: Your installation is all over the space – and moves, even, to a different configuration for the exhibition and show nights. How did you begin to explore that and what might work? Were there any surprises?

RA: The space has a cathedral effect, if you experience it for the first time. I remember very well how the architecture of the building immediately resonated with me. Some buildings radiate a very unique sublimity and the Kraftwerk building is one of them. And this is also true for the sound aspect of the space.

Acoustically, the place is very challenging. For example, if two people are talking to each other and they are standing at a distance of 10 meters, you will not be able to understand what they say. There is this special type of hall effect blurring the acoustic phenomena and I knew I wanted to explore that.

Have you worked with this kind of medium before? Or how would you relate this to some of your other practice – both with sound art and playing live?

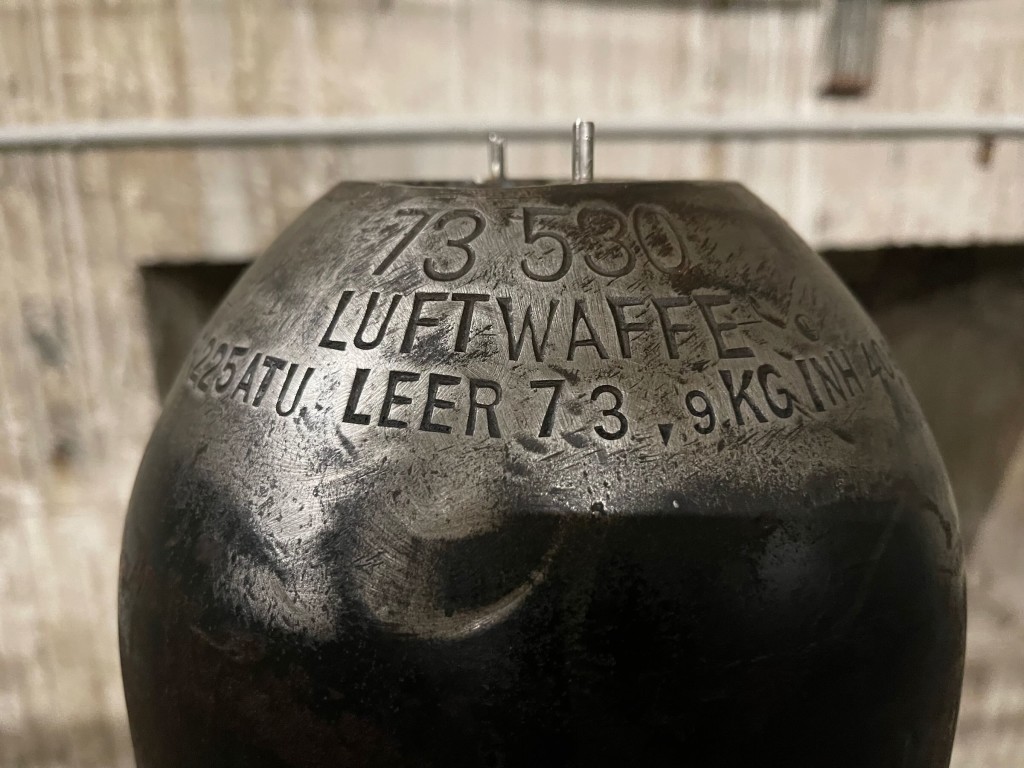

Yes, I have been working with old gas cylinders from the 1930s. I was interested in their transformation into sound-generating bodies. Their sound is like the ringing of church bells although their original purpose was completely different.

In general, I like working with metal, because this material has a unique resonating quality. Just think about the strings used to build instruments, bells or drums. It is a historical material used for all varieties of sounds. It can evoke attention as well as create art.

Also in my live acts, I am constantly searching for the uncommon. I am aiming to find sounds that are not typically used in the music industry. I record sounds from all kinds of sources. especially searching for sound qualities that are hidden within objects that are not considered instruments.

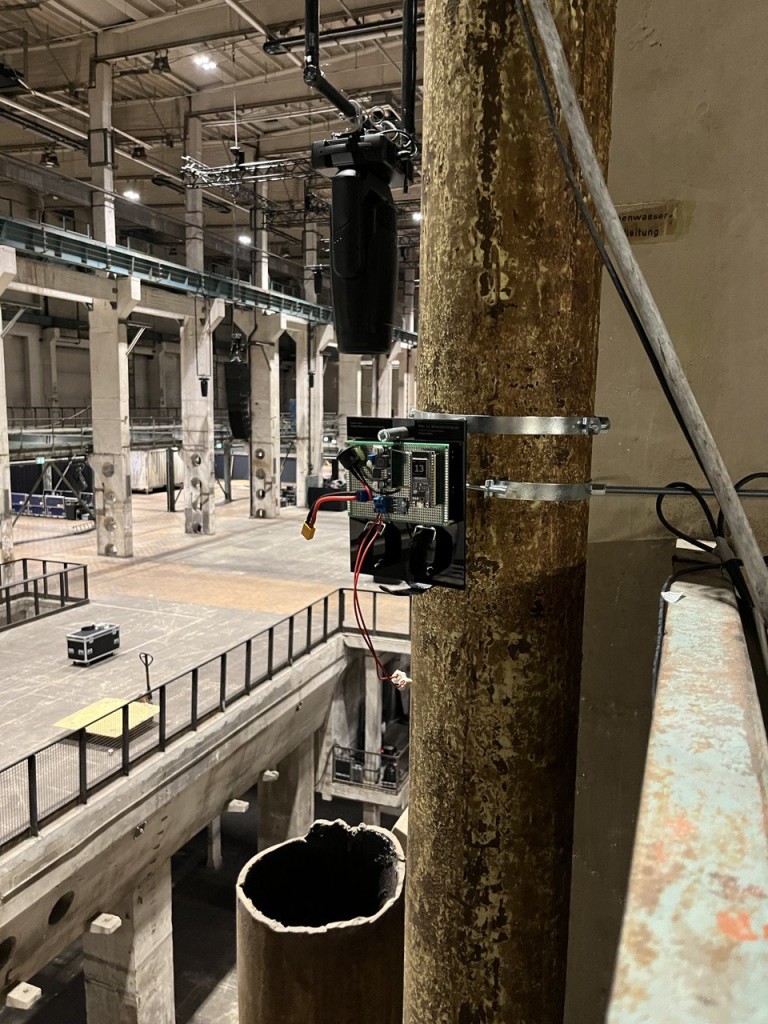

Can you describe a little about how these mechanisms work – how did you build these elements that play the physical building?

I used the ESP32 microcontroller to trigger a solenoid magnet wirelessly. Everything works with batteries and software created with Python to trigger the MIDI.

Photos courtesy the artist.

How are you thinking about patterning and how these trigger? They’re networked, so you are composing with them as a kind of ensemble?

The installation is not about creating a musical piece. It is kind of a ghost inside the machine, playing with the infrastructural elements of the Kraftwerk building and interacting with the aforementioned gas bottles. What you can explore is a generative sound, that could be rhythmical that could be asynchronous, emerging, disappearing and reappearing. It will have the qualities of a living creature – perfect and imperfect at the same time.

Photo: Anna Eskandar.

So I wondered about these gas canisters. Can you describe how you came about them and talk about their provenance?

I shared my old studio in Frankfurt with a group of environmentalists who stored a lot of old objects. There I found an old gas bottle and was experimenting with its sound. I realised it had a unique resonation quality. Then I knew I wanted to make something with that. Over time it developed into an installation project. I wanted to create a more dense experience, so I found someone in Bavaria who had a collection of old gas bottles. The bottles had been used by the German Luftwaffe during World War II and I wanted to transform those objects with their particular history into something else.

Do you have a feeling of why you chose to work with them, or what they meant to you? Or was this also an exploration of their significance to you?

There was this aesthetic and sonic interest, happening somehow intuitively. During the process of working on the cylinders. I realized that there were two levels of associations — a personal level and a generic level. I was born two days after Halabja [the 1998 chemical weapons massacre of Kurdish people] and this has influenced this work. The physical process of reworking the gas bottles can be considered a confrontation with this aspect of my past. So there is this connection to my personal history. Yet if we look at them from a larger perspective there is also the connection to our current political and economic situation. So my working on the objects was a discovery of the deeper meaning they embody and I guess this was something that subconsciously drew me to them in the beginning. But what is most important for me is the aspect of transformation of the objects, regardless of their associations. Now they became something else.

Photo: Helge Mundt.

It seems important to get the complexity of histories and identities and not something reductive. I mean, Atonal has a complex and diverse history – this power plant has lived different lives. How do you want to tell that story about yourself?

For me, memory is a resource for my work. So what I do, is an expression of my memory, the lives if lived and the identities I entail, even if the outcome takes a completely different shape. In my work, I try to avoid certain categories, like politics or migration, because I don’t like my work to be put into a certain corner and to be interpreted with a certain concept. Yet, it is impossible to avoid the fabric of your personal story and as you can see, in my current work, there is also a strong political aspect. But I aim to create something that entails more than that.

Photo: Frankie Casillo.

How does this work fit into the rest of Atonal – especially as you’ve been hanging around the space?

The exhibition is designed to create the experience of entering a living organism. It is not structured in a traditional way but more organically and I would say the experience you have when seeing my installation is fitting this concept very well.

If you enter the place there is a big concrete stairway leading you to the main floor. The first thing you will see there is the gas cylinders. They are greeting you with their presence. Creating a poetic and mysterious impression. You don’t know what they are and what their purpose is.

When my performance starts there is sound coming from different directions and the bottles will integrate sonically. It’s like an interaction between the building and the bottles. Sometimes they are echoing each other, sometimes they are just creating sound together.

Berlin Atonal runs through Sunday.

Rabon’s work:

Let’s give a listen again to some of his ambient/experimental mixing: