Grischa Lichtenberger is working with felt and stencils as well as sound. He’s speaking in hyperlinks, and misusing gear and feeding computers into other computers to form feedback loops. In short, he’s finding a unique and creative materialism in everything he does – and that means we really have to talk to him. So we sent Zuzana Friday to join in a delightfully esoteric conversation with the raster-noton artist. -Ed.

Grischa Lichtenberger is a German musician and sound and installation artist, known for his releases on raster-noton. His immersive live performances oscillate between abrasive, aggressive compositions and intricate structures of beat and melody. Recently, he has released a new triple-EP ‘Spielraum | Allgegenwart | Strahlung’ on raster-noton as a limited-edition vinyl with hand-printed sleeves. The three EPs question the connection between intimacy and the public sphere, but each of them has layers of their own meaning.

I find myself uniquely moved by Grischa Lichtenberger’s work. It’s not only the choice of sounds, their combinations and permutations, but the sense of emotion behind them that strikes me. There’s also playfulness, even cheekiness at moments. Other times, I find beauty, or anxiety, or drama, or a language we’re only learning to understand.

The music is often very physical, with the beats collapsing like detonated structures. Silence and space will swell up, stagger — carve their way to your ears. Melody in turn hastily gushes in percussive patterns, breaks down in waves, or becomes narrative. Grischa does all of this on his new triple-EP consisting of three chapters. We tried to tackle all of them in over a hour long interview.

Grischa speaks in complex, branching sentences, navigating topics and poetic descriptions in a way that mirrors his own process for bringing together his thoughts on a work, whether for a music or an installation. We talked to him about his own work and process, including the triple-EP, but also ranged to topics like Joseph Beuys.

Friday: In ‘Allgegenwart’, you write about the ubiquity of technology and feelings of guilt and a threatening sense of over-complexity. Where do you see humans and technology going?

Grischa: We like to see technology as this tool that fulfills our desires. But of course there’s more and more consciousness about us being overly immersed in the virtual world. Then we have a problem not only with communicating in real life, but also on all these social platforms. Our relationship with them has changed from the early 2000s to now. At the beginning, you had this romantic idea of being able to reach out to people you would never reach. Nowadays, the approach is more cynical and more and more people feel overwhelmed. It’s a trouble that wasn’t there before.

Plus, regarding social platforms, people are concerned about their personal data being misused.

I’d say that the totalitarian discussion of the 20s Century has shifted to the … anonymous or virtual. It’s like an invisible totality.

The first part of your trilogy is called ‘Spielraum’. In the accompanying text, you describe the Spielraum with words like hope and experiment. Do you have your Spielraum, is it your studio?

Sure, the studio is like a playground, where you have things gathered like toys. And more than that, every home is still connected to when I was little and I’d build little shelters from cushions. It’s also about intimacy and what your … private intimate space is like.

If I consider Spielraum as a space where one can be free to play around, at the same time, how do you deal with distractions? Do you turn off your phone when entering the studio?

Through desirable factors. Most of the times, I have my phone on vibration and I don’t push mail and Facebook. But there isn’t a specific preparation in the studio to shut the world out. When I started making music, I used to have internet on one PC and the music and all artworks on another PC. But then the internet became a bigger part of my daily process and it actually can even be a part of the flow. If you have a loop running and you want to let it run for a while and quickly check what’s next with Trump or whatever and go back to the music, there’s no clear boundary that needs to be there for having that flow.

The Spielraum … can address some stuff that is invisible or unspeakable. In doing art, you have a secret space to do whatever you feel like doing, a track without a snare or any silly idea. Even now, when talking about it, it seems almost impossible to defend that idea. But if you just sit there and do the track, you have the feeling that you can try things out and you don’t have to write it down and prove [it].

The sounds of the triptych are very diverse. Which devices and instruments have you used for this record? And is there a difference in terms of used instruments and processes between the three parts of the album?

Yes, there is. For ‘Spielraum’, I used a lot of “incestuous” recording methods, so to speak. I recorded from one computer to another. I recorded with a lot of feedback systems, where one program feeds into the other and also outputs to the other.

For ‘Strahlung’, I used synthesizers more excessively that I used to. I didn’t grow up with them and I don’t really know much about them. I still don’t have any hardware synthesizers, mainly because I don’t have much clue about them and I don’t have a good ear to appreciate the analog quality, even though there is a special materiality to it. But I think all synthesizers have a specific sound, and software synthesizers are still very appealing to me. Also, I once wanted to make a record that could play in the background, which always failed for me [laughs]. So with ‘Strahlung’, I wanted to make one record which I could imagine playing in the living room. And it also corresponds with the idea of the invisible force.

r-n168-2 Artwork. Courtesy the label.

From all three EPs, ‘Strahlung’ is definitely the most friendly; it has these nice melodies, for instance. Actually, the strongest impact on me was the closing track (r-n173 – 8 – 004_1115_26_lv_1_brecs) from ‘Strahlung’, probably because of the contradictory nature of its emotional and melancholic melody and abrasive, mechanical sounds piercing through. Do you remember how you made this track? What was your intention there?

I don’t remember exactly. But this track was actually meant to reconnect the listening circle of the record, its end and the beginning. So I imagined that a listener would listen to it and then start playing the first track of Spielraum again.

Apart from the digital synthesizers, what else have you used for the album — which software, for example?

I used Reason, including its Subtractor synthesizer, which is a really nice one, plus Ableton for most parts of the sequencing. I used [Celemony] Melodyne, for its nice algorithm, where you can manually slide through a polyphonic source without boundaries and divide the material in voices. Although it’s quite complex and I can’t get my head around it, it’s really fascinating.

For ‘Allgegenwart’, I used a noise suppressor. If you raise the level of a noise suppressor… you can just feed it with the background noise and it will generate a very eerie, ghostly sound, because it tries to find a tonal signal in it. It’s like a synthesizer which isn’t meant to be a synthesizer.

What are other ways for you to generate sound, do you use field recordings or sound banks?

I have an always-extending archive of sounds I use. I don’t use sound banks so much, only sometimes when I want to make a joke about a clap or something, and for instance I just use an 808 clap to have it as a symbolic reference. But normally, I like to live with sounds. I have an old track and many sounds in there, so I just put the track in the sampler, pull a bit out of there and … rework it over and over again. It’s kind of like a collage out of my own productions. I also use field recordings and synthesized sounds. I like this process where you go back to yourself and involve yourself in what you did, not only try to have the best kick drum of all times, but try to find out what the kick drum from 5 years ago means to you. Sometimes, you see ‘Oh, this is much nicer than anything I could have made up!’ and sometimes, you go, ‘what was I thinking? It’s trash!’

Photo: Sebastian Moitrot.

How do you decide which sounds will be composed together, since they range in timbre, texture, and character? How do you choose which sounds fit together in your musical universe?

It’s not accidental; I think about it very much, but I can’t tell any general method. When I have something I want to go on with, like a melody from a synth, then I listen to it and I think about what’s missing until it’s finished. Maybe it’s a bass drum – then I add it so it complements the rest, then I move on to another sound, add it and try if it all fits together.

It’s like painting for me. When you paint something new, you do it regarding what’s already in the painting. For me, the music making process is linear. Most of the time, when I do a track, I go forward, I add EQs, dynamics, plug-ins in massive chains, and I add sounds, and only in moments when I think about it and stop for a while, I can go back, re-evaluate, and correct. But in the creative flow, I tend to add and add, so the context is building itself organically and everything is connected to each other.

Your website resembles a body of work of an inventor with its precise sketches, complex descriptions, photographs and installations. Where do your ideas for installations come from?

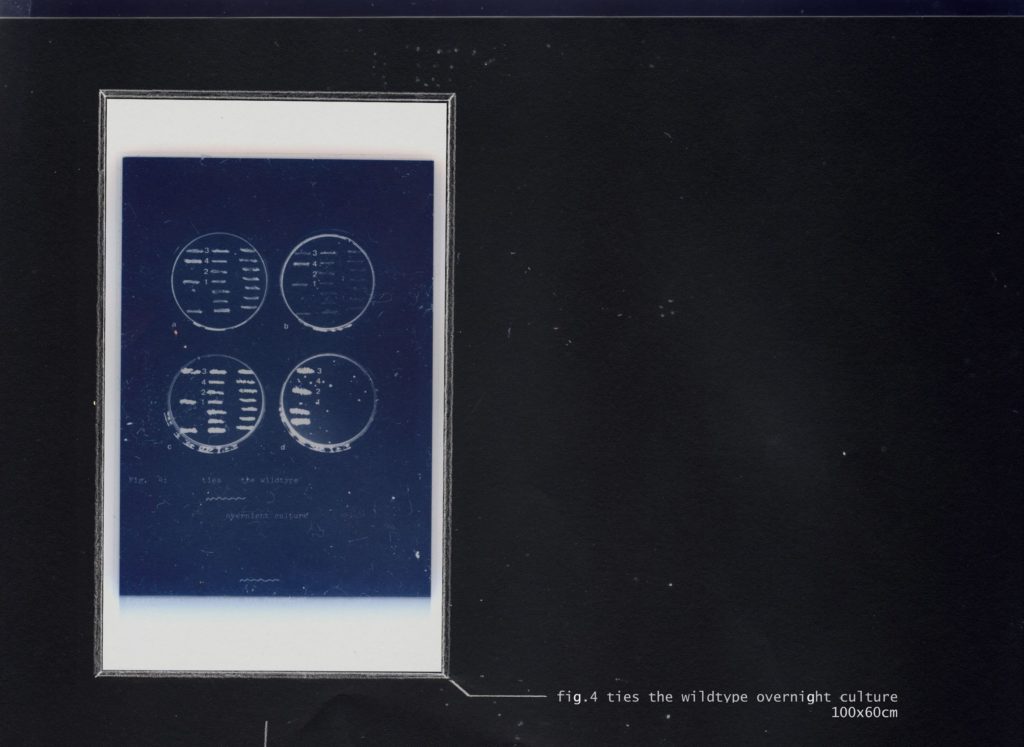

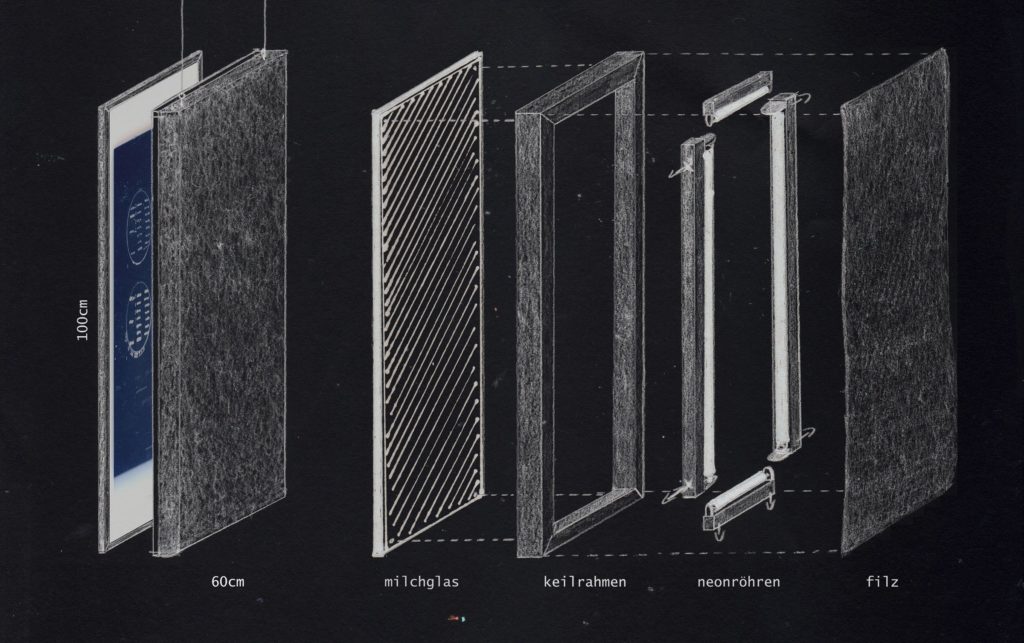

Often, there is a room or a context that’s already there. Because mostly, I am approached to contribute to an exhibition or an event. Like this year, I did an installation for a conference about genomes. So at first I try to conceptualize, which means looking into my archive and finding a drawing, painting, or a ready-made object, which fits to the general idea or a context. Then I deal with the room, like I would deal with paintings or levels in a track. Then there are strategies about materials I use – I look into the constructions I have done in the past and look for what could I use for recycling the sculptural elements. Then, if it’s a construction, I make a drawing of how it’s going to be built together. It also depends on my time and resources. The result can be an intense reaction to the room or something spontaneous.

In all my installations, there’s also a very strong reaction to works by Joseph Beuys, because my parents were his students, so I knew his work since I was a kid – I saw his piece ‘I like America and America Likes Me’ – where he imprisoned himself with a coyote in a gallery – when I was five years old. And because Beuys reached me so early in my life, I see him differently than most of the critics. It’s like music, I really liked it and felt the emotional content in there. So since I was 5, I thought ‘Doing art is really nice, you can have this sort of communication’. And when you’re so young, you still have this very present thin line of how language is built and you try to get through to people very clearly. You aren’t sure whether you understand people or whether they understand you. And you can perceive art and music like some sort of solution of this communication problem.

http://www.grischa-lichtenberger.com/installations/2015%20Genographies/

But the way I work with installations is not only homage to Beuys — it’s also a joke. Especially regarding the materials I use. For example, I use a sort of felt, which for Beuys was a mythical and poverty-stricken material. But he used a really high-quality felt. I use a material that looks the same, but it’s actually moving blankets, so they’re more industrial and cheap. I connected with this material because it was permanently laying around in my father workshop, so it’s more natural for me than felt. that felt. And besides this joke, what I also like about the material, is that it looks grey, but when you look closely, it’s actually super colorful, because it’s made of recycled plastic bags. I cling on to it, I know how it behaves, and I often use it for covering up wood constructions or making bigger spatial interventions. These things work like favorite pens or plug-ins.

You printed, stamped and signed all the 500 copies of a special edition of this triple-EP by yourself. Is this personal approach of creating a unique piece of art something you cherish?

When [raster-noton’s] Olaf [Bender] suggested to do this triple-EP and a limited edition, I was super happy, because I like vinyl and because I like having physical objects and not only a digital, ghostly trace. And I liked working on silkscreen very much, as well. I made the designs for the prints by hand and had a very nice day helping printing them. And as we layered the stencils a bit differently for each of the copies; each one is unique. It would be actually interesting to buy two of the vinyls to recognize the differences [laughs].

How would you like to push your work further in the future?

My future plan since I started with raster-noton is to find a way to [better] connect all the different aspects of art. I see that this is still a big difficulty for me, because I have all these ideas and accompanying texts. But many people despise these texts for being too long and overly complex. Of course, I have to learn how to write better, how to make music better or how to paint better, but I would also love to learn how to write better in relation to music and how to make music in relation to painting and have this all connected with one another.

It’s also important that the disciplines aren’t connected too much, because I often find refuge in one discipline when I’m sick of the other for the moment. But just for the communication, I would want different parts of my work to seem to be all more clearly coming from one particular person.

http://grischa-lichtenberger.com

Releases, artist info via raster-noton