It’s hard to imagine what the evolution of the synthesizer would have been without Leon Theremin.

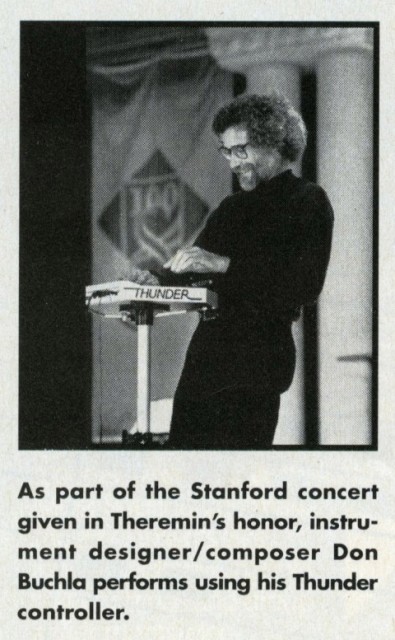

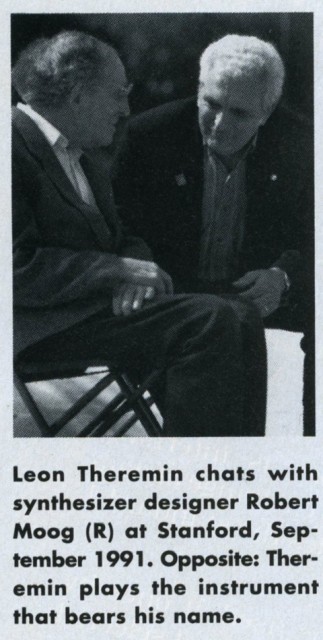

For one, it was Theremin’s invention that first captivated Robert Moog. Theremin kits were Dr. Moog’s first product and many would say, his first electronic instrumental love. That impact was significant, too, on a whole generation – actually, even my own father made building a kit Theremin one of his early experiences with electronics.

The fall of the Soviet Union still has ripples felt in the electronic music world today. And surely there’s no more poignant moment in the intertwining of post-Cold War history with musical invention as Leon Theremin’s 1991 visit to the USA – at 95 years of age.

Robert Moog wrote up that experience for Keyboard Magazine (USA), along with writer Olivia Mattis. Much of the history will be familiar, but it’s moving to read about the event.

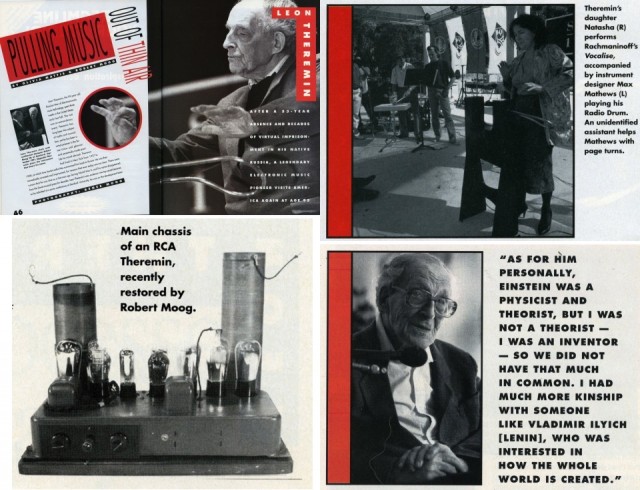

The gathering with Lev Sergeyevich Termen may have been the single greatest convergence of the 20th century’s electronic inventors ever – John Chowning (CCRMA, FM synthesis), Don Buchla, Roger Linn, Bob Moog, Tom Oberheim, Max Mathews, and Dave Smith were all there. (It’s also remarkable to think how much Chowning, Linn, Oberheim, and Smith continue to contribute as teachers and inventors today, not to mention the ongoing contributions of Moog, Buchla, and Theremin instruments.)

And of course, because of history (hello, KGB), these inventors had never really had the opportunity to meet face to face. They had “met” through their instruments. Moog and Mattis also write eloquently of ghostly guests:

For the audience, the thread of continuity and tradition linking Theremins early instruments with the world of synthesizers and MIDI is clear and strong. If you looked hard, you could almost see the spirits of Maurice Martenot, Friedrich Trautwein (inventor of the Trautonium), and Laurens Hammond joining the audience in frenzied applause.

The Thereminists were notable, too – not only daughter Natasha Termen, but Clara Rockmore, reunited with Mr. Termen. Max played with Natasha, via his “Radio Drum” – a full decade before those sorts of gestural interfaces would enter popular consciousness (via Minority Report, the Wii, Kinect, and so on).

And we get Termen, the ‘cello player turned inventor turned KGB asset, in his own words. On the reason for the instrument:

The idea first came to me right after our Revolution, at the beginning of the Bolshevik state. I wanted to invent some kind of an instrument that would not operate mechanically, as does the piano, or the cello and the violin, whose bow movements can be compared to those of a saw. I conceived of an instrument that would create sound without using any mechanical energy, like the conductor of an orchestra.

I became interested in bringing about progress in music, so that there would be more musical resources, I was not satisfied with the mechanical instruments in existence, of which there were many. They were all built using elementary principles and were not physically well done, I was interested in making a different kind of instrument. And I wanted, of course, to make an apparatus that would be controlled in space, exploiting electrical fields, and that would use little energy. Therefore I used electronic technology to create a musical instrument that would provide greater resources.

And there’s more. There’s a Theremin lesson for Lenin, with whom Termen claimed kindred interests because the Soviet leader was “interested in how the whole world is created.” And there was Albert Einstein – yes, that Albert Einstein – taking up residence in the Termen studio in order to explore visual music and synesthesia:

Einstein was interested in the connection between music and geometrical figures: not only color, but mostly triangles, hexagons, heptagons, different kinds of geometrical figures. He wanted to combine these into drawings. He asked whether he could have a laboratory in a small room in my house, where he could draw.

There are electric cellos made for Stokowski and Varese, and the tale of imprisonment (along with Tupolev) and nightmare suspicion under Stalin, the removal of electronic instruments from the Conservatory in the late 60s because electricity is only “for electrocution.” Well worth reading the piece in its entirety:

PULLING MUSIC OUT OF THIN AIR: AN INTERVIEW WITH LEON THEREMIN [Moog Legacy]

But no reason to feel overly nostalgic or lost in the shadow of history. I think what Termen says about music from space and electrical fields is just as evocative today as it was a century ago – to say nothing of an Einsteinian flatland of geometric music. In a reversal of the Yogi Berra quote “the future ain’t what it used to be,” maybe it’s even more.