Prince was way ahead of non-fungible tokens – with a symbol that was intended to make life a pain-in-the-a** for the record label. (Non-f***able totem?) And now Anil Dash and Limor Fried/Adafruit have brought back that image from a floppy.

Okay, it’s another “kids ask your parents” moment here on CDM, but yeah, there was a time in the early 90s where Prince changed his name to a symbol. (There was an associated sound, too.)

The symbol, as a combination of male and female, started as a punchline (evidently intentionally so) but came to represent the concept of non-binary in a way that only recently would be seen as acceptable in the music business. (The Brit Awards even recently scrapped male and female categories.)

That would be laudable on its own, but let’s get back to intentionally screwing with the press and Warner Bros. Jefferson Grubbs, writing for Bustle in 2016:

In the words of Rolling Stone, Prince employed this symbol “largely to mess with [Warner Bros.],” it being so difficult to reproduce. The label was forced to send out a mass mailing of floppy discs containing a whole new font for publications to use when writing about their artist. (If you don’t have the font in question, the closest you can come to typing the symbol on most computers is: O(+> .) Many people didn’t even try, simply referring to the singer as “The Artist Formerly Known As Prince” — a name that stuck. And, since TAFKAP had copyrighted the symbol as “Love Symbol #2,” the album in question became widely known as the “Love Symbol Album.”

Prince’s Symbol Meant More Than Just A Name

More detail in the narrative at this link – and, hey, it did add some great publicity, in retrospect:

In 1992, Prince signed a new contract with Warner Bros. worth approximately $100 million over six albums. But the untitled first album under the new deal, with its odd narrative storyline, suggested that things might get weird in a hurry — and they did. In June of 1993, Prince officially changed his name to an unpronounceable glyph (a combination of the male and female symbols) that entered his consciousness during meditation. There was immediate confusion, not to mention considerable derision, as to how he would be referred to in the future, prompting Warner Bros. to send out computer floppy discs of the symbol so publications could use it in print. In an apparent attempt to deflect the negative attention regarding his name change, Prince finally relented to his label’s long-standing request to put out a greatest-hits album. In October, The Hits 1 and 2 were released (the two CDs were sold separately, and together in a limited-edition three-CD set which added a disc of non-album B-sides).

When a British journalist found a solution to the name game by dubbing him the Artist Formerly Known As Prince, the moniker stuck. While it was undeniably useful, it also carried with it a certain measure of ridicule that has dogged the artist ever since. What's amazing about this period in Prince's career is how his loyal fans took the name change and other weird behavior in stride. The fanzines devoted to his music discussed such actions matter-of-factly, and sneered at the rest of the world for being too narrow-minded. Warner Bros., however, was getting frustrated with Prince for reasons that went beyond his name.

The label was reportedly after control of Prince's master tapes. Meanwhile, the artist accused Warner Bros. of stifling his creativity by not allowing him to release as much music as he wanted to. The disagreement escalated to a battle royale, and Prince protested his situation by appearing in public with the word "Slave" written on his face. He also vowed that he would not release any "new" albums through WB, and would instead fulfill his contractual obligation as "Prince" by drawing on a backlog of some five hundred songs he had recorded over the years but never released. In the summer of 1994, he released a single under his non-name on a new label imprint, NPG (distributed by the small independent label Bellmark). "The Most Beautiful Girl in the World" became a surprise hit, climbing to No. 3 on the Billboard charts, and gave the artist a bit of leverage over Warner Bros. by showing that he could deliver without the company's help. In September, Warner Bros. released Come, which was said to contain the last recordings he made as Prince, as evidenced by the years "1958-1993" on the album cover signifying Prince's birth and "death." This whole link is worth a read:

https://www.angelfire.com/wv/Royalbadness/bio.html

Parker Higgins investigated whether Prince could be honored in unicode with this symbol. (Answer – no, on three counts, as it’s personal, a logo, and protected intellectual property.)

Writing the Prince symbol in Unicode

The fun recent part of this story is that Anil Dash got one of those floppies back in 2014:

I thought maybe they just included a TIFF file, but no – as part of the performance of this symbol, it is a font, so you could type the letter P and insert the correct character. (It was also made available on CompuServe and CD-ROM.)

There was one heckuva a weird combination of formats, which I suspect is what took some help from Limor, Phil, or whomever over at Adafruit – it was a bmapfile on the Mac and some arcane format on PC too (keeping in mind TTF and PS font formats were available in 1993):

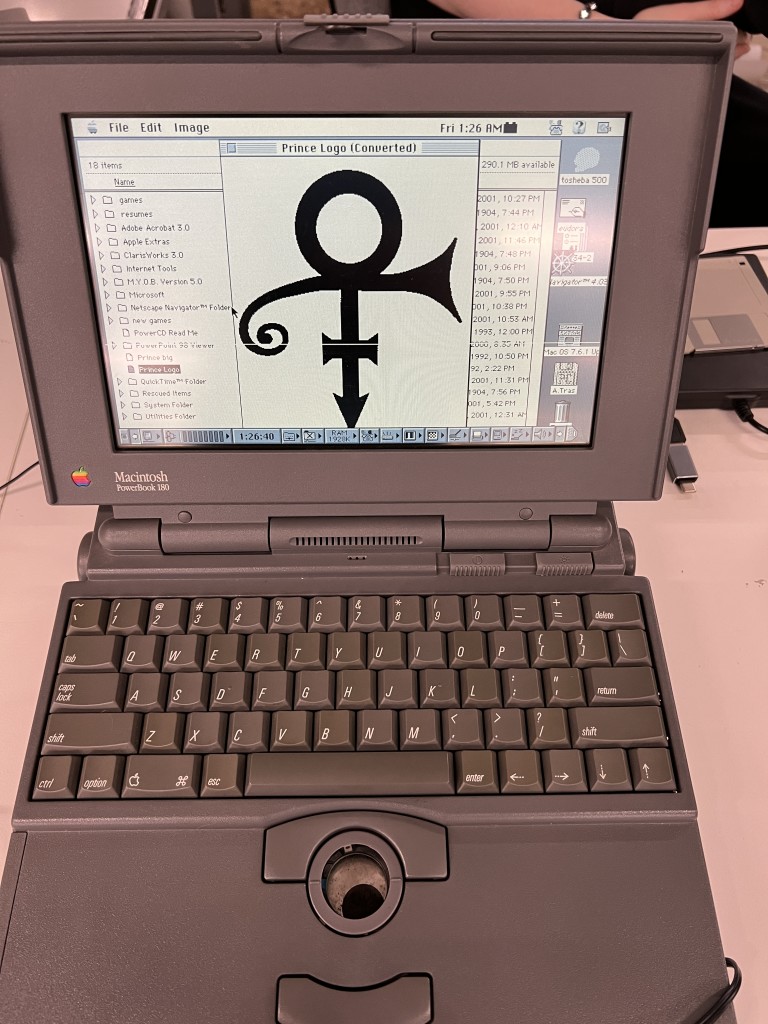

But somehow they did open the floppy and convert it on an older Mac, as pictured. Ah, memories of the PowerBook 180. (1992, the high-end model – a splurge!) This one is, uh, missing its ball.

They don’t go into more detail than that; I’m curious.

Anyway, Adafruit uploaded it on the Internet Archive – and as an image, not a font, so one of us should really save this as a TTF mapped to ‘P’, obviously.

https://archive.org/details/prince_floppy/PRINCE%20big.jpg

Via two long, long-time blog friends, so I might as well pile on this one, too:

Cracking Open The Prince Floppy After The Purple Reign [hackaday.com]

How the data was extracted from the Prince floppy disk and uploaded to the Internet archive [boing boing]

And while we’re at it, let’s listen to Susan Rogers again – because her discussion about Prince’s prolific creativity is absolutely relevant to the battle with the label: