If rock music had the Gibson Les Paul and Fender Stratocaster, hip hop and dance music have the TR-808. And if its sound seems sometimes overly familiar, even that is in some sense a hat-tip (pardon the pun) to its enduring ubiquity.

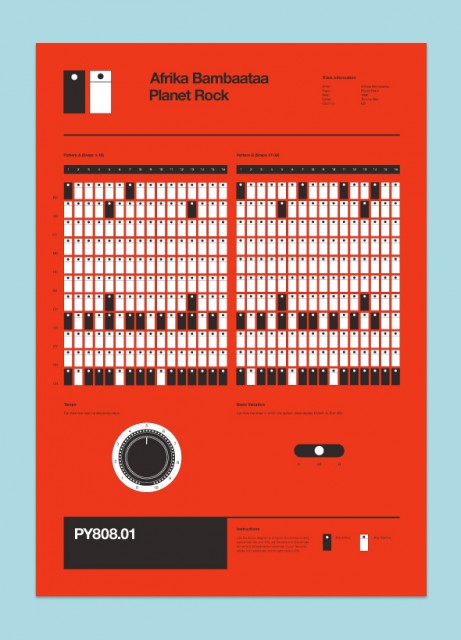

Now, the Roland TR-808 gets its own full-length documentary, told primarily through the eyes of the people who repurposed its idiosyncratic sound to spin new musical genres and start a revolution. The film features extensive input from Arthur Baker, who acts as a centerpiece for the movie. Baker was the producer behind Afrika Bambaataa’s ‘Planet Rock,’ a record that would arguably guide the long-term influence of the 808 and the course of dance music. Apart from an executive producer credit to Baker, the film is centered enough on his story that it originally even included Planet Rock in the title.

We knew a large-scale 808 documentary was coming, but now, at last, you can see it – if you’re in Texas this month, that is. Multiple screenings around Austin during South by Southwest will mean residents and visiting hipsters will get some chances to pack theaters. No word yet on when it will tour, but early press indications and demand suggest this could see a wide release. (CDM isn’t at SxSW this year, so let us know if you see it; we’d love to hear your review!)

The film is the work of newcomer director Alexander Dunn and a small UK house called You Know Films.

There are some notable points on the way the film has gone.

For design nerds, the graphic identity and poster come from designer Rob Ricketts. His iconic, beautiful graphics are interwoven with the movie; you’ll remember his beautiful 808 programming posters. See his take on “Planet Rock” here.

You do get the story of the TR-808’s original design and engineering. Roland founder Ikutaro “Mr. K” Kakehashi, recently seen accepting a technical grammy for MIDI alongside Dave Smith, talks about the machine’s origins.

But most significantly, the 808 film’s big draw and marketing focus are on a lineup of music stars. That includes early pioneers behind its sound, but also EDM headliners – and yes, Phil Collins, as a kind of foil, an actual drummer who becomes fascinated with this machine. That has led to some early complaints about the appearance of highly-paid but widely-despised French superstar DJ David Guetta.

Rather than join in on the hate there, let’s step back for a second. Modern techno, house, EDM, or whatever dance genre you’d like to choose is heavily indebted to these earlier musical creations. The success of someone like Guetta, complete with global revenue that might make a medium-sized fast food franchise jealous, is revealing of just how far that influence would eventually spread. There’s no reason, then, not to speak to people like that in this kind of documentary, alongside the pioneers.

And it should all be a reminder of why these early pioneers were so significant – because there was absolutely no guarantee that history would work out this way. By the 80s, those aforementioned Fender and Gibson instruments were already well-established, and had a history all their own. But something like the TR-808 seemed destined to be forgotten. It’s incredibly easy to imagine an alternate history where the 808 joins the many other failed groove boxes that litter music technology history.

In fact, the 808 wasn’t discontinued coincidentally: the box was in fact something of a failure. And anyone who finds the sound of an 808 grating now must surely be slightly gratified by the early Keyboard review that famously compared it to “marching anteaters” (a phrase more appealing than anything dreamt up by Roland marketing).

It was these artists who gave those sounds their permanence. Lately, European dance music has gotten tangled again in the tired debate over who originated techno. It’s a tired argument to me, because it seems blatantly obvious that both German industrial music and African-American and generally American music deserve tremendous amounts of credit, each a radical departure from what might have been. You might as well ask whether cheese or ground beef deserve credit for the cheeseburger. And as America’s race and income inequalities become still more pronounced, now seems an ideal time to pour as much energy into talking about all those historical origins.

These early producers and their records are the reason any of us are around having these conversations today. Consider that hip-hop artists can be easily credited with the historical impact of both the 808 and Roger Linn’s MPC (the LM-1 having been mostly doomed to the dustbin).

Arthur Baker is a perfect example, and that history is all immediate and audible on the record itself. You can’t have this sound without the work of Japanese engineers. You can’t have the groove without Germany’s Kraftwerk. But you also can’t have it without George Clinton, without Philly soul, and the Afro-American music Baker grew up with. The fact that electronic music has feet in the dynamic recent evolution of both Germany and America (and the UK, and so on) is part of why its history is so relevant.

Here’s Arthur Baker on the 808 and his musical quest, from while this documentary was still in process.

And this is why history as told through music is such a beautiful thing. One record can lie at the intersection of the Great Migration of African-Americans north, of the legacy of slavery and the impact of the Second World War and Cold War on Germany, Japan, and beyond. It’s machinery and technology as mixed up with parties and culture. Asking who invented what is often missing the point, because what happens after invention is essential.

I don’t think we can ever have too much of this history, particularly because that history is alive and continues to unfold and melt.

Evidently not included in the 808 film, for instance, is Amos Larkins and Miami Bass. There’s always more to tell.

But that makes me look forward to this movie.

Executive producer Alex Noyer talked to Billboard about the movie – and the fact that the actual physical machine had less impact than the samples:

The physical machine appeared and disappeared quickly, but its sound stuck. It’s been used repeatedly, religiously, for decades. The misconception comes from the fact that a lot of producers have never actually used an 808, they’ve used samples. And really, the disappearance of the 808 is still an open topic in people’s minds: Why was it pulled from the market so quickly? What other factors were involved? We get into that in the film.

SXSW Preview: New Film Looks at the 808 Drum Machine — ‘The Rock Guitar of Hip-Hop’

For more:

Here are Roland engineers on the 808 in advance of the AIRA TR-8 announcement – and why the original was intended as a backing track generator, not a “lead instrument”:

BBC Radio 1 on three Roland machines (303, 808, 909):

A short documentary on the 303 (because what are drums without bass, after all?):

Press release on the film [lots more details there]

Documentary mini-site with mailing list (to keep up on screenings):

And – the track. This to me is the sound of growing up in the 80s, the sound of hip hop, the sound of techno, as made by these artists with this machine. It’s … still kind of amazing: