You’ve probably used Shazam. If you’re a dance music fan, you’ve probably even both used Shazam to get a track ID at a club and cursed someone else for using Shazam to get a track ID at a club.

What surprisingly few people know, though, is that Shazam has desktop clients as well as the phone apps. And unlike the phone apps, these apps will lurk in the background listening to everything on your computer’s mic, and pops up a notification when it “hears” something it recognizes. This is presumably useful at those times you’ve sat at a coffee shop and thought to yourself, “wow, I wish I knew who that annoying artist was so I could avoid him/her/them in future and never have to hear them again.”

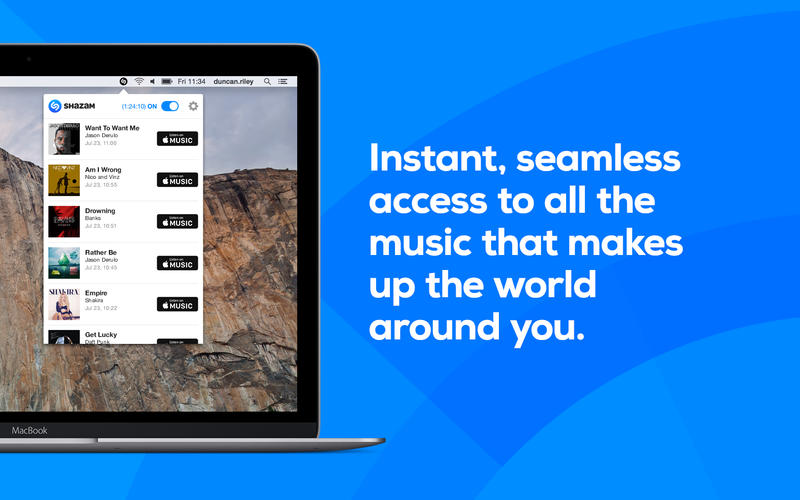

The apps are available for Mac and Windows on the Mac App Store and Windows App Store. The Mac app sits in your menu bar; the Windows app is a widget.

Here’s a funny thing about the Shazam app, though. It’s listening in the background all the time.

So, try this experiment: install the app, then leave it around while you’re producing music. (Your Internet connection will need to be active, of course.)

An amazing thing happens: Shazam starts to hear things it thinks are actual songs, when they aren’t. As near as I can figure, it’s confused by the dominance of drum machines like the 808 and 909.

The mismatches themselves, though, can be fascinating. I’ve watched with my own music. Now, first, of course it gets the bpm right, and of course there’s some common element, though even that (beyond an 808 kick) is tough to find. I also find that the false matches don’t happen when I’d expect – using preset sounds and unaltered 808s, for instance – but at rather unexpected times, when the rhythm is identifiable but the timbre isn’t. It is clear it knows it’s hearing four of … something … on the floor, and gets muddled from there.

As with other algorithmic “intelligence,” though, it doesn’t make mistakes in the way we make mistakes. So sometimes I’m playing some experimental techno and I get … massive, horrible EDM, stuff that doesn’t sound anything like what I’m playing. (In some cases, it seems poor production quality in the matched track – like overly aggressive compression – is actually what confused the algorithm.) In others, I get just random matches that happened to feature a bass drum – hello, arbitrary tech house.

A resonant filter plug-in made it find this… whatever this is. No idea, but this cool. Key clearly matters, and beyond that, particular intervals inside a key seemed to match (which explains a lot of what’s going on here).

That alone would make for entertainment value, but some of the matches are actually interesting – and relevant. So about a fifth of the time, Shazam algorithmically finds music that’s stylistically related to my own, in ways that humans might never have guessed. And that’s where there’s obvious potential for the future, though the algorithms will need to get smarter (and look for relations rather than just matches, which is a whole different ball game).

For example, I’ve never heard this track “Over Smog” by Irregular Synth. (Great act name, by the way.) The track I was working on in that session doesn’t really sound like it, in that you wouldn’t think one was plagiarizing the other. But Shazam did pick up on a rhythmic motive that was the same length in both. And as a result, I really like this track. Heh, now I’ll have to put them on a mix together when I finish mine.

Oh, and this was great – it found this totally unrelated pop song because I think I was using a Scala file on a synth with the same tuning. Cool.

So, now I think I’ll start playing all my productions for Shazam – and maybe even some of the stems – to see what it thinks. Shazam’s matches are doubly interesting, too, because the statistics will tell you not just how popular a particular song might be but how many people were hearing it and saying “I want to know what that is.”

All of this means that the world of algorithms might not be as cold and predictable as we think. Depending on how we humans apply the algorithms, we might get results that combine human and machine logic in totally unexpected ways – that expand possibility rather than constrict them.

Or, at the very least, you have a new toy in the studio. And the party crowd assembled by algorithm is going to be really … interesting.