Gamma, the oversized electronic music and contemporary art event, has just wrapped in St. Petersburg, RU. We talk to Moscow-based curator Natalia Fuchs about transformations both historical and future in the realm of intermedia art and technology culture.

The world scene is starting to catch on that Gamma, held in impossibly sci-fi post-industrial setting, is a cultural firestarter. This year’s edition was both Gamma Festival and the Gamma_PRO conference. Gamma Festival is a massive packed weekend treading lines between club and experimental culture, digital art and techno, sometimes all at once, with diverse headliners like DVS1, Codex Empire, Cio D’or, Robert Lippok [Raster], ORPHX, Mike Parker, and then a rich lineup of artists from Russia’s own m_division and Arma17 collectives. Gamma_PRO had its own lineup of live acts – Hauschka, Deadbeat, Loscil, and others – but simultaneously gathered professional festival and curation programming including a first-time Russian collaboration with audiovisual festival giant MUTEK.

Here’s a taste of what it was like from the aftermovie:

Here, we get to talk to Gamma_PRO’s Natalia Fuchs, not only about Gamma, but about how Russia fits into the larger scene, and how its own audiovisual community is maturing and making connections outside the country. That in turn I think reveals a lot about how the global tribe of digital artists relate to one another and ever changing technological and societal change – particularly looking at this moment as we reach a generation’s distance from the fall of the USSR.

And if you only follow the geopolitical headlines, you might well miss cultural movements underway internationally, including how Russian artists can fit into that global scene. And in turn, it’s equally relevant to understand how Soviet-era artists communicated and shared ideas across the so-called Iron Curtain in decades past. Better understanding that work can also mean deeper, more technologically sophisticated, more advanced and relevant work now. (Those who fail to learn from history are doomed to make crappy uninformed media art, in other words, to warp the popular cliche.)

We’ve previously covered my own interest in that area, which I owe to an ongoing collaboration with Natalia:

Enter the trippy, fanciful world of Soviet light art studio Prometheus

So, what does this mean as an international curator based in Moscow (and working on projects far afield with partners like the Barbican in London or MUTEK in Montreal? And what has techno got to do with any of this? Let’s go deep into all those questions.

Peter: First, can you give us a little bit of your trajectory as a curator? What was your path to Gamma Festival, and what are your current projects?

Natalia: I work in the intersection of art and technology in Russia since 2002, since I graduated from my university and became a communications specialist in the field of culture for several international commercial brands. I was doing integrations in culture marketing for companies like IBM, Microsoft, Daimler Chrysler, Pioneer DJ, Fujitsu, and many others. Of course, that all was related to understanding what kind of upscale innovation you integrate with, and at some point I realized I am deep into art and technology in a way that requires an art degree and a complete change of professional approach. I felt that I could contribute a lot to the local artistic communities in Russia bringing together innovation, culture, and international connections; that’s why I moved for some years to Austria, where I got my degree in Media Art Histories, and was back to Moscow to circulate as new media researcher and international curator.

During my last five years in Russia, I was the founder and curator of the interdisciplinary program Polytech.Science.Art and international exhibitions including Ars Electronica co-productions at the Polytechnic Museum; then curator and deputy director at the National Center for Contemporary Arts, where I launched a platform for innovative art and technology. Since 2018, I’ve develop my own art practice – ARTYPICAL – being part of many international projects (such as with ZKM in Germany or Barbican in the UK) with my expertise in art and technology, and also emphasizing Post-Soviet states. Gamma Festival is one of the largest projects to which I contribute in Russia at the moment. It’s operated by m_division agency with absolutely fantastic production team.

How are you working with m_division to make this project come together? How did this particular program come together for this summer in St. Petersburg, combining all those different actors, international curators, musicians and artists?

We are partners with m_division to develop Gamma Festival in Saint Petersburg, and my art-practice is actually providing international focus to the Gamma_pro forum, special professional program launched this year. It was very successful from the very beginning. We got an amazing location for that – the legendary old Soviet film pavilion of Lenfilm studio – and we managed to have [Montreal-based] MUTEK as a featured festival for the AV showcase in the frame of Gamma_pro. We had speakers from Today’s Art, CTM Festival, V&A Museum, MOTA Museum, and many others. That was hard work and a great start, and I had never seen such a level of synergy of institutional, festival, artistic, commercial and non-commercial, independent entities in Russia before — that’s very honestly from my side. We have some plans for the future, especially in regards to an art program extension, and it all looks exciting. I personally would love to create a sustainable infrastructure for art communities behind Gamma Festival, and I’m happy to know that producers of the project are willing to support it with all the resources available.

St. Petersburg, setting for GAMMA.

St. Petersburg.

There’s of course a massive number of different artists, institutions, covering science and art, culture… how would you describe this larger picture? Is part of the idea to make this a bit blurry, to put everyone together and see what happens, both across the Russian and international scene? What do you hope they leave with?

I think Russia has a wrong image in terms of cultural policies: we are seen as very much a rigid and framed world. With Gamma Festival and basically with all the activities I run in Russia, I always try to make it clear that we’re part of the global community. And art and technology is that exact intersection that gives us an opportunity to be connected despite global politics and issues. This is the way it actually existed even in the time of Iron Curtain – scientific advantages were spread in the professional communities, and we all were mentally attached to each other and kept a complex, in-depth exchange going. Now, researchers see that when digging deep into media archeologies, for instance. So I would love people to leave Russia and our festival with the feeling that we stay connected; and we are very much alike. I am in a way doing independent cultural policy for world peace using art and technology as a tool now.

There’s this notion of a creative class fueling Gamma, as with other international hubs – how would you relate that creative community in Russia to this sort of international tribe of artists? Do they retain their own culture? And, for that matter, is this a class that can expand, that other people can enter? (I suppose our own personal experience may be about bringing others into that tribe, via education and networking?)

Well, for some safety reasons, and in order to ensure sustainability and growth, we had to stay in the 1990s and early 2000s away from all official connections and wide contacts to the traditional art world in Russia. The research we did expanding the relationship to the international tribe of artists required full independence for a long time. I actually didn’t make any step to governmental relations before I was 100% aligned and rooted in the international community first. Therefore, I traveled, studied, and worked abroad; I was very much West-oriented all my life. But I’ve seen all the young people here who are desperate to even average contemporaneity, and I felt myself obliged to develop cultural relationships back in Russia at some point.

I still feel weird sometimes, when I reestablish myself as a core of the current Russian art and technology movement – and Gamma is one of the boiling points at the moment, but not any other project initiated by the local authorities. At the same time, I see that this is something you can easily cut and have preserved just as a historical notion. Education and networking are important for making international connections; but I have to underline that in Russia, in that tribe you point out, we are still suspicious of anything that comes out of the government. So as everywhere in the world, you have to start with building trust; and if you don’t have proper mediator for those connections, you can’t develop it. So I keep myself always diversified, even when I had important institutional roles in my country. And I give this advice to every young artist, musician, and curator in Russia.

Moscow and St. Petersburg have both I know been scenes of real change culturally – friends I know who grew up there even say they’re surprised by differences even from just a few years ago. For people who perhaps don’t know these cities so well, how would you characterize those changes? Are there things you can feel personally in the work you’ve touched in your various roles? What about the rest of the country – Kazan [Tatarstan] I got to see was really growing, too; is there a way for other parts of the country to have the access to that culture, as well?

I think that we live at the moment when all the efforts of my generation (mid 30s) finally came to fruitful results in Russia. You maybe don’t see it from the global politics strategies, but you see it when you come to the country and visit two capitals of Russia – Moscow as business capital and St Petersburg as cultural capital. I can’t imagine any progress if you are not related to the both scenes – it’s very natural for the creative class to work and essentially live in two cities at once. Just a few years ago, we were in the state when we were still young and couldn’t deliver our messages in a mature style. Now that has changed dramatically; when you come to Gamma in St. Petersburg and enjoy the afterhours, you hardly feel a difference from Atonal in Berlin. Maybe the lack of an international crowd is still there, but we work on making our world open despite all the political issues. We speak the same language of art and music here; and people who are in charge of all the changes here in cultural life are internationally experienced. And if to speak about the other cities in Russia, surely our culture is expanding – only this year I am having talks, lectures, and exhibitions on the future of art in Vyksa (close to Nizhny Novgorod); Krasnodar (south of Russia, Black Sea); Vladivostok (Far East); and Kazan that you mentioned is developing a Light and Sound Museum project involving again many experts of the global media art community. So it’s definitely growing and changing in a positive way.

Is there something unique about Russian history that it seems there is this interest in cross-media work so early?

Of course, this all comes back to the early XXs century when Russian futurist artists have chosen cross-media language in performative practice, particularly as the visual language of a new generation — not to mirror Western European traditions, but to develop our own avant-garde traditions. Russia also has machines and social capacities to stand on the same platform with the European offshoot of futurism. Russian futurists that developed Marinetti’s ideas locally were the forerunners of modern artistic strategies – that is, the skills not only to create talented works, but also to find the most successful ways to attract the attention of the public, collectors, and patrons.

And despite the seeming closeness of Russian and European futurists, history, traditions, and mentality gave each of the national movements its own characteristics. One of the signs of Russian Futurism was the perception of all kinds of styles and trends in art as one, so that was the rise of interdisciplinarity that was so important as an approach for cross-media art. “Vsechestvo” (the art of take it all) became one of the most important futuristic artistic principles in Russia as early as in the 1920s, and we are still following it in the contemporary new media art practices. [Vsechestvo or as some art historians translate it “everythingness” was coined by Georgian-born artist and Russian futurist – and Dadaist – Ilia Zdanevich.]

You’ve worked both as an historian and a curator. And we’ve gotten to work on this connection between history and the future. A lot of the digital media scene globally is called upon to show work that gives the impression of being new, flashy, of course – but how might the past as understood through media archaeology and history inform new work?

Oh yes, that’s my favorite question! When you are an art historian, you hardly see anything new – that’s the problem. I make many artists disappointed, not only happily showing them their place in the world art history. 🙂 But at the same time, I think that’s great that media art history currently is developing as a science, so media art historians can follow scientific and technological progress as well and make innovation in the arts visible. I see the media-archaeological approach actually as the only possible way now if you want to make a real progress in the arts. And this approach could build the relation to art and technology communities in the past where so much is undiscovered yet. We both know Prometheus’s story about innovative art that was related to the global art and technology communities in the 1960s in the Soviet Union, as well – such examples are very important to present to the world, to give an understanding of our long-lasting existing connection to deep levels of creative research.

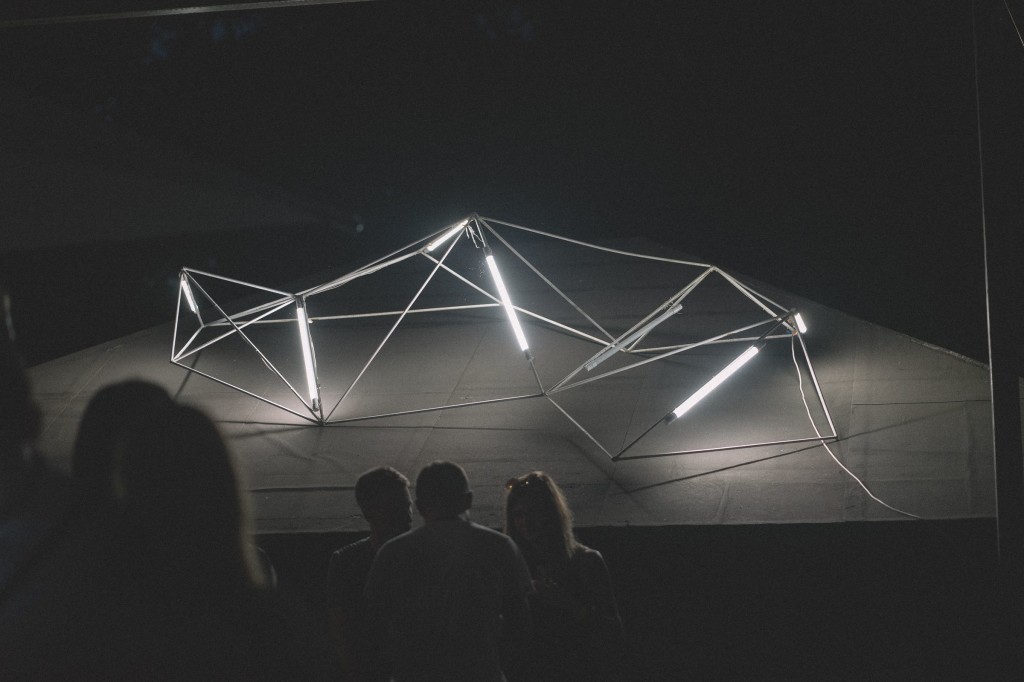

Gamma 2018 at full tilt.

You of course have an extensive resume in curation, and people can find that. What they may not know about you is that you’ve also got this strong connection to techno and this electronic music party culture. Where was that first experience for you, when you were younger?

Techno music was something I was always involved in. In the early 1990s, rave and contemporary art coming from abroad was the only thing you dreamed of if you wanted a breath of fresh air. I was involved in party organization and club activities since I was in high school in Russia, and when I staged the first performance, I was only 16 years old. I was given at that time the role of curator in our club promo-team together with my friend. I mean that was quite naive in 1996 and so on, but that was an experience you could go with further at that time – I was quickly integrated to many international club culture communities (in the Czech Republic, in the Netherlands, in Germany), and electronic music party culture was always a red line I had in my life doing everything from booking and developing yoing artists (I was a booker or maintained art relations for Vakula, SCSI-9, and Dasha Rush in different periods of my life), organizing parties, from streaming techno-radios to participating in festival organization.

I see electronic music and techno music as something that formed me as a curator, as well. I even couldn’t stop myself from organizing the first techno parties in Moscow’s museums and making it a trend – you performed at the Polytechnic Museum in 2015; Gunnar Haslam played at the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art the same year by my invitation. When you just love techno, it definitely gives you a touch not many people can easily have, shaping you as cutting-edge at all times and especially at a time of innovation and the rise of technological culture.

Any medium I think can be accused of repetition, but it does seem digital media as can sometimes be in danger of becoming frozen in the past in terms of aesthetics and concept. Is there a need for media artists or reinvent these media; is that fair? Alternatively, what work would you say does feel genuinely contemporary — in aesthetics, in concept, and/or in relation to the latest technology?

I keep those thoughts a bit for myself only at the moment – it’s a bit scary to share what I really think of the new aesthetics. But I’d say everything has a potential for transformation. Immersion is the term that was taking over the digital art world in the last centuries; now I believe in the age of artificial intelligence. Now art and technology experiences will extend human perception; they will create space for human transformation. Bioart, prosthetics, and so on may allow you to gain new experience, to perhaps change your physical presence and even personality.

So contemporaneity for me is in active transformation at the moment; physical, psychological, emotional, bone-deep experience. One of the last artworks I experienced this way was amazing post-digital piece by the Chinese artist Lu Yang “Delusional Crime and Punishment.” [See an article on that work, as well as a reference from NYU Shanghai.]

AI and machine learning are a big buzz-worthy topic; we started this year at CTM with this thread in our hacklab program and it’s something I know many artists are pondering or responding to directly. What can you tell us about your advisory role with the Barbican; how are you working with them, or anything you can share from that program?

For me, this project is not just an exhibition, but again a way to participate in the development of cultural policies (and technological culture in particular). The main idea behind the project of the Artificial Intelligence exhibition at the Barbican Centre in London where I work as Advisor now is to smooth the attitudes existing in the society towards artificial intelligence and give to the audience a deeper understanding of the history of cybernetics and AI research. The project will tell the story not of only one part of the world, but will create global vision on the topic. It will be ready by next summer and will travel worldwide. So I am very much excited about that. I think that’s the big step to changing perception – destroying AI myths in pop-culture – and artists could contribute here best of all.

Right now in Berlin, there are “what is culture for?” posters hanging everywhere. What role do you think cultural ambassadorship can have? Is there a way to make it more relevant to the rest of our societies?

Culture is here to shape the meanings. Without it, we hardly could exist and evolve, I guess. And cultural ambassadors are first of all very attentive and brave people – that’s hard work to observe, get the essentials and communicate the meaning to the rest of the world. You have to expect to be criticized and misunderstood, but have to stay stable and persistent. To the rest of our societies, that basically means that culture has still to be mediated. Especially synthetic practices as what we are into – music, art, electronics, science, atypical connections between the contraries. When we make understanding of complexities easier to the people that don’t have resources (could be just mental) to dedicate their life to art and culture production, we make a step forward, I guess.

I feel my relation with the rest of the societies as the periods of comfortable coexistence, replaceable with stealthiness for each other. And this invisibility for me means a research stage – when I am deep into the creative process and thinking what important meaning to represent next to the society around me. That’s a significant concentration of time and internal forces, actually, so we will make cultural ambassadorship relevant when we will start clearly communicate what our life actually is.